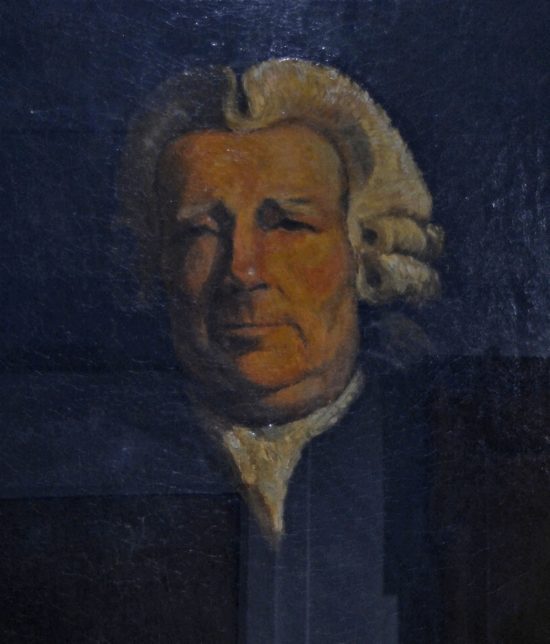

Henry Strode and his Legacy

Henry Strode (1645-1704)

Reproduced with kind permission of the Principal.

Henry Strode (1645-1704), was born into an old Egham family but lived most of his life in London with his father. Strode’s father was a member of the Worshipful Company of Coopers, and at the age of 16 Strode became his apprentice. Seven years later he was admitted to the Company and shortly after became a partner in the family business. After his father’s death and following in his footsteps, Strode took over the family business and became Church Warden of St. Laurence Pountney Parish Church (in the Candlewick Ward of the City of London). Although the Church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666, the original graveyard still remains and the Strode gravestones can still be found there.

On his retirement, Henry Strode returned to Egham with his widowed sister as his housekeeper and her young son Henry Herring. He was living in Egham when he was made Master Cooper in 1703, only a few short months before his death. His diary entries from this period of his life reveal much about his deeply religious roots and his ties to the community, and go some way to explain why he left the sum of £6,000 in his Will to found a free school and almshouses in Egham on his death.

‘Now consider a natural man in his best circumstances I suppose him to be born of religious parents, that his parents took great care in giving him good example and good admonition to instil and inculcate continually into his mind excellent holy and true notions of God and goodness for that he has the advantage of an excellent education which yet but few have’.

The Worshipful Company of Coopers

The Worshipful Company of Coopers is one of the livery companies of the City of London; the earliest known reference is from 1298 when it was a guild of like minded individuals working as coopers in the City. These ‘fraternities’ were commonplace and an important feature of social structures in early times, for many (especially poorer craftsmen), it was a way of assuring protection of the ecclesiastical au

thorities, as well as aid and guidance through life. They were also charged with ensuring appropriate standards were maintained in the production and use of wooden casks, which in those days and beyond were the standard container for a great variety of goods. These included not just beer, wine and spirits, but also water and food on voyages. Nelson’s body was returned to England in a cask of French brandy, proving that casks have many uses. Whereas the Company used to control cask making rigidly in London, it lost that position principally during the eighteenth century with the rise of the Royal Navy and its need to produce and repair casks aboard ships.

Today, the Coopers has evolved into the trustee of six charities, and a social and charitable enterprise that focuses on the craft of cask making.

Egham Poor Boys School

Henry Strode believed in the benefits of education and in his Will, entrusted the sum of £6,000 to the charity of the Coopers with which to build his school for poor boys in Egham. The school opened its doors over 300 years ago in 1706, along with almshouses. Within the original site, the school rooms were located in the central building, with the male accommodation in the left block, and the women’s accommodation to the right – the idea behind this was to ensure the men were further away from any temptations of the Crown Inn.

The early years of Strode’s School were somewhat caught up in conflict between the Company of Coopers and the people of Egham – for who should make the key decisions over the employment of School Master and who should nominate the almsfolks when vacancies appeared? After a long legal case, the Court of Chancery eventually decided that the estate was vested in the Company, which gave them power of nomination.

These legal conflicts were not to be the last of the school’s troubles. In 1807 the Reverend Thomas Jeans was appointed Master of the school, an appointment that aroused much suspicion from the locals. Not only was he a clergyman but also a magistrate acting as justice of the peace in both Surrey and Middlesex; his incomes were far larger than his position warranted and it was known to the community that at least three of his sons were at Winchester College. Just five years later, it emerged that he was in fact abusing his position as Master and taking in boarders of gentlemen’s rank for a fee to bulk his own personal income. He also altered the school building to allow him his own private apartments, removing a small classroom to provide a family dining room. To add insult, it was also found that the poor boys were in fact lodging in a room at the nearby Crown Inn rather than in the school, and being taught by a ‘sickly and infirm person from Chertsey’.

