Health, Holloway and Hype Part 2

Read part 1 here

Holloway Sanatorium: Treatments, Staff and the NHS

Treatments: A Healthy State of Mind

Prior to the advent of the NHS in 1948, Holloway Sanatorium was intended as a place to cure those people who were middle class and mentally ill. It was not a place for longer-term care. Holloway Sanatorium’s approach was “to incessantly apply in all cases constant psychological and physical treatment with a view to stimulating a return to a healthy state of mind” (Annual Report 1934).

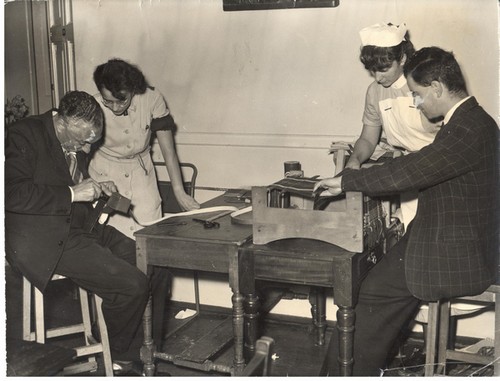

From its early days, Holloway Sanatorium provided occupational therapy, attaching importance to the occupation and recreation of patients as a means of cure. The Sanatorium encouraged participation in exercises, arts and crafts, musical performances, and regular walks in its beautiful surroundings. Patients could even visit the local village and Virginia Water Lake. In 1905, over 50% of patients were “usefully employed” and 60% attended the weekly entertainments. Nursing staff and attendants were employed for their arts and music skills and, by 1940, the Sanatorium’s Occupation Therapist had three assistants in order to support patients.

For many years the Sanatorium had a seaside villa, originally in Brighton but later in Bournemouth, whereby some patients would be sent to benefit from the different surroundings.

However, there were many other, less pleasant, treatments given to patients. These included restraints, such as straps and jackets, used to stop patients injuring themselves or others and, despite national concerns about the potential for abuse by staff, such practice continued into the 20th Century. Straightjackets were used when patients were first admitted to the Sanatorium but this practice was less common by the 1950s – unless a patient was brought in by the police.

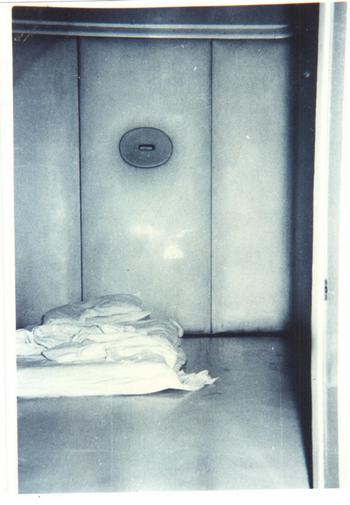

Seclusion was also a form of restraint with patients confined in places such as ‘strong rooms’ which contained only a bed, chair and small table. There were four protected or ‘padded’ cells at Holloway, two on the male ward and two on the female ward. In these rooms, the walls were literally padded, and the floor was made from a grey, rubbery, waterproof material. A drain ran around the edge of the room. There would be a mattress on the floor, strong canvas sheets, and a rubber pot was provided for sanitation. Patients could not be secluded without permission by the ward doctor, with seclusion lasting from 8am until 8pm, before the order had to be renewed. These rooms were removed from the Sanatorium in the 1970s.

Medication and surgical procedures were used, where appropriate, as the 20th Century progressed. In the 1930s, the drug, Cardiazol, was introduced as a form of shock therapy for schizophrenic patients where high doses would induce convulsions. The 1940s saw electric shock therapy used solely or, in conjunction, with a modified insulin shock method for those in depressed states or schizophrenia. Leucotomy (known as lobotomy in the United States) was an operation which severed a frontal portion of the brain, and the Sanatorium reported good results in several cases. By 1947, the Sanatorium reported that insulin, prolonged sleep treatment, electroplexy, leucotomy and “every modern physical method of treatment” (Annual Report 1947) was used daily.

Staff and Families: The Employee Experience

Holloway Sanatorium employed a large number of people from its inception. The first Medical Superintendent overseeing the Sanatorium was Dr Rees Phillips (1884–1899). By 1892, there were 51 Day Nurses, 12 Night Nurses and 29 Lady Companions overseen by a Matron and Head Male Nurse; additionally, the cohort of domestic staff was similar to that found in a large stately home.

Prior to the Nurses Registration Act 1919, many of the Sanatorium staff achieved the Certificate of Proficiency in Mental Nursing, administered by the (Royal) Medico-Psychological Association (RMPA). During the early 20th Century, Holloway Sanatorium Annual Reports listed those nurses and attendants who had passed the Medico-Psychological Examination at the Sanatorium, as well as detailing the length of service of some staff – in 1905, the Medical Superintendent noted that “of the 56 [staff] who have gained the ‘St. Ann’s’ medal, after five years’ service, 44 are still with us” (Annual Report 1905, p.12). By December 1947, the Sanatorium’s Preliminary Training School for female student nurses was opened. Trainees were required to attend for 8 weeks before entering the Sanatorium wards. Nurses were taught the theory and practice of nursing delivered by a qualified Sister Tutor, along with lectures and demonstrations given by Doctors and other senior members of the hospital. It was not just examinations that helped ensure a high standard of care by staff for patients but, up until the establishment of the NHS, all hospitals and sanatoriums for the mentally ill had to be inspected twice a year by a Commissioner in Lunacy or, from 1913, the subsequent Board of Control for Lunacy and Mental Deficiency which ensured standards were maintained for patients.

