Egham and the Empire: Cards and Collectibles

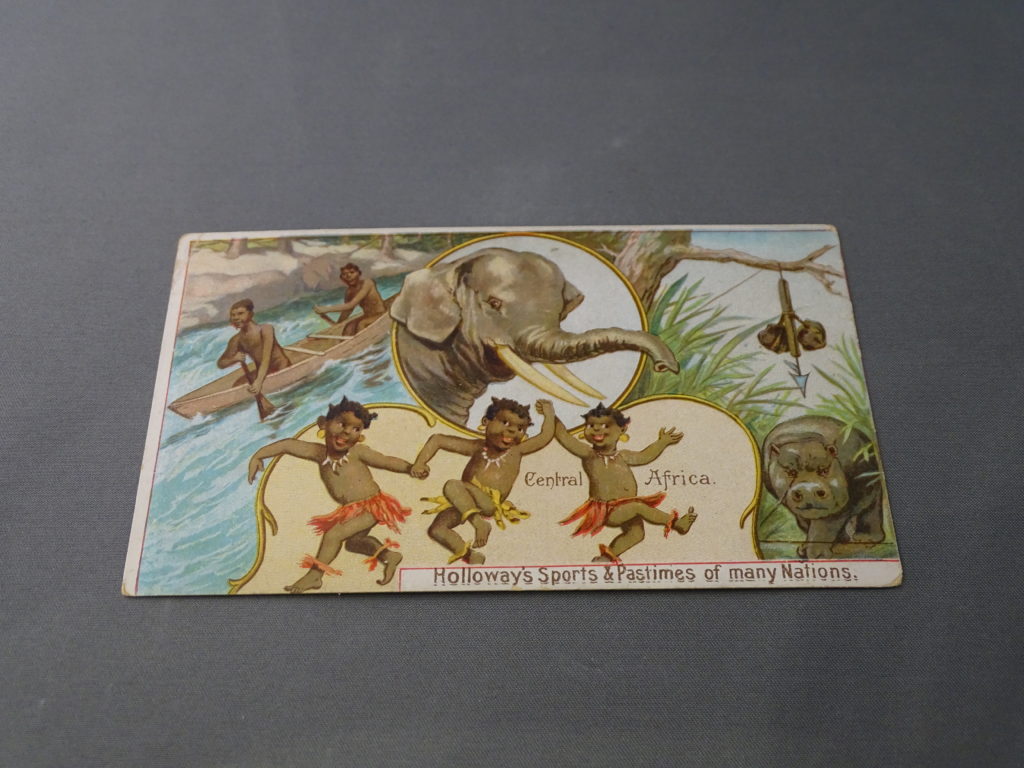

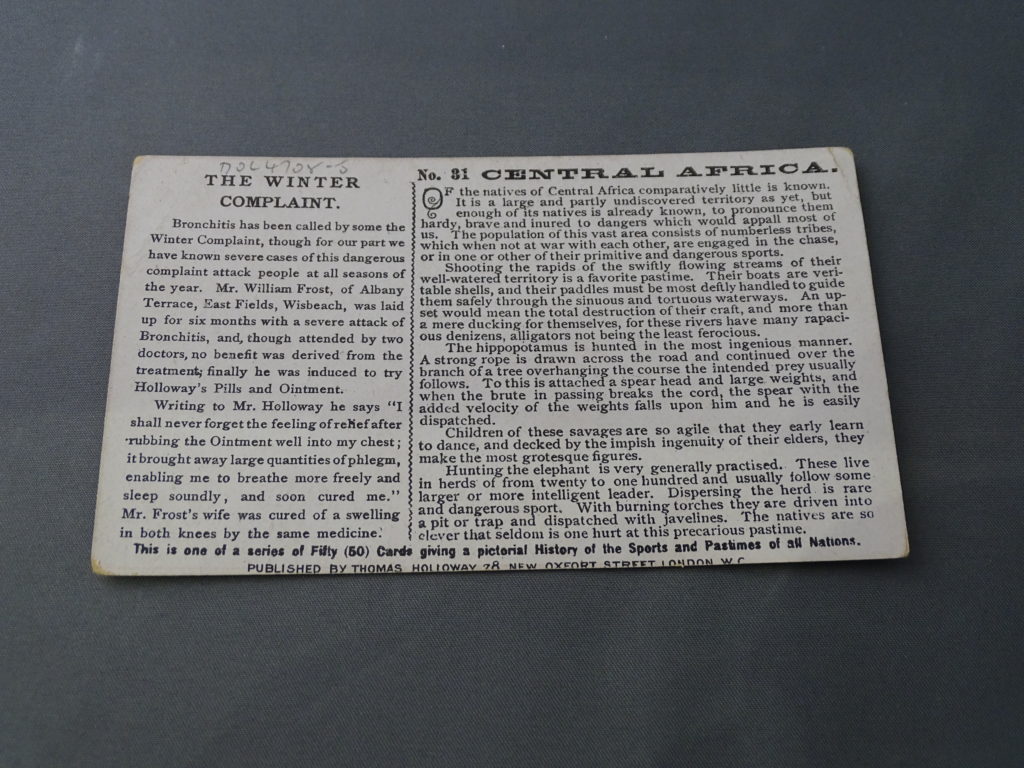

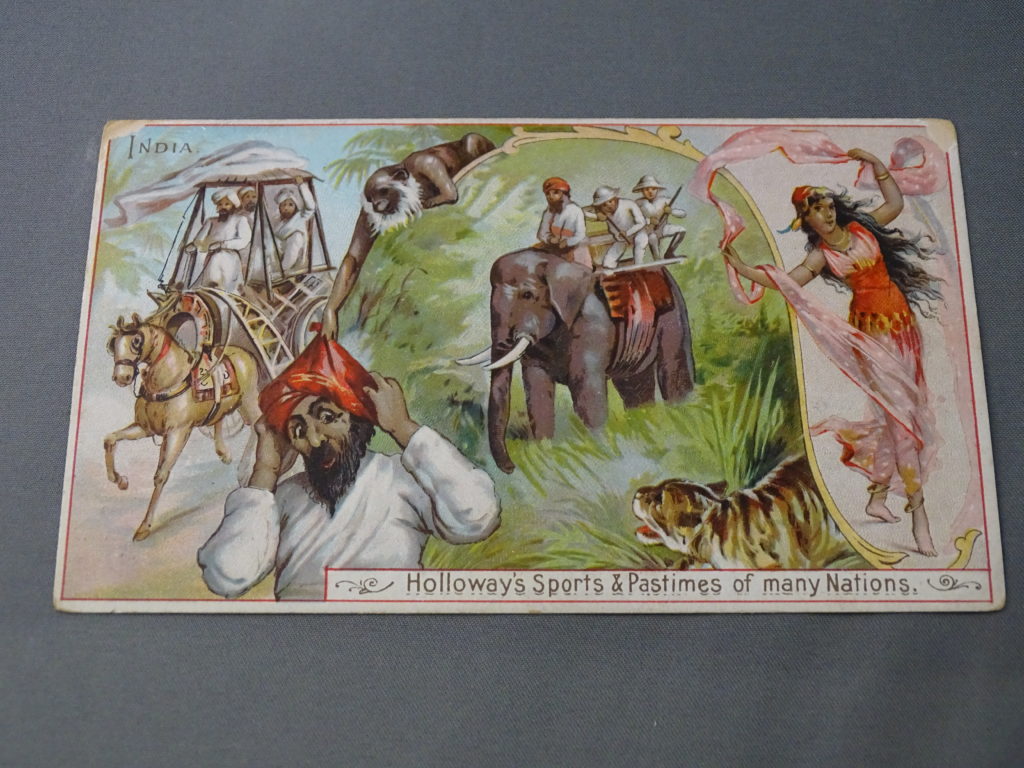

Significant to Egham, these trade cards [1] were produced by Thomas Holloway, the founder of the nearby Royal Holloway College and The Holloway Sanitorium [2]. The construction of these buildings changed the history of our local community forever, and his legacy still impacts Egham today. Trade cards such as these were used throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century to advertise businesses. Much like the business cards of today, they were handed out for free to prospective customers. Cheap and easy to produce, these cards ensured that a potential consumer would know what the product was and the business that it came from. Business owners sought to make their trade cards as eye-catching and colourful as possible, so much so that many people began to collect them as a hobby.

These trade cards form part of a larger set of fifty, titled ‘Holloway’s Sports and Pastimes of Many Nations’. Thomas Holloway published these trade cards at a time when there was growing fascination with Britain’s overseas territories and colonies. These would have caught the attention of those who had never seen the landscapes or peoples that the cards supposedly depicted. Holloway knew that these cards would be popular with the public, which would help to generate more interest in his own ointments, benefitting his business.