On the discovery of these deceits, the Company set about to rebuild a more suitable schoolhouse separate from the Masters’ quarters, and on request of the parishioners, were not permitted to accept any fee-paying scholars. Reverend Jeans remained in his post until his death in 1835, suffering only a short suspension for his misdemeanours in 1813. At this time, the school taught 40 boys. The School remained as a charity for poor children until 1900 when it was eventually closed to be rebuilt as a secondary school for boys in 1919.

A Secondary School for Boys

The Education Act of 1870 meant that elementary education was soon being provided by the State. The Egham School Board, established in 1884 until 1902, opened the Egham Hythe Schools in 1886 and St. Ann’s Heath School in 1896. As a result, it was felt that Strode’s could be best utilised as a secondary school.

The School closed in 1900 and reopened in September of 1919 as a Grammar School, with 62 boys and a teaching staff of just 2 full-time teachers, 3 part-time teachers and the Headmaster, Mr J. Mylam Gittins.

Inter-war Education

In 1924 a sixth form opened, consisting of 15 boys. Most sixth formers at Strode’s in the 1920’s had the modest ambition of another term or perhaps another year working on school certificate subjects in order to raise their achievement to a credit, or to make up the required clutch of subjects to be eligible to enter Higher Education.

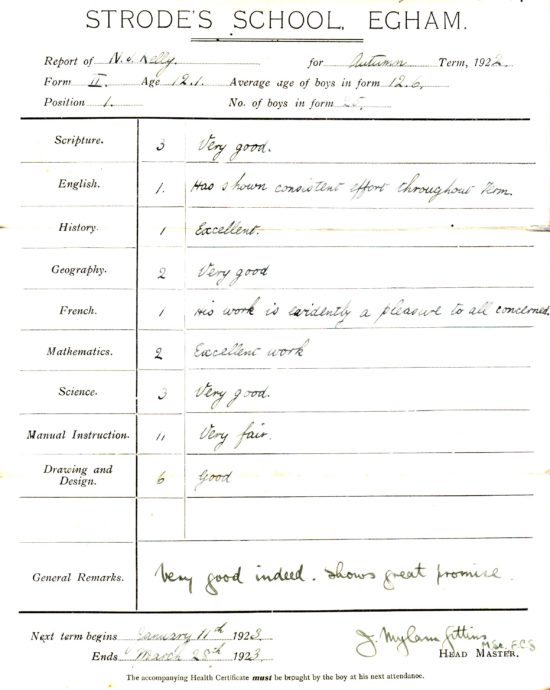

A wonderful example of a Strode’s pupil’s educational progress in the 1920’s is that of Norman James Kelly who was awarded a scholarship in 1922, went on to pass his general school exams and became a Reverend.

Strodians at War

War time did not deter the pupils at Strode’s: lessons continued and should there be an air raid, an alarm would sound and everyone would move to the inner corridor of the building away from the danger of the windows should they shatter, or traipse to safety in the basement. It was noted in the 1944 edition of The Strodian school magazine that, “Due to flying bombs only [swimming] competitors were allowed to proceed to the baths, so the events took place amid less noise than usual.”

Most of the senior boys joined the local A.R.P and a few enrolled in the Home Guard. In the school itself the Fire Guard comprised of staff members and senior boys.

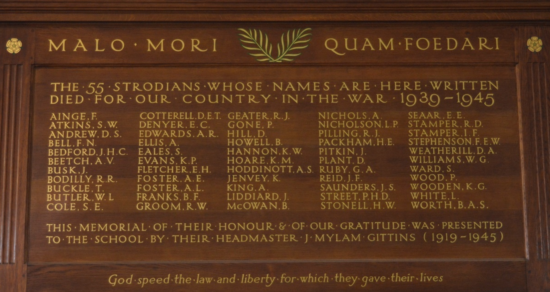

World War II: ROLL OF HONOUR

Like the rest of the country, Egham and Strode’s suffered at the hands of the War. Sadly fifty-two Strodians died for their country during 1939-1945; their names, plus 3 further Strodians, are listed on a Roll of Honour that hangs proudly in Strode’s College in Coopers Hall. The memorial was presented to the school in 1954 by the former Headmaster, Mr J. Mylam Gittin.

