Was Egham a Roman station named Bibrocum – History or Hoax?

An old index card in Egham Museum referring to an enquiry about the route of the Roman road to Silchester has faint pencil notations in the bottom left hand corner “Roman station? Bibrocum?”

…What is or was Bibrocum?

Iron Age Celts in Egham

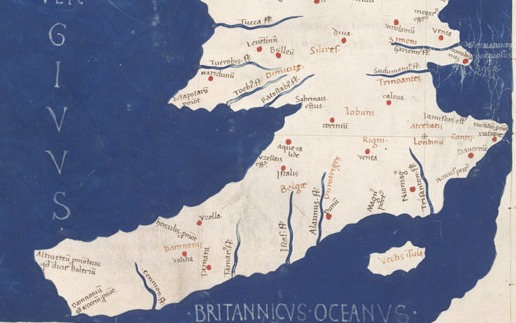

The Celts were not a single unified nation. General opinion is that the dominant Celtic tribe in Surrey before the Roman invasions was the Atrebates (see map) whose capital was at modern day Silchester (Roman name: Calleva Atrebatum).

Matters came to a head in 54BC when Cassivellaunus (leader of a tribe later known as the Catuvellauni) killed the leader of the Trinobantes, father of Mandubracius.

Mandubracius applied to Julius Caesar for support. One of Caesar’s first actions on his second expedition to Britain in 54BC was to defeat a coalition army led by Cassivellaunus near modern Brentford. Following this battle five of the British tribes involved sent emissaries to sue for peace. Caesar names these as the Cenimagni, the Segontiaci, the Ancalites, the Bibroci and the Cassi.[2]

Neither the Ancalites nor the Bibroci are named again in ancient history but it is assumed that they lived along the banks of the Thames on the north and south banks respectively. When Cassivellaunus built up his kingdom again after Caesar’s departure, the Catuvellauni occupied the north of the Thames and the Atrebates the south. The Bibroci must have been conquered or subsumed by either the Catuvellauni or the Atrebates before the major Roman invasions of 43AD.

Where could the Bibroci have lived?

Several writers place the Ancalites around Henley on Thames and the Bibroci south east of them but there is no real evidence to say where. After Caesar’s note there was no mention of the Bibroci and their home for six hundred years.

In 1586 a respected historian William Camden firmly placed the Bibroci in Bray

“The reliques of them remaine yet most evidently in the name”

and added

“Among these Bibroci, flourishes Windesor,”[3]

Since Egham continued to be regarded as a sub district of Windsor until the nineteenth century and William Camden nowhere mentions it by name we can assume that in his opinion the Bibroci lands stretched as far as Runnymede. His map (below) [4] shows them living amongst the Atrebates.

Camden also identified the place where Caesar entered the territories of Cassivellaunus as near Oatlands:

“For this was the only place in the Thames formerly fordable,”

a description which is also used of Staines, the Roman settlement of Pontes.

The Eighteenth Century Hoax

In 1747 Charles Bertram, a teacher of English based in Denmark, claimed to have found an original manuscript concerning the history of Britain written by a monk, Richard of Westminster. He sent a few ‘facsimile’ sheets to an eminent historian, William Stukeley who enthusiastically identified the writer with a fourteenth century church historian Richard of Cirencester and encouraged Bertram to publish what he had found.

The resulting book De Situ Britanniae (On the Situation of Britain) [5] first published in 1757 and in several subsequent editions, became a sensation, because of the previously unknown details it revealed about the whole country, including the Egham area and the Bibroci.

“6. The kingdom of Cantium is watered by many rivers. The principal are Madus, Sturius, Dubris, and Lemanus, which last separates the Cantii from the Bibroci.

7. Among the three principal promontories of Britain, that which derives its name from Cantium is most distinguished. There the ocean, being confined in an angle, according to the tradition of the ancients, gradually forced its way, and formed the strait which renders Britain an island.

8. The vast forest called by some the Anderidan, and by others the Caledonian, stretches from Cantium a hundred and fifty miles, through the countries of the Bibroci and the Segontiaci, to the confines of the Hedui. It is thus mentioned by the poet Lucan: ‘Unde Caledoniis fallit turbata Britannos.’

The Bibroci45were situated next to the Cantii, and, as some imagine, were subject to them. They were also called Rhemi, and are not unknown in record. They inhabited Bibrocum, 46Regentium, and Noviomagus, which was their metropolis. The Romans held Anderida.