Although the set includes countries that have no significant imperial connection to Britain, a number of cards are used to represent Britain’s imperial territories. The ways in which the indigenous populations are depicted highlight the stereotypes that existed. These stereotypes were entrenched in British imperial culture. The depictions and language used also explicitly reflects the racist attitudes that were prevalent at the time. By depicting these peoples as stupid or lazy ‘savages’, Britain’s aggressive colonial operations were represented as a moral and religious duty. Many racial stereotypes had their roots in European imperial science, which can be traced back to the 1700s with the study of supposed ‘differences’ between each ‘race’.

Note the difference in imagery and language for the card which represents the ‘Anglo Saxons’[4]. During this period many British people believed that British society was one of the most progressive in the world, and in part popular culture encouraged the belief that it was Britain’s destiny to bring ‘progress’ to ‘uncivilised’ peoples. During the nineteenth century many British people believed that the European ‘race’ was racially superior in comparison to the other ‘races’, partly as a result of their Anglo-Saxon heritage.

Although Holloway’s own fortune was not directly linked to colonial wealth and goods, these cards suggest that he was aware of the popular views linked to British imperialism and sought to gain a profit from these popular beliefs through the production and distribution of these cards.

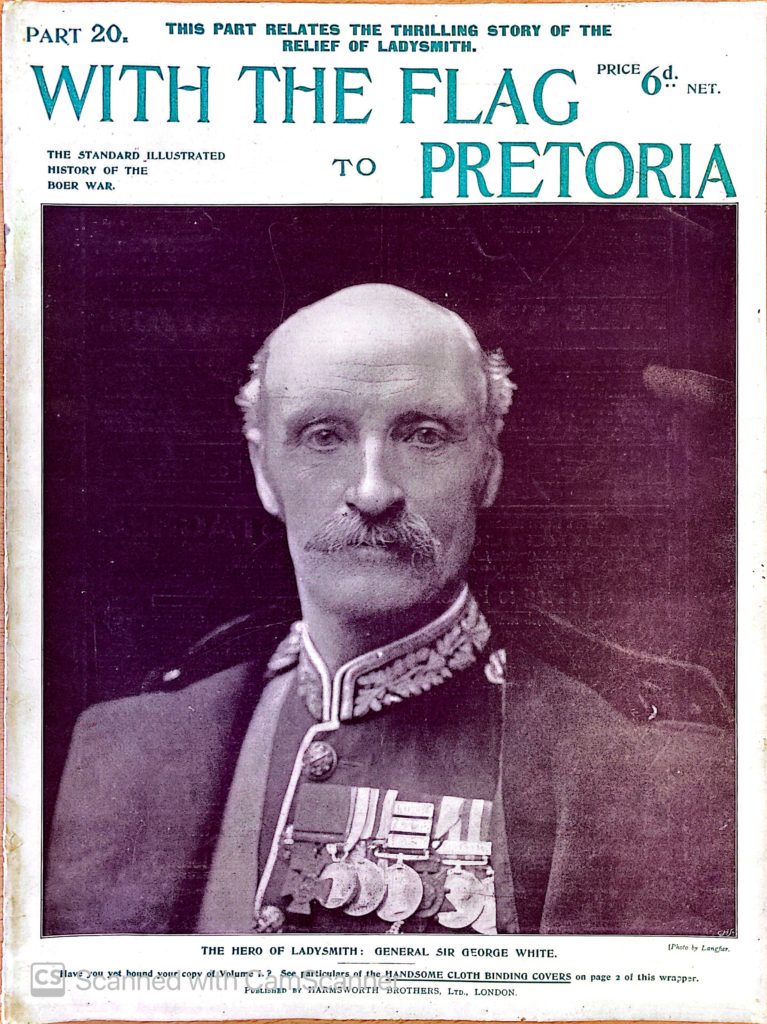

This newspaper supplement [5] illustrates the popularity of empire-related ephemera at the turn of the century. This particular issue covers the military contribution of Sir George White, who was considered a hero of the Boer War and at one time lived at Trevethan House, Englefield Green. The supplement details the exploits of the British, celebrating their victory against the Boers. These pamphlets emphasized the courage of the British troops and their supposed military superiority through the use of clever tactics. This is typical of imperial popular culture of the period, which often featured real or imaginary skirmishes with local populations of empire.