Egham’s Flying Fortress

Egham, like many small towns in the south east of England experienced its fair share of tragedy during the war. On the 16 November 1940, Luftwaffe bombs fell on Arkell’s drapery shop in the High Street killing two boys evacuated from Stepney, East London and the young daughter of the family. Later, during a raid on the night of the 9 January 1941, the area between Milton Park and Egham Hythe was set alight when 200-300 magnesium incendiary bombs were dropped. Moments later a heavy bomb fell on Mullens Road, Pooley Green destroying 22 houses, leaving a 15ft deep crater and killing eight people.[i] However, a far more bizarre chapter to Egham’s wartime story was soon to be added when an American bomber crashed onto Long Meads on the outskirts of Egham.

The Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress, that was to become Egham’s Flying Fortress, was attached to 323rd Bombardment squadron of the First Bomb Division of the 91st Bombardment Group of the United States Eighth Air Force.[ii] On New Year’s Eve 1943 it set out on a daylight raid over Southern France, primarily targeting Luftwaffe airfields in Bordeaux with secondary targets in Cognac.

Wider Bombing Objectives

The crews actions over France was part of wider operations undertaken by the 91st Bombardment Group in attacking and crippling German airpower. This was part of Operation Pointblank which targeted Luftwaffe production and assets, such as planes and airfields, in an effort to soften Western Europe for an eventual Allied invasion.[iii] It also had the added effect of drawing Luftwaffe assets away from the Eastern Front and the Mediterranean.

American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress Bomber

The American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was a very different bomber from that in the arsenal of Great Britain and Nazi Germany. Unlike those operated by Germany, it was a four-engine, heavy, long-range behemoth. The Luftwaffe never operated four-engine long-range bombers, favouring medium twin-engined bombers such as the Heinkel HE 111 or Junkers Ju 88, lacking both the payloads and range of their four-engine Allied equivalents.

Perhaps the most interesting distinction comes when comparing the Flying Fortress to its RAF equivalent the Avro Lancaster. Both were four-engine, long-range, heavy bombers. The difference came in the payload and armaments. As noted by Richard Holmes, the B-17 carried so many gunners that its payload was half that of RAF bombers.[iv] The difference in armament arose from the American belief in daylight raids over that of night bombing which was favoured by the RAF. The Americans favoured accuracy over the protection of night. As such their bombers had to defend themselves from both enemy fighters and flak from AA guns thus justifying a lesser payload for greater defences and better precision. British bombers by contrast, benefitting from the cover that night provided, implemented fewer gunners and emphasised greater payloads allowing them to inflict greater damage and account for diminished accuracy by bombing a greater area.

The 8th USAAF also heavily subscribed to the concept of self-defending bombing formations, which also likely played a role in the design of the B-17G and its numerous gun emplacements. Failing to learn lessons from the Battle of Britain and the heavy losses suffered by Luftwaffe bombers when deprived of fighter escorts, they failed to acknowledge the need for fighter escorts when raiding during the day.[v] Simply put, bombers, regardless of the their defences lacked the manoeuvrability to effectively challenge fighters. The Americans learned this lesson harshly in 1943 with their theory of self-defending bombing formations savagely disproven and Egham’s Flying Fortress was likely a victim of this ill-advised doctrine.

Poor Conditions and a Confused Crew

Upon their return from France, the crew were greeted with dense cloud cover and approaching darkness. Becoming increasingly lost and unknowingly leaving their formation, Egham’s Flying Fortress looked for a suitable place for an emergency landing. Its crew had lost use of its navigation and communication instruments and became increasingly confused, not knowing where they were and unsure of their fuel levels. Meanwhile, residents in Staines reported seeing an aircraft circling overhead. One resident, Mr D. Clark stated later that he saw the aircraft with one engine on fire and another inactive. Later, at 17:30, it was seen following the River Thames past The Causeway gas works.