School Rules

Like all schools, Strode’s had certain rules that had to be followed. The first rule listed in the 1920’s rule book read:

(1). General Discipline. Silence must be maintained in the corridors of the school at all times between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. There is be no shouting, running or playing in Cloakroom, Corridors or Classrooms.

Former Strode’s pupil John Webb, recalls that “Head Master Gittins had much trouble getting us to obey this general discipline rule. He was often prowling about the corridors between classes when much room-changing took place. On one occasion someone pinned a paper notice on the back of his black gown, which read “clown”. If the perpetrator was caught he probably got “six of the best”, a punishment given rarely by Mr. Gittins.”

The following rule was stuck to page 8 of the Rule Book and therefore must have been added because of the incidents referred to:

(19). Forbidden Imports. The following must not be brought into the school grounds or premises without special permission from the Head Master:-

(a) Any mechanical device for projecting any solid, liquid or gas, including toy and blank pistols, fireworks and other explosive or inflammable materials.

(b) Any instrument that can be used for cutting, piercing or hitting.

(c) Any golf ball or solid ball of any size.

(d) Any livestock, whether considered harmless or not.

Taken from Strode’s School Rules, 8pp. a small book (2″ x 4″) with the school coat of arms on the green cover, Robinson Brothers, Egham, 1920s. Price 2d. a copy (0.8250 of a 2016 penny).

Old Strodians Association & The Masonic Lodge

In March 1925, a group of former pupils decided to set up the Old Strodians’ Association. The annual subscription was five shillings (25p) and a life membership was three guineas (£3.15p).

Competitive sport against other school teams and organisations was at the heart of the Association. Soon, an Annual Dinner was introduced in 1930. During these early years, there was a busy programme of activities including a motor run to Woking, a supper at the Catherine Wheel pub, a fancy dress dance, a Walk by Night and regular support was provided to the Boat Club.

The Old Strodians’ Masonic Lodge, Lodge Number 7803, was established in 1962, with W. Bro. Lewis Kent as its first Master.

Strodian Memories: John Webb

In 1940, the Battle of Britain was in full swing. The autumn term began. Fleets of German bombers on their way to and from London, passed over our house in daylight. One morning I heard the pulsing roar of aircraft engines: Mr. Green came into our classroom (on the High Street side of the school) and climbed the ladder set in place, up to a skylight. He immediately rang the alarm. I knew, as did many others in the class, that the aircraft was a Junkers 88. We all went into the corridors; the emergency passed.

By the age of fifteen I was fire-watching at Strode’s for one night a week. The fire-watching group each night was three pupils and one teacher. The students slept in the lunch room and the teacher slept in the headmaster’s office. Supplies were provided so that we could cook ourselves a hot meal in the evening and morning.

At Strode’s, many changes had taken place by the end of the 1940-1941 year. We now had three women teachers for English, History and Physical Education. The last also was an excellent pianist and accompanied the Swedish exercise competitions directed by Mr. Green, who has served in the Great War. The other two I got to know well, because I continued with English and History (as well as Geography), to the Higher School Certificate. I sat the exams for this just before I joined the RAF in 1944. The History teacher was Miss Sams, a good teacher, who lived in the Railway Hotel in Virginia Water. The third teacher was Marjorie Slade, who always took an interest in what I did. I even took a minor part in a play she directed put on in Egham in 1943. Marjorie Slade was a first rate teacher. It is still sad to me to record that she died soon after the war in a train accident on the Waterloo to Egham line.

The Geography Teacher was Lionel Stamp, a bluff and private man whose whole life, it seemed, was dedicated to the pupils at Strode’s. In 1942, 1943 and 1944, he organised and directed summer camps for about 40 boys, where we worked on the tree holdings of the forestry Commission in Surrey, Sussex, and Monmouthshire. “Sticky” also took us on field trips and was the football coach for many years. He lived on well into his nineties, always in the same rooms in a house just off the Strode’s playing fields.

I took eight exams in the General Certificate examinations, taken at age 15-16. In my last two years at Strode’s I studied only three subjects, or disciplines, as I was beginning to see them. I had hundreds of hours of teaching in very small classes, many, many essays to write and books to read. Many of the books we were assigned to read in school were intolerably tedious – there were exceptions, for example, Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and Old Mortality; some of The Natural History of Selborne by Gilbert White, and the plays of William Shakespeare, most of which I had read by the age of eighteen.