In 1919, the Nurses Registration Act established the General Nursing Council (GNC) for England and Wales and was given statutory responsibility for the training and registration of nurses, including mental health. The new body was soon in conflict with the RMPA and the two organisations ran rival training schemes for mental health nursing for over 30 years.[1] The GNC’s Registered Mental Nurse (RMN) and the RMPA’s nursing certificate (RMPA cert.) continued to co-exist until 1951, when the RMPA scheme ceased.

The GNC’s three year Registered Mental Nurse course or the four year Psychiatric and General Nursing Course would prepare candidates, including those trainees at the Sanatorium who had completed their 8 week preliminary training course, for the State examinations in order to meet nursing requirements. By the 1950s, once suitably qualified, nurses in their first year could earn £230 per year, working 48 hours a week with one month paid annual leave. A pension was also provided. It was noted in 1954, that there had been prejudice against mental nursing but this attitude was beginning to disappear due to “the increasing recognition of the importance of psychiatry.”[2] Whilst in a Sanatorium brochure, c.1950s, the Matron encouraged all potential nursing recruits to: give this branch of nursing a trial, for by helping to rehabilitate these patients to take a useful place in society you would be sharing with them the happiness that comes with the return of mental health.[3]

There was an active social calendar for the Sanatorium’s staff and their families each year, with dances, plays, fairs and days out; as well as onsite facilities, by the 1950s, such as an open-air pool, a weekly cinema show and out-door sports and games, some involving both patients and staff. There was also a Chapel onsite which was used for weekly services and the building was positioned to allow staff easy access and exit to the patient wards, if necessary. Sanatorium patients would also engage with staff and their families, as well as members of the local community who would join activities in the grounds of the Sanatorium, such as hosting school sports days. This left a lasting memory on the children of employees, as Meryl Camp recalls: “[the Sanatorium was a] safe and happy normal neighbourhood. Within the walls was a world and home for patients, staff and families… My most favourite occasions were the cinema and the Christmas party for the children, which was held in the dining hall with Santa each year with presents.”

Health Care for All

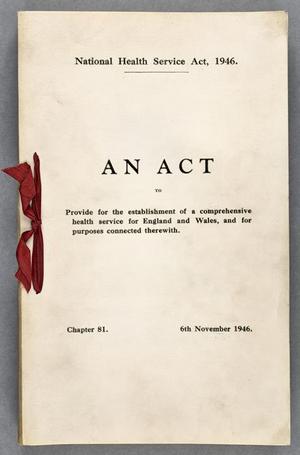

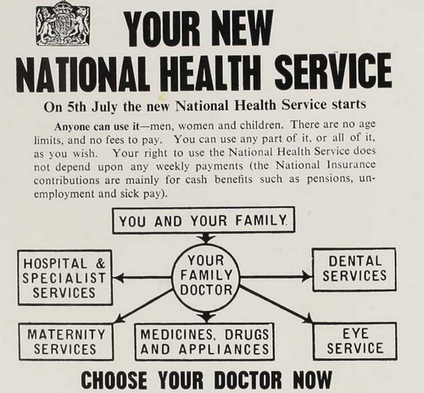

On 5th July 1948 free healthcare, based on need rather than the ability to pay, was introduced in Britain. The National Health Service (NHS) was launched by the then Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan, who promised that “everybody, irrespective of means, age, sex or occupation shall have equal opportunity to benefit from the best and most up-to-date medical and allied services available.” The Act brought together a wide range of medical services under one organisation, including hospitals, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, opticians and dentists. Initially, many doubted it would last more than a couple of years but demand for healthcare exceeded all predictions.

The introduction of the NHS led to Holloway Sanatorium no longer being a fee paying institution but becoming an institution under the NHS. Several of Holloway Sanatorium’s Board of Governors, Trustees and Committee Members resigned, stating in the 1948 Annual Report that they “did not feel able to carry on under the new conditions.” The Report goes on to outline the ‘Advantages and Difficulties of Our Position Under the National Scheme’. The Management Committee carefully considered Thomas Holloway’s founding wishes to offer ‘a curative establishment’, alongside the anticipated increase of ‘incurables’ who would now be non-fee paying patients under the new scheme. This, combined with ongoing financial challenges, meant that if they were to remain outside the new scheme, the Sanatorium would have to increase their fees and restrict “the section of the community for whom our Founder intended this Sanatorium”.

Overall, the Sanatorium’s Management Committee felt that, with the state’s help, they could continue to fulfil the original intentions of Thomas Holloway on a far larger scale than previously.

Read Part 3 here

Our ‘Health, Holloway and Hype’ exhibition was proudly funded by the Royal Holloway, University of London, Citizens Project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

References

1. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00674.x

2. A Handbook for Mental Nurses (1954) RMPA, 8th ed. (London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox), p.283.

3. Holloway Sanatorium for Nervous Disorders brochure (c.1950s), p.8.

General References

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Birth-of-the-NHS/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-44560590

https://www.hsj.co.uk/home/mental-health-history-taking-over-the-asylum/1136349.article