Egham Races

Charlotte Young, PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London, investigates Egham during the Early Modern period and in this article, looks at Egham Races.

Horse racing as a pastime had existed in Britain since the Roman period but its popularity was greatly increased in the 17th century. James I established the tradition of horse racing in Newmarket, and the sport flourished during the reign of his grandson, Charles II.

The first established races in Egham took place in 1734. They became an annual event, initially held in September but later moved to August. An advertisement for it appeared in the London Evening Post on 22nd August, stating that the races would be held over a three day period, from Tuesday 24th to Thursday 26th September. The prize for the first day’s winner would be £20, the second day £10 and the third day £5. Horses would run on different days according to their strength and size. Any racers intending to enter their horses for the £20 or £10 races were instructed to sign up at the Red Lion in Egham on 10th September between 9am and 6pm, after which the horses would be taken and held at a safe location until their respective races. It would cost 2 guineas to enter the £20 race, and 1 guinea for the £10. The organisers requested a minimum of 3 horses for each race.

The event turned out to be highly successful. The London Evening Post followed up its advertisement by printing 2 reports, one on the 24th and one on the 26th. The first report stated that three grey horses had been entered for the £20 race; one belonging to the Earl of Portmore, one belonging to Mr Warren, and a third whose owner was not named. Lord Portmore’s appearance is interesting; he was Charles ‘Beau’ Colyear, a former MP and noted racehorse owner, who was later a founding Governor of the Foundling Hospital. The odds were 3-1 against Lord Portmore, but ‘he won the two Heats with great Ease.’ The reporter also noted that ‘There was a great Appearance of good Company’. The brief report printed on the 26th stated that 4 horses had been entered for the £10 race, and that the winner was Mr Child.

On 9th August 1735 the London Evening Post featured another advertisement for the races, which would be held between Tuesday 9th and Thursday 11th September that year, again at Egham Meadow. The riders were told to present themselves and their horses at the Red Lion on 2nd September between 10am and 4pm. The cost of entering the races and the financial prizes had also changed; the first race was worth £25, and would cost a guinea and a half to enter; the second race was worth £15 and would cost 1 guinea, and the third race was worth £10 and would cost 15 shillings.

The General Evening Post of 13th September contained reports about all three races. The £25 race contained six horses, and three heats took place. Two were won by Mr Bradly’s chestnut mare, and one by Mr Knell’s chestnut stone-horse. The £15 race featured 7 Galloway horses, and the winner was ‘Mr Croft’s bald Galloway, Merry Andrew.’ The £10 race only contained 2 horses; a mare belonging to the rat-catcher, and a mare called Molly Mog; the race ‘was won with a great deal of Ease by the latter.’

Advertisements for the Egham races would be printed in multiple editions of the London Evening Post in the weeks leading up to the race to ensure maximum publicity. As the event gained popularity, the advertisements began appearing in the Post earlier and earlier. For example, in 1734 the race on 24th September was advertised in late August. However, in 1737, when the race was scheduled for 1st September, the advertisements began appearing in June. By 1739 the advertisements began in May.

By 1770 the event continued to grow in popularity, and the advertisements reflect this. They were placed in more newspapers – the Public Advertiser, Lloyd’s Evening Post and the London Evening Post in August and early September – and were much longer and more detailed than those of the 1730s.

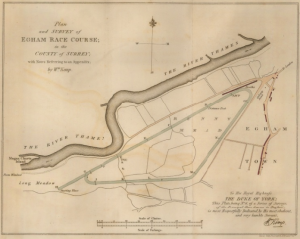

The races still took place over three days – this year the 13th, 14th and 15th September – but the event had greatly expanded. A major change was that the location of the races had been changed from Egham Meadow to Runnymede. The financial prizes for the three races had been replaced by sponsored prizes of plate, each worth £50; the Noblemen and Gentlemen’s Subscription Plate, the Town Plate, and the Ladies Plate. The 19th century addition of the King John Plate and Magna Charta Plate to these prizes were a suitable acknowledgement that the races were being held at such a significant landmark.

The winner of the first 1770 race would be the best of three 2-mile heats, and the second and third races the best of three 4-mile heats. The horses needed to be presented at the Red Lion as usual, between 2 and 7 on Saturday 8th September. The organisation of this registration had clearly been improved, because the owners now had to agree ‘to be governed by such Articles that shall then and there be produced’, which suggests that a written contract was being enforced. They also had to ‘produce a Certificate of the Horse’s Age and Qualifications’, as well as pay 3 guineas and 5 shillings as a registration fee. Suggesting that foul play had taken place in previous years, the advertisement clearly forbade horses being hired for the races, and interestingly horses belonging to ‘Mr Castle or his son, or Mr Quick’ were banned entirely, as was Mr Castle’s jockey Thomas Dunn.

