Educating Egham Part 2

Private Education

Although Strode’s was a free school for the poor, its early headmasters supplemented their income by taking private pupils. Some individuals earned money by setting up small schools in their homes. These were frequently short-lived and only patchy records survive. This practice continued even into the 20th Century, e.g. Mr William Butler, retired Head of the Egham Station Road schools, educated a few boys in his house in Grange Road, Egham.

A few private schools for boys lasted longer, like the academy started by John Harris Wicks in Englefield Green which existed from 1787-1825 and Egham House, a seminary for young gentlemen run by Thomas John Bailey in Egham High Street from 1839-59.

By the late 19th Century and early 20th there was a wider choice of private schools for the children from richer families who wanted something more exclusive and the opportunity to continue education beyond the age of 14. Most of these were preparatory schools, preparing their pupils for schools such as Eton or Beaumont College.

Private schools tended to offer a wider curriculum, starting with Latin and Greek and adding from the 18th Century onwards English, modern languages, mathematics and a certain amount of natural science, principally physics. By the mid 19th Century, schools in Egham – for both girls and boys – were proud to announce that they had specialist teachers for French, drawing and music.

The most successful private schools were:

- St John’s Beaumont (boys, boarding) 1888-

- Northlands (girls, boarding) 1892-1917

- Scaitcliffe (boys, boarding) 1896-1996

- Berwick House School (girls) 1914-?

- Kingswood (Catholic girls, boarding) 1921-1955

- St David’s (girls, boarding) 1922-1966

- Runnemede House (girls) 1932-1966

- Virginia Water Prep (girls) 1933-1996

- Manor Lodge (boys) 1930 -1945

In 1818 Wicks’s Academy advertised:

“The peculiar character of the studies is classical but great attention will be given to every useful pursuit that the elegant scholar who shall have made great attainments in polite studies may not be found wanting in that kind of learning which is indispensably necessary to the ordinary purpose of life.”

Curriculum

The earliest education was intended for boys who intended to become monks or priests and focused on the teaching of Latin. Lay education saw the priority as reading and writing and a basic understanding of the Bible. In 1704 Mary Barker left money to be used to teach children of Englefield Green to read the Bible in English and girls to sew, make plain work and to knit. The Mistress of Christchurch School in 1893, Annie Harriet Brant, was qualified in “freehand, Geometry and perspective”. She introduced Drawing as an examination subject for boys but not girls.

In the early 19th Century The National Society held that “the National Religion should be made the foundation of National Education, and should be the first and chief thing taught to the poor”, plus reading, writing and arithmetic. These subjects remained the basis of the elementary school curriculum for most of the 19th Century , although a survey of 1838 found nearly half of all pupils were only taught spelling, with very few being taught mathematics and grammar. Parents did not expect more than this.

In 1905 an Englefield Green parent requested that “Girls should learn the elementary rules of health and hygiene, of cooking, ironing and the making of their own garments… [boys] the nobility of honest labours, of true manhood, to develop a strong physique and the privilege and duty of citizenship.”

After 1944, grammar schools offered a wider range of subjects. The National Curriculum was introduced in 1988 to ensure that all schools were offering the same standard of education in: English, Mathematics, Science, Art & Design, Citizenship, Computing, Design & Technology, Languages, Geography, History, Music and Physical Education.

Teachers

With no formal teacher training before the second half of the 19th Century, the characters and abilities of teachers varied enormously. Three of the most interesting teachers in our local history were John Harris Wicks, Sophie Weisse and Thomas Jeans.

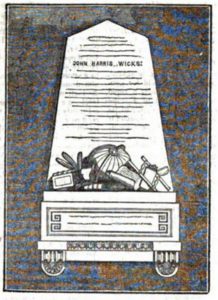

John Harris Wicks ran an Academy in Englefield Lodge, Middle Hill 1797-1817. He was described by his most famous pupil Thomas Love Peacock as “not much of a scholar; but he had the art of inspiring his pupils with a love of learning.” He published at least 2 books on teaching accounts and book-keeping. After his death, a monument was erected in Egham Church to mark his 30 years’ contribution to local education and plans were made to distribute bread and clothing to the poor on his birthday.

Sophie Weisse, the daughter of German musicians who had settled in Edinburgh, established Northlands, which was to become a fashionable school for young ladies, in London Road in 1892. Her protégé and most distinguished pupil was Scottish pianist and composer, Sir Donald Francis Tovey for whom she commissioned a new house in 1911 – The Pantiles (now Forest Court) in Simon’s Walk. In 1936 he presented her for the honorary degree of Doctor of Music at the University of Edinburgh in recognition of her services to music. Together they organised Chamber Music Concerts at Northlands from 1893-1914, featuring many famous musicians. The school had closed by 1919 but Sophie Weisse continued to live in Englefield Green until her death in 1945.

At the age of 57 Thomas Jeans was an unlikely choice for the position of headmaster at Strode’s School in 1807. Originally from Hampshire he was educated at Winchester and Oxford and in the 1770s he served in France as chaplain to the British Ambassador. When he married in 1786 he became Rector of two parishes in Norfolk. These do not seem to have been fashionable enough for his taste and he left them in the care of a curate from 1796 until his death in 1835.

He brought his wife and children to live in Knowle Green, Staines and acted as a curate at St Mary’s Church Staines until 1810 and as a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex and Surrey. When the position of Headmaster became vacant in 1807 he was one of only two applicants – the other was rejected for not being a clergyman.

Dr Jeans proceeded to turn the Strode’s schoolhouse into his own private dwelling where he could teach fee-paying sons of the well-to-do.

A government survey of 1818 reported that “the curate [Dr Jeans] thinks that the education in the endowed school is too good for the poorer classes, who are the objects of the will.”

He installed an assistant in a building next to the Crown public house to teach the poor children specified in Henry Strode’s will. A lawsuit brought by shocked Egham residents in 1812 forced the school to revert to its original charitable status and Jeans to be suspended for some months. After reinstatement Jeans sold his own land to the Coopers’ Company so that a new larger school could be built to his design. He and his assistant remained in post until his death but Dr Jeans only visited the school for some 10-15 minutes a day.

Portrait of Mrs Jeans and her two sons Thomas and John , by John Russell , Louvre.

© RMN-Grand Palais – Photo M. Urtado