Organisations of Empire: Colleges, Celebrations, Schools and Societies

Training Colleges

After the 1857 Indian Mutiny, India officially became a territory of the crown. Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India in 1877, and in 1878 The East India Company, who had effectively ruled India from the mid-1700s onwards, was officially disbanded through an act of Parliament.

Various colleges were set up across Britain in order to train the next generation of bureaucrats who would ‘rule’ India on behalf of both the government and crown. Training institutions were needed in order to train these individuals for their eventual role in India through offering engineering and forestry courses. Although not linked necessarily to imperialism in material and popular culture, institutions like these became commonplace across Britain and known within society. The declaration of Victoria as Empress of India in 1877 brought the ruling of India into the public consciousness, where it was nicknamed ‘The Jewel in the Crown’ of the British Empire. This was partly due to its valuable raw materials and luxury exports.

This postcard from our collections show the Royal Indian Engineering Training College [1], which was situated on Coopers Hill, Englefield Green, from 1871 until 1906. The use of this photograph on a postcard demonstrates how the empire could feature in all kinds of ordinary and everyday interactions, such as the sending of a postcard to a loved one. This photograph also suggests that it is a notable building, following the conventions of traditional postcards, which often feature popular or historically significant locations.

At the college, men were trained as engineers, telegraphists or as forestry experts. After completing their studies students would then go on to participate and oversee the completion of various public works in India. Colonial careers offered men from the upper middle classes the opportunity to accumulate greater wealth and real colonial power. The work required ambitious young men to oversee the continuing British control of India, and so required individuals who were unafraid of the possibility of tropical disease or harsh conditions.

Many Coopers Hill students were drawn from the leading public schools of Britain, which often emphasised values such as loyalty and honour. Militaristic undertones were commonplace throughout the curriculum, mainly through basic military training and parades. The values emphasised in both public schools and colleges such as these aligned perfectly with imperialistic beliefs, such as fulfilling your duty to your country. The college was also known for its physical education and sports competitions, where students could participate in a wide range of sports, such as golf or cricket. The trophy from our collections further highlights the college’s emphasis on sportsmanship and achievement. These were celebrated and formed an important part of the college’s curriculum.

The college remained open until 1906. One of the reasons for its closure may have been because by the early 1900s, the colonial office increasingly sought for British colonial policy to remain a mysterious topic to the wider British public. This prevented any widespread knowledge and therefore criticism at colonial policy, especially as a result of such a patriotic and imperialist fervour that was present. After the First World War many colonial officials were drawn from a select few families, making it difficult for ‘outsiders’ to gain a role in colonial governance and policy making.

Empire Day

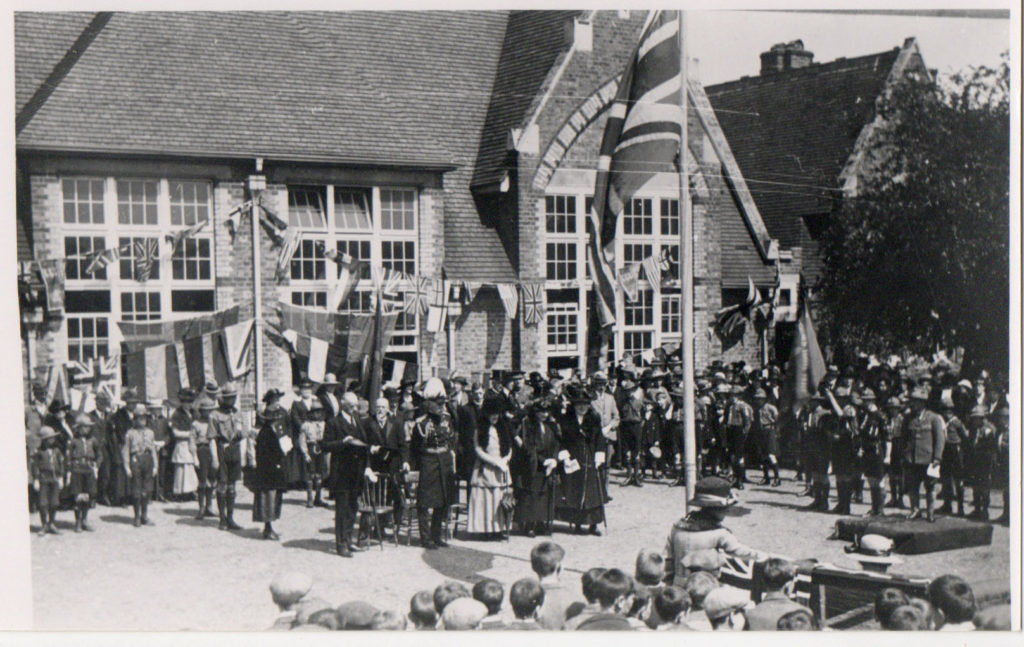

Aside from royal events such as historic jubilees or coronations, many ordinary people celebrated Britain’s imperial achievement through the celebration and ceremony of Empire Day [2]. In our photographs, pupils from Egham [3] and St Jude’s school [4] are seen celebrating Empire Day in the early twentieth century. Photographs depicting similar celebrations were commonplace throughout areas of both Britain and in colonial territories such as Australia and Canada.

Empire Day had its origins in 1890s Canada, where it was introduced by schoolteacher Clementina Fessenden. It was designed to foster feelings of patriotism and imperial togetherness in schoolchildren across the Canadian provinces. In our photograph of St Jude’s School [4] a large banner reads ‘One King, One Flag, One Fleet’. This slogan was designed to promote the idea of a collective colonial community, which later in the century would evolve into the idea of a commonwealth collective.