Other entertainments had also been added to the schedule. Cock fighting took place at 11 o’clock each morning at the Red Lion between the gentlemen of Middlesex and the gentlemen of Surrey. Booths were also set up at the race track, presumably offering refreshments, but the owners had to be inhabitants of either Egham or Staines. A double booth cost 2 guineas, and a single booth 1 guinea. In addition to this, a tradition had been started of holding a ball on either the first or second evening of the races. The 1770 ball was held on Friday 14th at the Red Lion.

A clear demonstration that Egham races had grown in popularity is the fact that there was a coach service running from the City of London to the racetrack. The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser ran an advertisement on Monday 10th September telling spectators that,

‘A coach and four horses sets out from the New Inn, in the Old-Bailey, to Egham races, every morning at eight o’clock.’

However, in 1773 events occurred which reminded the spectators that racing could be a dangerous sport. The General Evening Post ran its usual account of the races, summarising the winners, along with this unfortunate tale of a man from Windsor who was trampled by a horse ridden by an inn-keeper from Staines;

‘On Tuesday evening, at the time the horses were running for the last heat, a terrible accident happened: a poor fellow on foot running among the horsemen, who were crowding in to hear who was the winner, was thrown down, and taken up for dead, but lived till four o’clock on Wednesday, and then died in the greatest agonies; the man and horse were likewise thrown down, and the rider broke his collar bone. The man who died lived at Windsor, and worked several years with Mr Coombes of that place; the other unfortunate man keeps a public-house at Staines.’

Another trampling took place in 1778, when the Public Advertiser reported that ‘a young lad was beat down by one of the horses’, but fortunately he wasn’t badly hurt.

This was not the only danger, however. Race-goers would often be carrying money with them to place bets, which made them easy targets for robbers, as his article from the St James’s Chronicle in 1775 demonstrates;

‘On Wednesday Night about Eight o’Clock as Mr Stacey, Master of the Bedford Arms, Covent Garden, and his Wife, were returning from Egham Races, they were stopped by two Footpads near the back Front of Holland House, who robbed them of their Watches and Money.’

‘Footpad’ was a term for a common thief who targeted pedestrian victims.

In spite of these risks Egham races continued to grow in popularity, and by the 1780s they were attracting royalty. King George III and Queen Charlotte were prevented from attending in 1786 due to strong wind, but their sons the Prince of Wales and Duke of York were there the following year. Their presence apparently caused quite a stir, and The Times reported that,

‘Their Royal Highnesses the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York were at Egham races on Wednesday; when a greater concourse of the Nobility and Gentry was also on the race-ground, than perhaps was ever remembered on a like occasion. The sport was excellent.’

The Prince of Wales seems to have particularly enjoyed the event, as his presence is also noted in newspaper reports from 1789, 1790 and 1791. This royal patronage, which continued well into the 19th century, had an extremely positive effect on the races, which were transformed into a fashionable society event, a place for members of the court to see and be seen. On 26th August 1808 The Times reported that,

‘Her Majesty and the Princesses have been highly entertained at Egham Races, where the Dukes of York and Clarence presided as Stewards of the Race. A handsome platform was by their order prepared for the accommodation of the Royal visitors, and nearly adjoining an elegant marquee was erected, in which her Majesty, the Princesses, and the Dukes of York, Clarence, and Cumberland dined.’

The Dukes of York and Clarence had also entered horses of their own into the race. Princesses Augusta, Elizabeth and Mary attended the races in 1813 accompanied by the Duke of York, and the latter also attended in 1819 and 1823, when he again acted as a steward.

The importance of Runnymede as a race track was reiterated in 1814, when Parliament passed the ‘Act for inclosing Lands in the Parish of Egham, in the County of Surrey’ on 17th June. Clause 30 of this document directed that,

‘the several Pieces or Parcels of Land, comprising the Meads called Runney Mead and Long Mead, situate in the said Parish of Egham, shall not be fenced or inclosed … but the said Meads shall … remain at all Times hereafter open and unenclosed … Provided always, that the said several Pieces or Parcels of Land last mentioned, or such Parts thereof which have been appropriated and used a long Time past as a Race Ground, shall be kept and continued as a Race Course for the Public Use, at such Time of the Year as the Races thereon have heretofore been accustomed to be kept.’

