Air Raid Wardens— Badges and Whistles

Article by Joshua Whalley

This week, we will be looking at the ARP badge and whistle.

The ARP badge was awarded by Home Secretary John Simon to “persons who volunteer for ARP services and who undergo the necessary training” from April 1937 and during the Second World War. While some ARP wardens earned a wage, a vast majority gave their time freely alongside working full-time jobs. From 1936 onwards, 250,000 were produced for men and 50,000 for women. Most notably, they were given to air raid wardens who, at the peak of the war in 1942, numbered 127,000 men and women. The work of the wardens often saw them first on the scene when bombs hit during the blitz and thus their responsibilities overlapped with those of the medical and fire emergency services.

While the ARP badge was awarded most commonly to air raid wardens, there were other groups of volunteers who would receive it. Fire guards, for instance, also held observation roles in a similar vein to the air raid wardens. In certain areas, it was necessary to have all buildings monitored 24 hours a day in case they caught fire. By having a fire guard, information could be delivered more quickly to the fire service and minimise the damage done to certain buildings. When wardens or fire guards wished to report an incident, messengers were required, and these were usually drawn from the ranks of the Boy Scouts or Boys’ Brigade youth organisations. They would likely report to the central headquarters of volunteers who, upon receiving reports from wardens across the capital, would coordinate with the relevant services to respond to a situation.

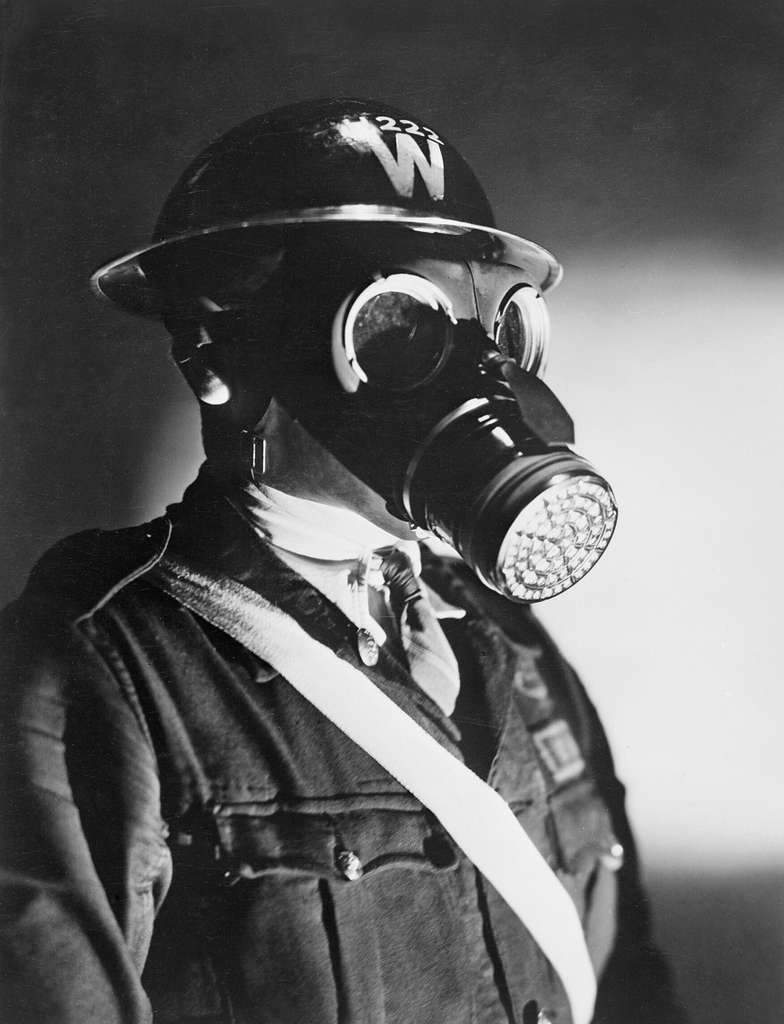

The ARP services called on most commonly by the central headquarters would have been the first aid parties, trained to give first aid response to those who suffered in bombing incidents, as well as the ambulance drivers and stretcher parties who could take the injured wherever they needed to recover. Also available were rescue services, who would recover individuals trapped inside bombed premises. These roles could largely be carried out by volunteers with minimal training, but there were also responders, such as gas decontamination, that required specialist training to safely dispose of chemical weapons. While gas masks were an effective method of protection against the threat of the likes of mustard gas, it required specially trained volunteers to neutralise the threat. This goes to show that the services required of ARP volunteers were multitudinous, and the sheer breadth of their influence in Britain’s response to the blitz was extraordinary in scope.

ARP Badges

According to the hallmarks, it was produced in London in 1936 and is made of sterling silver (925). The half-moon fastening found on the reverse also indicates that this was meant to be worn on Mr Davis’ lapel that was standard issue for men working as ARP officers, as opposed to the pin fastenings designed to be worn on the felt hats that were issued to women ARP officers. As the war progressed, and metal was prioritised towards the war effort, production of official ARP badge ceased, but miniatures made from ‘German Silver’ (copper, nickel, zinc) could be purchased from private companies for those who wished to show they were ‘doing their bit’ for the country. However, given the size, hallmarks and fastening on this badge, we can determine that this is the genuine article, awarded to a Mr Davis who was amongst the earliest to volunteer his time when the ARP programme was established.

ARP Whistle

An air raid warden is identifiable from their badge, but perhaps the item most synonymous with them is their famous whistle. Made from chrome-plated brass and inscribed with the letters ‘A.R.P’, this whistle, also donated to the museum by Mr Davis, was used in conjunction with air raid sirens to notify people that an attack was incoming. These whistles were manufactured in Birmingham by J Hudson and Co, who were also known for providing whistles commonly used by police officers. It is theorised that in order to prevent confusion when one of these whistles were blown, the ARP whistles were designed to be less sharp and shrill, and thus a passer-by would be able to identify whether a police officer was in need of assistance or if they needed to immediately take shelter. The whistle could also communicate the type of attack inbound; long blasts on the whistle indicate that an air raid is inbound imminently, where short blasts denote the dropping of incendiary devices. This is important for civilians to know, but particularly relevant to emergency services so they were informed of the type of threat they were required to respond to, and thus would be better able to deal with it. The loop implemented on one end enabled the wearer to attach the whistle to a lanyard, so they can sound a warning with minimal delay. This type of early warning communication undoubtedly saved many lives at the height of the blitz.

Sources:

ARP Whistle: https://talesfromthesupplydepot.blog/2017/12/18/arp-whistle/

Badge, Lapel, Air Raid Precautions: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30071326

Fact File : Air Raid Precautions. April 1938 – 1945: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/timeline/factfiles/nonflash/a6651425.shtml

History Of The ARP Badge – Photos, Silver Hallmarks & Valuations: https://www.ww2civildefence.co.uk/blog/history-of-the-arp-badge#comments

British /English Silver Hallmarks: https://www.acsilver.co.uk/shop/pc/British-English-Silver-Hallmarks-d84.htm

WW2 ARP Whistles For Air Raid Wardens & Civil Defence Services: https://www.ww2civildefence.co.uk/arp-whistle-lanyard.html