On almost all schooldays I travelled to school by train from Virginia Water to Egham. On trains going the other way were lots of girls on their way to Sir William Perkins School in Chertsey. We were in an all-boys school, they were in an all-girls school. We boys told each other questionable stories and whispered to one another about the girls we saw in Egham High Street or Station Road. The girls stood in little knots on the other side of the road and were no doubt whispering to each Other as they looked at us. This was in the late afternoon as we came out of Strode’s in droves.

Post-War Boys’ Grammar School

On Founders Day 13th July 1954, the school welcomed H.R.H the Duchess of Kent to mark the 250th Anniversary of Henry Strode’s death. The Duchess of Kent laid the foundation stone of the new library. Further developments took place with the opening of the new laboratories in 1961.

The four school houses were called, Charter, Coopers, Paice and Strode’s and healthy competition was had by all. Sports had always played a core role at the school throughout its history, and there were various active teams in football, table tennis, hockey, cricket, tennis and boating. Other clubs and societies included drama, cross country, photographic, chess and aeronautical.

Strodian Memories: Vivian Bairstow

Having passed my 11+ whilst at Choir School, I moved to Strode’s Grammar School in 1960, staying until 1965. Strode’s had about 440 pupils during my time there and of course, it was a day school for boys aged from 11 to 18. This meant that boys were at the school when they needed to take GCE O and A levels.

The uniform was a dark green blazer with a gold and dark green striped tie, black shoes, grey trousers and white shirt. Boys arriving at 11 wore short trousers, moving to long trousers generally at 13. If a boy became a prefect (those that weren’t called them defects), he wore a black blazer instead of dark green. Also, there was a different tie worn if a boy was in the boat club, although it was only the design that changed rather than the colours.

I lived in Egham town at the time, so generally went home for lunch, but there was the ability to eat school dinners which were served at the Church Hall in Church Road, moving later to a dining room at the school. The dining room was where boys were given milk in one-third of a pint bottles, at break time in the mornings.

Boys generally came from a catchment area of Addlestone and Chertsey to the south-east, Virginia Water to the south-west, Egham Hythe to the east and Englefield Green to the west. The boundary reflected the fact that there were different education authorities in the local state sector, such that Strode’s would not naturally take boys from Middlesex, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, whilst other Surrey schools would take boys from say, Weybridge.

Discipline included occasional corporal punishment, and the usual essays and lines, but of course, there was an innate discipline in having to wear uniform and behaving oneself off site. On the other hand, there was an increasing move to relaxation in society at the time, such as the advent of the swinging sixties, so that it must have challenged the teaching staff how to retain standards.

The teaching staff had generally been at Strode’s for many years and there was a high proportion of them that had served in the armed forces in the Second World War.

Each morning started at 9 o’clock, followed almost immediately by a short daily assembly, involving the whole school up to the fifth year. Besides the requisite Christian element to assemblies, there were talks rather than sermons given by masters and visitors, e.g. a local vicar or other person of interest.

All of the above reflects school life, but of course, it is what pupils made of it which is also important. I feel that all pupils would have agreed that attending Strode’s gave one an advantage in life, as represented by good public exam results and subsequent further education and careers.

Strode’s Foundation Today

In 1975 Strode’s began its move into a Sixth Form only college by ceasing to admit 11 year olds, along with the addition of a mixed gender Sixth Form. It proved to be a testing time for Strode’s with tensions between the existing Grammar boys and Sixth Form students.

A City & Guilds course was introduced in 1983 for students who wanted to continue to study, but who did not have higher education as a goal. This marked the first step towards open access to all who wanted to study post-16. The former temporary gymnasium, built in 1966, was transformed to the long-awaited library and sports hall in 1991.

The Strode’s Foundation is a registered charity and provides support to the College, including a substantial capital contribution to the Tercentenary Building, its Courtyard and the Student Centre and funds for a variety of College needs. It supports the Strode’s Foundation Academic Achiever’s Award and assists with hardship through the Strode’s Foundation Support Fund. The Foundation is the owner of the land on which the College stands and most of the buildings. The Foundation’s nine trustees include two who are nominated by the Coopers’ Company, one by Royal Holloway and Bedford New College and one by Runnymede Borough Council, besides five others who are elected by the Foundation.

Strode’s College and East Berkshire College formally merged on 9 May 2017 to create a larger college group under the name, Windsor Forest Colleges Group.

References:

Henry Strode’s Charity 1704-1994, Pamela Maryfield

The Strode Foundation 1704-1954, Strode’s School Governors