Educating Egham Part 4

Educating Girls

The earliest schools were intended only for boys – even when benefactors such as Henry Strode left money for the education of children. Mary Barker’s legacy specified that girls were to be taught to sew and knit as well as read the Bible. The aim was to prepare girls for lives as wives and mothers.

Unusually the charity school established by Sir William Perkins, in Chertsey accepted girls alongside boys from 1736. From 1819 under-subscribed places at the school were opened to boys and girls from Egham, Thorpe and Staines. The earliest girls’ school in Egham seems to have been Berryman’s Ladies Boarding school (1794) of which no details survive.

However as fee-paying schools for girls appeared, such as the Gloucester House Establishment run in Egham by Mrs Hollis 1821-1825 under the patronage of the Duchess of Gloucester, they tended to stress deportment and appearance over academic subjects. A few years later fashionable schools for young ladies added French, drama and drawing, e.g. Miss Mary Sherley’s Ladies’ Seminary in Egham High Street between the years 1851-1867 included on its staff a music teacher and a language teacher from Paris. Even in the early 20th Century private schools for girls, like Miss Portway’s School for Young Ladies 1900-1934 in Egham and Northlands 1892-1917 in Englefield Green, still placed a strong emphasis on music and languages.

Later schools became more academic in flavour (Berwick House School 1913-1938, Egham; Runnemede House 1932-1966, Egham; Kingswood, Catholic, boarding, 1921-1955, Englefield Green; St David’s 1922-1966, Englefield Green; Virginia Water Prep 1933-1996) and copied boys’ preparatory schools in preparing girls for the Common Entrance Exam for public schools, especially Wycombe Abbey

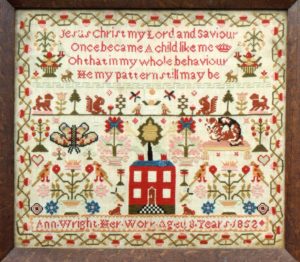

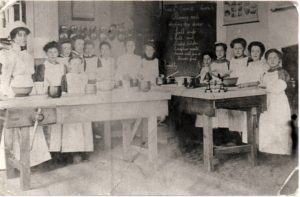

Away from the private sector, National and Board schools accepted both girls and boys from the start but they did not always follow the same curriculum. Girls would be denied some of the more academic subjects to spend time on needlework and baking. At least they were taught to read and write, and the level of female literacy rose from 40% in 1840, to 60% by 1860.

However, a report by the Schools Inquiry Commission in 1868 criticised the ordinary course of instruction for girls as being very narrow and unscientific, and reformers worked to improve education for women.

In Englefield Green in 1905 controversy greeted Local Education Authority plans in 1905 to save money by educating girls and boys together. A visiting speaker, Professor Minchin informed an Egham Parish Council meeting in December 1905 that after a certain age, girls’ minds were not sharp enough to keep pace with boys and that mixed classes would lead to “indelicacy on the part of the girls.” Parents expressed fear that mixed classes would injure the moral tone of children and lead to “undesirable freedoms.” They were promised that classes would be carefully supervised and that playgrounds would still be segregated – a practice which continued into living memory.

When Strode’s became a grammar school in 1919, the Strode’s Foundation offered scholarships for girls to attend Sir William Perkins’s School – but this depended on parental co-operation and many girls were not give the chance to apply for schooling after the age of 14.

Successive Education Acts from 1880 to 1944, which made school attendance compulsory and abolished fees in state and church schools, opened education to girls from all classes.