Mr Ronald Thomas, then a boy living at 86 High Street Egham, reported seeing the aircraft flying towards Runnymede and “miss[ing] Stopps’ Chimneys by inches.” Meanwhile, concerned witnesses at the foot of Egham Hill garage had spotted the aircraft and telephoned the Police Station who then contacted the Fire Brigade. The last and perhaps most dramatic account of the aircraft’s final movements was recorded by Mr Doyle. He was a driver for Thomas Roberts, ballast supplier of Wraysbury, returning home at the end of the day in his ABC lorry, from Old Windsor to Egham via Long Mead. He recalls the terrifying moment when he saw the aircraft hurtling at his lorry, claiming that it came as close as 5 feet from him. The aircraft was likely travelling at 90 mph when it touched down, so Doyle certainly had the closest encounter and was lucky to be unharmed. The bomber’s final resting place was adjacent to the Windsor Road, opposite Magna Carta Island.

Crash Scene and Inspiration for our Model

Initially the crash site was difficult to locate by first responders who were uncertain whether the aircraft was German or Allied. One of the fire fighters, still at that moment unable to find the crash site, shouted in what was by that point the darkness of night and made contact with the crew and located the crash site. The crew of the B-17 was initially under the impression that they had landed in France, so were overjoyed when they learned they were in Britain. The crew claimed they were short of fuel and that their radio was out of action due to damage sustained from enemy fire. One of the firemen took the pilot to the nearby Bells of Ouseley where he telephoned Northolt to report the crash and that the crew were all unharmed. Later the remaining nine crew also arrived at the Bells of Ouseley were they dined and spent the remainder of New Year’s Eve.

The report of the crash scene by Engineering Officer Major Ben T. Stogner noted that the majority of the damage was sustained from the crash landing but that there was minor flak damage to No.4 oil cooler fairing and one small flak hole in the main cabin door. Interestingly there was still 300 gallons of fuel on board, furthering the evidence that the crew became hopelessly confused. Later, a safety mishap report which official described the incident as a crash landing, dispelled Mr Clark’s account of seeing fire coming from one of the engines, noting there was no significant damage to the engines.

Many Egham residents who had heard the commotion of the plane flying overhead and fire engines screeching as they searched for the crash site, ventured out to investigate: they explored the wreckage and quietly helped themselves to ‘souvenirs’. In fact, many eyewitnesses reported their surprise to see live ammunition still on the ground the next morning. In the days following the crash, the War Reserve Police, encouraged by American authorities who had by this time taken over guarding the crash site, ordered Egham locals to return what ‘souvenirs’ they had taken. Whether everything was returned remains a mystery.

Egham’s Flying Fortress was, over the following few days, cleared and taken away and most likely used for scrap as the plane was too badly damaged to be repaired and return to operations. The crew who had survived the crash had mixed fortune throughout the remainder of the war. All had been reassigned to another bomber and just days later were shot down. Five of the crew were killed when they crashed while the other five became POWs.

Continuing Legacy

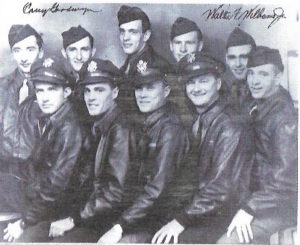

Egham’s Flying Fortress was largely forgotten post-war until renewed interest was ignited in 1983 when it was reported that the Society was researching the events of the crash in the Staines & Egham News. Along with this, society members shared some of their experiences, such as Jean Bell, whose husband was a War Reserve Policeman and tasked with getting Egham locals to return their ‘souvenirs’ from the crash site. Vivian Bairstow also published a booklet detailing the events of Egham’s Flying Fortress in 1985, with a 3rd edition published in 2018. In 1992, a descendant of one of the crew, Mr Willard Wolf visited Egham Museum and presented a copy of the crew photograph as a donation.