By the 19th century the venue of the annual ball had been changed from the Red Lion to the Assembly Rooms in Egham, to accommodate a greater number of revellers. The advertisement for the 1826 ball reveals that tickets cost 12 shillings and 6 pence for gentlemen, and 7 shillings and 6 pence for ladies. The price included refreshments, and the tickets could be purchased from Barnard Deane, proprietor of the King’s Head Inn. The two stewards of the ball were Charles Gordon-Lennox, 5th Duke of Richmond, and Francis Conyngham, Lord Mount Charles. The Duke of Richmond had been aide-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo, and Lord Mount Charles was King George IV’s Master of the Robes.

George IV continued attending the races, as he had done when he was the Prince of Wales. He attended all three days in 1829 when he entered ‘his favourite mare Fleur-de-lis’, and his brother William IV, formerly the Duke of Clarence, continued attending in the 1830s. The royal attendance in 1833 was recorded in detail in the Berkshire Chronicle;

‘The delightful state of the weather combined with the promised visit of their Majesties attracted a very full and fashionable attendance … The races have always been a source of considerable profit of the town … By one o’clock the assemblage on Runnymede was scarcely inferior to the best days of Egham; the sides of the course were lined – that next to the river with the stands and marquees (including Tippoo Sultan’s magnificent tents) the other with an immense number of carriages and other vehicles. The betting and other stands were quite full of respectable company. At half-past one o’clock the cheers of the spectators announced the arrival on the course of the Royal cortege; it consisted of five carriages and four; in the first were the King and Queen, the Princesss Augusta and Lord Hill: in the others were Prince George of Cumberland, Lord Albemarle, Lord Adolphus Fitzclarence, Lord and Lady Falkland, Sir Andrew Barnard, Sir William Fremantle, Sir C Thornton, Lady and Miss Taylor, Colonel Wood, Colonel Bowater, Colonel Seymour and son, Miss Wynyard, Miss Wilson, Mr Shiftner, Mr Davis, Mr Hudson, &c. Their Majesties were received with every demonstration of loyalty and respect, and took their departure amidst loud acclamations. After the first race the Royal party was joined by her Royal Highness the Duchess of Gloucester.’

King William IV presented a piece of plate worth £100 as a prize at the races in 1836, and took the opportunity to tell the spectators that he considered horse racing to be the ‘national, manly, and noble sport of a free people.’ However, his niece and successor Queen Victoria does not appear to have continued the tradition of attending the races, and indeed the account of the 1837 race paints a bleak picture;

‘These races, when on some former occasions were accustomed to be attended by all the rank and fashion of the metropolis, of Windsor, and the counties of Bucks, Berks, and Surrey, presented yesterday a most miserable appearance. The racing, that is the running of the horses, was comparatively good, and for a few moments caused sufficient excitement to induce those on the course to emerge from the booths and tents in which during nearly the whole of the day they sought shelter from the drizzling showers. What rendered the thing more tantalizing was, that at intervals the wind got up, and from the rapid transit of the clouds, some hopes were held out that the weather would clear up, and the latter part of the day make amends for the badness of the morning. The course was in some places a perfect puddle, but in that part in which the company congregated it was more firm, though not sufficiently agreeable to tempt any persons to promenade. It had been expected in London and in many places at a distance from the racecourse that Her Majesty the Queen would be present, though it was known at Windsor and Egham that it was not her intention to honour the races with her presence. This would, had the weather been in the smallest degree favourable, have operated to have brought together a great number of people. As it was, a more forlorn and scanty exhibition of equipages and company was perhaps never witnessed on the plains of famed Runnymede on a public occasion.’

However, the weather in 1838 was more favourable;

‘The company, although somewhat less numerous than had been anticipated, was highly respectable, many having travelled either by the Western Railway to Slough, or the Southampton one to Weybridge, from both which places the means of continuing the journey to the course were obtainable … An adequate police force (under Inspector Hughes, A division) was provided for the maintenance of order, and every thing done towards furthering the comfort and amusement of the spectators that judgement and liberality could dictate.’

It was reiterated in 1840 that ‘it was not the intention of Her Majesty or of Prince Albert to be present.’ The loss of royal patronage undoubtedly had a negative impact on the event’s success; it was no longer an unmissable society occasion, and gentry families gradually stopped attending. Nevertheless, the races continued until the mid-1880s, when an unfortunate dispute between the police and the race committee caused its closure.

In August 1886 a man using the moniker ‘Indignans’ wrote a letter to the Editor of the London Evening Standard concerning the abandonment of the races. He chose his name well because indignant perfectly sums up his attitude;

‘Your announcement that the annual races which have been held for so many years on the historic site of Runnymede, have been abandoned through the refusal of the Chief Constable to furnish the necessary police, will be read with widely-spread regret. It is quite true, however, that the races would have been held, and the Race Committee were prepared to carry out all the necessary proceedings, had not the Chief Constable refused to allow the usual contingent of police.