10. On their confines, and bordering on the Thames, dwelt the Attrebates, whose primary city was Calleba.”

45 The Bibroci, Rhemi, or Regni, inhabited part of Hants, and of Berks, Sussex, Surrey, and a small portion of Kent.

46 Uncertain. Stukeley calls it Bibrox, Bibrax, or the Bibracte.

Other historians drew on this book to illustrate their own research and were keen to identify the previously unrecognised Bibrocum. For example, Edward Wedlake (1841) [7] stated that Egham

“is supposed to have been the Roman station called Bibrax or Bibrocum”

The keeper of the Cotton Library – a privately owned collection of books which had been gifted to the nation and became a founding section of the British Museum Library in 1753 – asked repeatedly to buy or see the original manuscript but Bertram refused, giving a variety of reasons and always offering to provide a copy instead. Even William Stukeley never saw the entire manuscript. Another historian Beale Poste questioned the fact that the work was listed in no manuscript catalogues of the era but answered his own query by suggesting that it could have been lost or stolen at the time of the Cotton Library’s fire in 1732.

However as the nineteenth century progressed, questions began to be asked about why no copies of Richard of Cirencester’s book existed in old libraries and why it was never referred to in pre-eighteenth century histories such as William Camden’s Britannia.

Finally B.B. Woodward, Librarian at Windsor Castle published papers in 1866 and 1867 analysing the handwriting in the original pages produced by Bertram and also the form of Latin used. He showed that the handwriting contained a mixture of styles of several different periods, including modern letter shapes, and that the Latin included literal translations of eighteenth century idiom quite different from medieval usage. An interesting one is using the word ‘statio’ for a Roman military station instead of the more usual word for a camp, ‘castrum or castra.’ He also showed that the book reproduced some mistakes which had occurred in Camden’s book, theoretically published some 200 years later.[8]

In 1869 John Mayor, a Cambridge historian who was editing a book written by the real Richard of Cirencester, completed the exposé by comparing the two publications and considering Bartram’s likely sources including its heavy reliance on William Camden.

Revelation that Charles Bertram was no better than a forger destroyed the reputations of all the historians who had relied on it for evidence, especially that of William Stukeley, and tainted others who had used it including Edward Gibbon for his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and William Roy in drawing up the initial Ordnance Survey maps. Even the genuine works by Richard of Cirencester were treated with some suspicion.

For a long time the very existence of the Bibroci tribe in England was doubted, even as a possible source for place-names such as Bray.

Despite this, copies of Charles Bertram’s forgery are easily available, especially on the internet5, without warnings about its authenticity and some history books continue to be published which cite it or later works acknowledging it as a source.

Calls have been made [9] for the whole book to be looked at again, questioning whether Bertram may have had access to unknown sources as some of his facts have been proved to be correct but this can only be done as new archaeological evidence emerges.

But where does this leave Egham?

The question of whether Egham was a Roman military camp is still a vexed one. Many Roman remains have been and are still being unearthed.[10] These certainly indicate a Roman military presence. A site investigated at Thorpe Lea Nurseries showed evidence not only of Roman occupation but also of an earlier Iron Age (Celtic period) farmstead and associated field system.

If the Romans maintained a camp in Egham they would have needed to give it a name to distinguish it from the much larger nearby town of Pontes (Staines), perhaps a name associated with the previous Celtic inhabitants, just as the Atrebates are reflected in the name Calleva Atrebatum.

Bibrocum could easily derive from a Latin term meaning ‘of or belonging to the Bibroci’ and thus be a generic name given to any place inhabited by that tribe, Bray as well as Egham.

Will we ever know for sure?

Margaret C Stewart, July 2017

[1] The 1st Map of Europe: A Latin map of the British Isles (Insulae Britannicae): Ireland (Hybernia) and Britain (Alvion), based on Ptolemy’s Geography. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Descriptio_Prime_Tabulae_Europae.jpg

[2] Julius Caesar, The Gallic Wars, Book 5 Chapter 21 http://classics.mit.edu/Caesar/gallic.5.5.html

[3] Camden, William, Britannia. https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/c/camden/william/britannia-gibson-1722/part13.html

[4] https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/f/facsimile/britannia/14030025R.jpg

[5] Richard of Cirencester, Ancient State Of Britain (1809 edition) Http://Www.Masseiana.Org/Richard.Htm

[6] This map of 1757 was based on a drawing sent by Bertram by early 1750, which William Stukeley cleaned up and reoriented to face north. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Bertram#/media/File:MappaBritanniaeFacie4.png

[7] Wedlake, Edward, A topographical history of Surrey, v.1 pt.1. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015068502569;view=1up;seq=48

[8] Bradley, Henry, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 04: Bertram, Charles

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Bertram,_Charles_(DNB00)

[9] The Kentish Antiquary, Charles Bertram’s Hoax http://history.medden.co.uk/content/charles-bertram%E2%80%99s-hoax

[10] Surrey Archaeology Unit, Extensive Urban Survey of Surrey: Egham http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-726-1/dissemination/pdf/egham/egham_eus_report.pdf