A model of the crash site was created by Phillip Hancock and presented to the museum as a donation in 1993. Expertly made with painstaking care and attention to detail, it perfectly recreates the crashed B-17, complete with Egham locals excitedly inspecting the scene. The model shows not only accuracy with the scene of Egham residents inspecting the crash site, but also the damage done to the aircraft when it landed. Complete with landing gears severed from the torso of the aircraft, flattened gun pod at the belly of the aircraft and blackened, upturned earth from the rough landing. It also contains the squadron insignia, American star of the USAAF and yellow serial numbers on the tail fin.

The model of Egham’s Flying Fortress is currently on display at Egham Museum as our contribution to Surrey Museums Month.

CALLUM PEARS, MAY 2018

For a more detailed account of the event that inspired the model of Egham’s Flying Fortress, consider buying Vivian Bairstow’s booklet Egham’s Flying Fortress: A Wartime Crash on Runnymede, available for £1.50 at Egham Museum.

For Further Reading of Egham’s Flying Fortress see:

Bairstow, Vivian. Egham’s Flying Fortress: A Wartime Crash on Runnymede. Egham: Egham-by-Runnymede Historical Society, 2018 (3rd edition).

Williams, Richard. Runnymede: A Pictorial History. Addlestone: Egham-by-Runnymede Historical Society, 1995.

For Further Reading on the history of the B-17 throughout the Second World War see:

Holmes, Richard. The World at War: The Landmark Oral History from The Classic TV Series. Reading: Ebury Press, 2011.

Carey, Brian Todd. ‘Operation Pointblank: Evolution of Allied Air Doctrine During World War II,’http://www.historynet.com/operation-pointblank-evolution-of-allied-air-doctrine-during-world-war-ii.htm#sthash.LVTkglZ5.dpuf Historynet

Eighth Air Force Historical Society. ‘Missions Details; Airfield in France December 31, 1943,’ http://www.8thafhs.com/old/get_one_mission.php?mission_id=580 Eighth Air Force Historical Society

Flightglobal Archive. ‘Flying Fortress (B-17G): A Survey of the Hard-hitting American Heavy-weight: Eighth of the Fortress Line and Fifth to See War Action,’ https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1944/1944%20-%200915.html Flightglobal Archive

Perri, Nancy. ‘Dallies of the 323rd Squadron 1943,’ http://www.91stbombgroup.com/Dailies/323rd1-1to3-30-43.html 91st Bomb Group

Zhou, Jing. ‘B-17 Bomber Fortress – The Queen of the Skies: The Crew,’ https://b17flyingfortress.de/en/details/die-besatzung/ b17flyingfortress.de

Further Reading of Egham’s experiences during the War see:

Davis, Dorothy. The Egham Picture Book. Addlestone: Egham-by-Runnymede Historical Society, 1988.

———————————————————————————————————————

[i] Dorothy Davis, The Egham Picture Book. (Addlestone: Egham-by-Runnymede Historical Society, 1988), 52-3.

[ii] There is some disagreement regarding which squadron Egham’s Flying Fortress belonged to, Vivian Bairstow’s book claims it to be the 324th squadron, but the Eighth Air Force Historical Society (EAFHS) points to it being in the 323rd Squadron. The EAFHS states that only the 322nd, 323rd and 401st battle squadrons of the 91st Bombardment Group flew on New Year’s Eve 1943.The reference to heavy cloud cover in the 323rd’s mission report further points to Egham’s Flying Fortress belonging to the 323rd. Eighth Air Force Historical Society, ‘ Missions Details; Airfields in France December 31, 1943,’ http://www.8thafhs.com/old/get_one_mission.php?mission_id=580 Eighth Air Force Historical Soceity

[iii] For more information on operation Pointblank see; Brian Todd Carey, ‘Operation Pointblank: Evolution of Allied Air Doctrine During World War II,’ http://www.historynet.com/operation-pointblank-evolution-of-allied-air-doctrine-during-world-war-ii.htm#sthash.LVTkglZ5.dpuf Historynet

[iv] Richard Holmes, The World at War: The Landmark Oral History from The Classic TV Series. (Reading: Ebury Press, 2011), 423.