The 12th Earl of Meath, Reginald Brabazon, was inspired by the work of Fessenden and attempted to replicate the day back in Britain. He was enthusiastic about Britain’s Empire and had previously worked in the Foreign Office, whose employees were responsible for the handling of various colonial affairs.

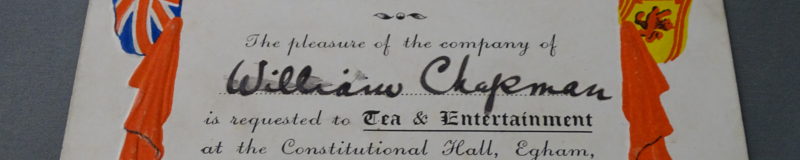

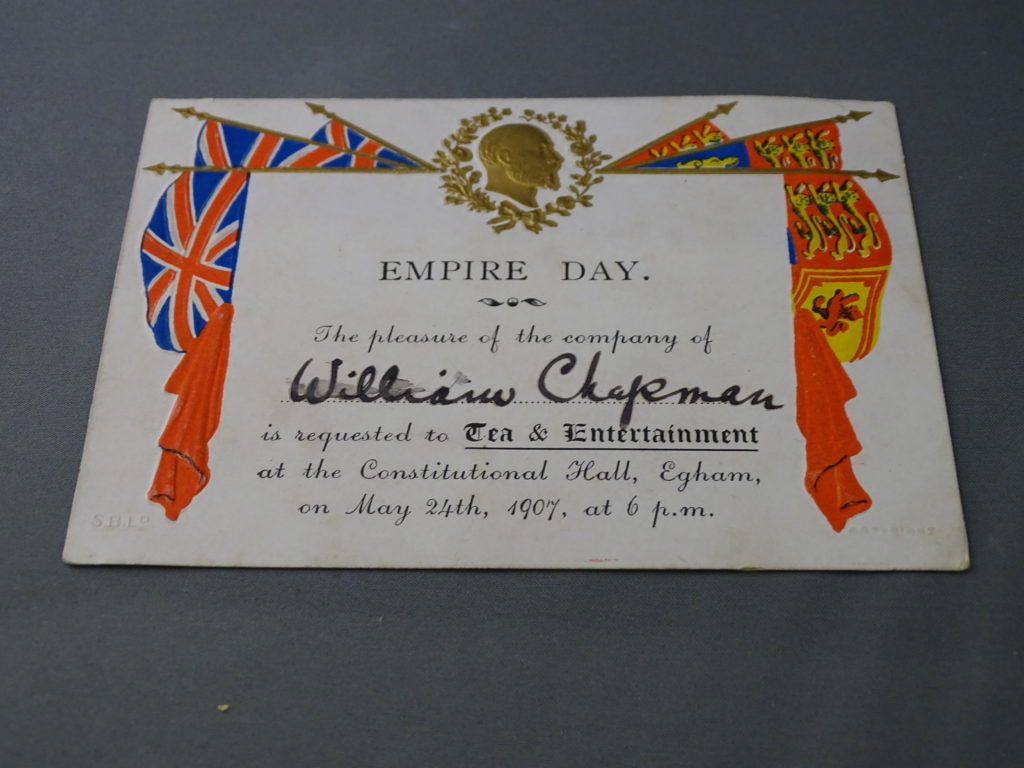

Brabazon was successful in his goal of bringing Empire Day to Britain, and the first ever (unofficial) Empire Day in Britain took place on the 24th of May 1902, the same date as the late Queen Victoria’s birthday. Our 1907 invitation for a William Chapman to attend Empire Day Celebrations in Egham [5] suggests that it was a lavish affair, with promises of ‘tea and entertainment’.

It was not declared an official day of celebration on Britain’s calendar until 1916, but had been enthusiastically celebrated, particularly in schools since its introduction. The day itself steadily grew in popularity with the wider British public and was commemorated in the press. Events such as parades, military processions and concerts took place to celebrate the day. There was a wealth of popular culture based on empire that was circulating in Britain at the time, and fascination with Britain’s overseas territories was seen across British society.

For children, Empire Day meant decorating classrooms and playgrounds with the Union Jack flag. The singing of patriotic songs and lessons linking to imperial territories were also common, and in some cases colonial officers would visit and give speeches. Patriotic plays were also sometimes performed, which may explain why in our image of Egham School a boy is seen dressed up in a recreation of a tropical colonial uniform.

Similar traditions and celebrations took place in schools and in other settings across Britain’s various territories. Empire day would have undoubtedly been a day of great excitement and fun for children. Historians have suggested that the imperial message was often lost on children, who often saw the event only as a chance to escape the boredom of schoolwork!

After the Second World War, the popularity of Empire Day declined and drew criticism from many groups within society, eventually resulting in Empire Day being formally removed from the national calendar in 1958. However, the day was then re-named Commonwealth Day and continued to be celebrated on the same date until 1973. It was then moved to the second Monday in March, the date on which it is still celebrated today. The most prominent event during the modern Commonwealth Day is an annual church service that is attended by the monarch and senior members of the royal family every year.

The Freemasons and Empire

A recent addition to the collections of Egham Museum, this Freemasons medal [6] was donated by a local individual with family connections to the Freemasons. The Freemason’s were officially formed in the early 18th century with the founding of ‘lodges’ in Britain. As the British Empire began to grow, so did the influence of the Freemasons, who set up numerous ‘lodges’ across the empire. This may explain the inscriptions ‘For God’ and ‘Empire’ seen on the medal. It is unclear what the medal was awarded for, partly due to the secretive nature of the organisation. The medal was awarded in 1972, demonstrating how the idea of empire was still very much present within society after its decline, in this instance through utilising the imperial ideas of the past.