Egham’s Police Force

First patrols

Despite its distance from London, Egham and Englefield Green were included in the Bow Street Horse Patrol. The patrol was originally founded in 1763 to have a presence patrolling the highways in and around London, but it died out due to a lack of funding after 18 months. It was revived in 1805 by Sir John Fielding, who despite being blind could recognise 3,000 criminals by voice alone. The new and improved Bow Street Horse Patrol had 60 men patrolling from the centre of London outwards towards places like Windsor.[1] Bow Street Patrol men were recognisable from their uniform, as they were the first uniformed police force in Great Britain. They wore blue jackets with brass buttons, a leather hat, blue trousers and leather boots; but what made them stand out were their scarlet waistcoats, earning them the nickname of ‘robin red breast’.[2] As officers they carried a cutlass, truncheon and pistol as a form of protection. The patrol was very effective in removing highwaymen from the roads into and out of London, particularly Hounslow Heath, until they were disbanded by the government, and the highway men returned.

Appointment of Special Constables in Egham

In an 1822 letter to Charles John Lawson Esq, Clerk of the Peace, the establishment of special constables in Egham was outlined. Various local residents named in the letter were worried about the number of felonies happening in the local area, both in the past and present. Because the men named were of ‘fine respectable households’ in the Parish, their call warranted the introduction of special constables in the local area, made up of local volunteers, to police during the upcoming winter. This was allowed under an Act of Parliament in 1820 during the reign of George IV, which gave magistrates the power to appoint Special Constables in time of public unrest, but local authorities were often reluctant to appoint them.[3]

The Surrey Constabulary

The idea of establishing of a police force outside of the Metropolitan police district was first brought up in December 1850. It was decided that the 96 parishes would be put into 3 divisions: Dorking, Godalming and Chertsey, with Dorking housing the chief constable. The Surrey Constabulary then became operational in the New Year in 1851, with 70 police officers, including 5 superintendents, and the chief constable, Captain Hastings. Officers had to be less than 30 years old and at least 5 feet 7 inches, but there was no minimum age, and a 14 and 15 year old were recorded as officers.[4]

In 1898, there was talk of introducing telephone communication between the Surrey police stations; the Surrey Standing Joint Committee wrote to the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police about the matter. They argued it was of particular importance for Egham and Staines to have a phone line because they communicated about all petty felonies within the area, and it would save them from having to cycle between the stations. The Met didn’t greet the suggestion with much enthusiasm, and thought it benefited Surrey more than it did them. The connection then never went ahead.[5]

Egham Police during World War Two

During the Second World War, many police officers went to the front, because many were reservists and already trained, and many young officers volunteered. This meant the police force across the UK was spread thin, so the government introduced some measures to stop officers going to fight. In addition, they recruited reserve policeman, more women, and more special constables.[6] The special constables were still active in Egham from the previous century, and seemed to have increased during wartime; there were 130,000 special constables across the country in the Second World War, a number which hasn’t been reached since.[7] Throughout the war years, it was difficult to leave the position of special constable, as seen in a letter to all special constables in 1945, which said the restriction on the right to resign was now lifted. The letter did still encourage the constables to maintain their position, as they were always an important part of the police force.

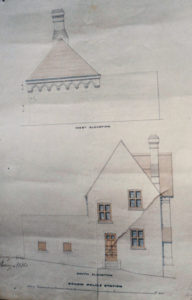

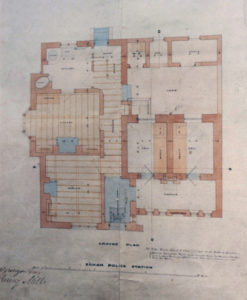

Egham Police Station

Before the first Egham Police Station was built in 1859, other local buildings were used as a police station. In 1843, before the inauguration of the Surrey Constabulary, the Egham Vestry converted 62 The Avenue from a former poor house into the first iteration of the police station. Simultaneously they appointed Parish Constables for Egham. In 1858, part of the Literary Institute, which currently houses Egham Museum, was used as a police station before one was purpose built by the Surrey Constabulary. Egham Police Station was built in 1859, 8 years after the establishment of the Surrey Constabulary, at the bottom of Egham Hill. It remained there until 1937, when the police station moved to the site of Denham House on the corner of Egham High Street and Vicarage Road. This closed in 2013, and the police station moved to the Runnymede Civic Centre.

The local police force is now based at the Runnymede Civic Centre in Addlestone. Photo Credit: runnymede.gov.uk

[1] Vic, Bow Street Horse Patrol: fighting crime during the regency era, Jane Austen’s World, 23rd January 2007, available from <janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2007/1/23/bow-street-horse-patrol-fighting-crime-during-the-regency-era>

[2] Alan Cook, Public Offices, Truncheons and Tipstaves, available from <truncheon.org.uk/Middlesex>

[3] The History of the Special Constabulary, Old Police Cells Museum, <https://www.oldpolicecellsmuseum.org.uk/content/history/police_history/police_specials>

[4] Robert Bartlett, Part 1: Policing the Victorian Countryside, International Centre for the History of Crime, Policing and Justice, <https://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/history-from-police-archives/RB1/Pt1/pt1SryConstab.html>

[5] Bartlett, Part 1: Policing the Victorian Countryside, International Centre for the History of Crime, Policing and Justice, <https://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/history-from-police-archives/RB1/Pt1/pt1TL189201.html>

[6] Bartlett, Police during the Second World War, International Centre for the History of Crime, Policing and Justice, < http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/history-from-police-archives/PolCit/polww2.html>

[7] Karen Bullock and Andrew Mille, The Special Constabulary: Historical context, international comparisons and contemporary themes, (Taylor & Francis, 2017) p5