In fact, this very old and traditional meeting has been abolished by the simple fist of this functionary, and what I am desirous of inquiring is this; supposing the Committee had been unable to withdraw from the notices which had been given, and the races had been held without the attendance of the police, and had any breach of the peace occurred, whether or not the Chief Constable would have been liable for the consequences.

To my mind, it seems a monstrously high-handed proceeding, and if the Chief Constable’s power can be exercised in this way, the sooner it is curtailed the better. The loss to the little town, or rather village, through this gentleman’s act is something considerable.’

The Yorkshire Gazette reported in 1888 that the final tasks of closing the races had taken place;

‘Monday witnessed the final act in connection with these old-established races. The immediate cause of the abandonment of Egham meeting was the refusal of the police authorities to co-operate with the committee; and now, after several vain attempts, renewed each year, to obtain that assistance, the task has been given up, and the whole of the stands, railings, and other properties which have so often been erected on the historical Runnymede have been sold under the hammer.’

There seems little doubt that had the royal family still been regularly attending the races, the Chief Constable certainly wouldn’t have dared to be uncooperative. Thus ended 140 years of annual horse racing in Egham, which had begun with a small group of men racing their horses and swelled into their late 18th century heyday under the patronage of the Hanoverian monarchy.

Bibliography

- London Evening Post (London, England), August 22, 1734 – August 24, 1734; Issue 1055.

- London Evening Post (London, England), September 24, 1734 – September 26, 1734; Issue 1069.

- London Evening Post (London, England), September 26, 1734 – September 28, 1734; Issue 1070.

- London Evening Post (London, England), August 9, 1735 – August 12, 1735; Issue 1206.

- General Evening Post (London, England), September 11, 1735 – September 13, 1735; Issue 305.

- London Evening Post (London, England), August 12, 1736 – August 14, 1736; Issue 1364.

- Daily Post (London, England), Tuesday, September 21, 1736; Issue 5312.

- Country Journal or The Craftsman (London, England), Saturday, September 25, 1736; Issue 534.

- London Evening Post (London, England), June 25, 1737 – June 28, 1737; Issue 1500.

- London Evening Post (London, England), June 6, 1738 – June 8, 1738; Issue 1648.

- London Evening Post (London, England), August 1, 1738 – August 3, 1738; Issue 1672.

- London Evening Post (London, England), September 7, 1738 – September 9, 1738; Issue 1688.

- London Evening Post (London, England), May 15, 1739 – May 17, 1739; Issue 1795.

- London Evening Post (London, England), July 12, 1739 – July 14, 1739; Issue 1820.

- Daily Gazetteer (London Edition) (London, England), Monday, September 10, 1739; Issue 1317.

- Public Advertiser (London, England), Thursday, August 16, 1770; Issue 11120.

- Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (London, England), Monday, September 10, 1770; Issue 12 957.

- General Evening Post (London, England), September 16, 1773 – September 18, 1773; Issue 6230.

- Public Advertiser (London, England), Friday, September 15, 1786; Issue 16324.

- Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (London, England), Friday, September 7, 1787; Issue 18 327.

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Sep 07, 1787; pg. 2; Issue 843.

- St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post (London, England), September 10, 1778 – September 12, 1778; Issue 2730.

- Public Advertiser (London, England), Friday, September 11, 1778; Issue 13705.

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Sep 07, 1787; pg. 2; Issue 843.

- World (London, England), Wednesday, September 9, 1789; Issue 837.

- London Chronicle (London, England), September 4, 1790 – September 7, 1790; Issue 5312.

- Public Advertiser (London, England), Tuesday, September 14, 1790; Issue 17531.

- Evening Mail (London, England), September 5, 1791 – September 7, 1791; Issue 395.

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Sep 04, 1801; pg. 2; Issue 5203.

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Aug 26, 1808; pg. 3; Issue 7450.

- The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Aug 25, 1813; pg. 3; Issue 8998.

- House of Commons Parliamentary Papers; An Act for inclosing Lands in the Parish of Egham, in the County of Surrey. [17th June 1814.]

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Aug 27, 1819; pg. 2; Issue 10709.

- The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Aug 19, 1829; pg. 3; Issue 13996.

- Berkshire Chronicle – Saturday 31 August 1833

- The Times (London, England), Monday, Jun 06, 1836; pg. 4; Issue 16122.

- The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Aug 30, 1837; pg. 4; Issue 16508.

- London Evening Standard – Wednesday 29 August 1838

- The Times (London, England), Friday, Aug 28, 1840; pg. 3; Issue 17448.

- London Evening Standard – Friday 20 August 1886

- Yorkshire Gazette – Saturday 03 March 1888