Just Williams Part 3 – some of the Victorian tradesmen who shaped Egham High Street

Margaret C Stewart

Over the last few years we have seen many of the businesses in Egham High Street close – and welcomed new ones. Even without a pandemic these frequent changes are not unusual but it is always pleasing to see how some businesses stay for years, often under family management. This short series of articles looks at some of the businesses which began trading in Egham during the Victorian era and continued for over 50 years. What they have in common is that they were all begun by men called William…

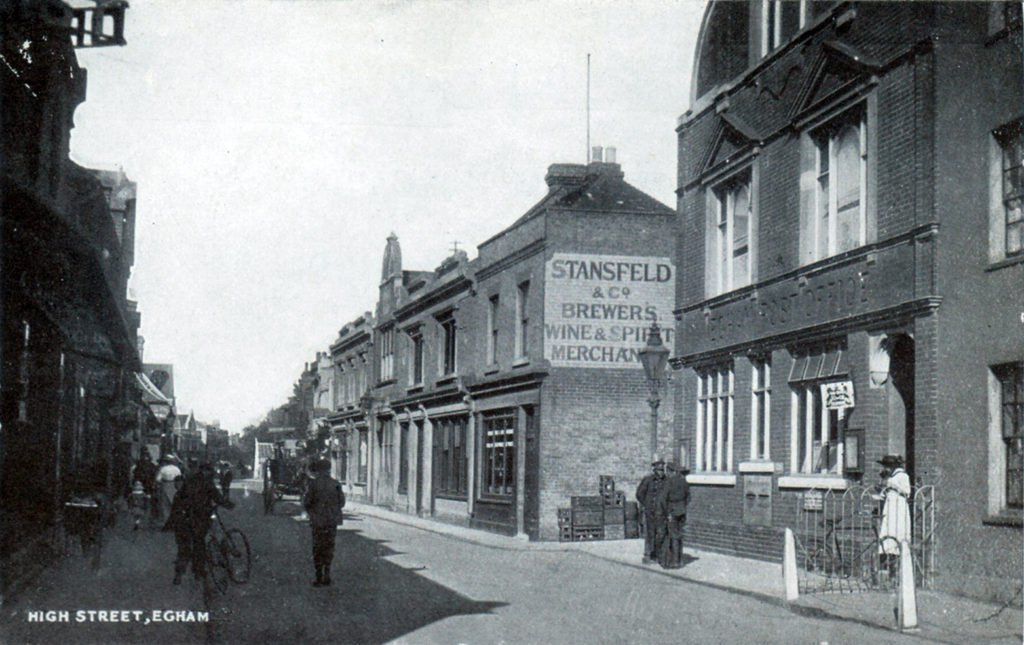

3. Three generations of William Gardeners, ironmongers (and more) 59 High Street.

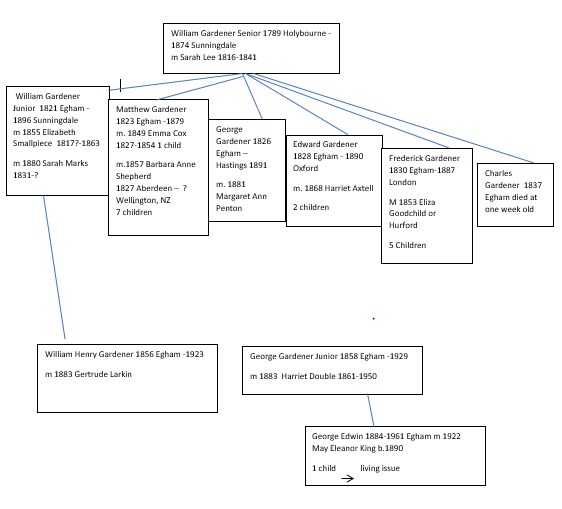

It was not uncommon for Victorian men to name their oldest son after themselves, but the Gardener family of Egham took this to new heights – for three generations they named the eldest son William and another son George! To avoid confusion in this article I have added the suffix Senior, Junior or Henry as indicated in the family tree below.

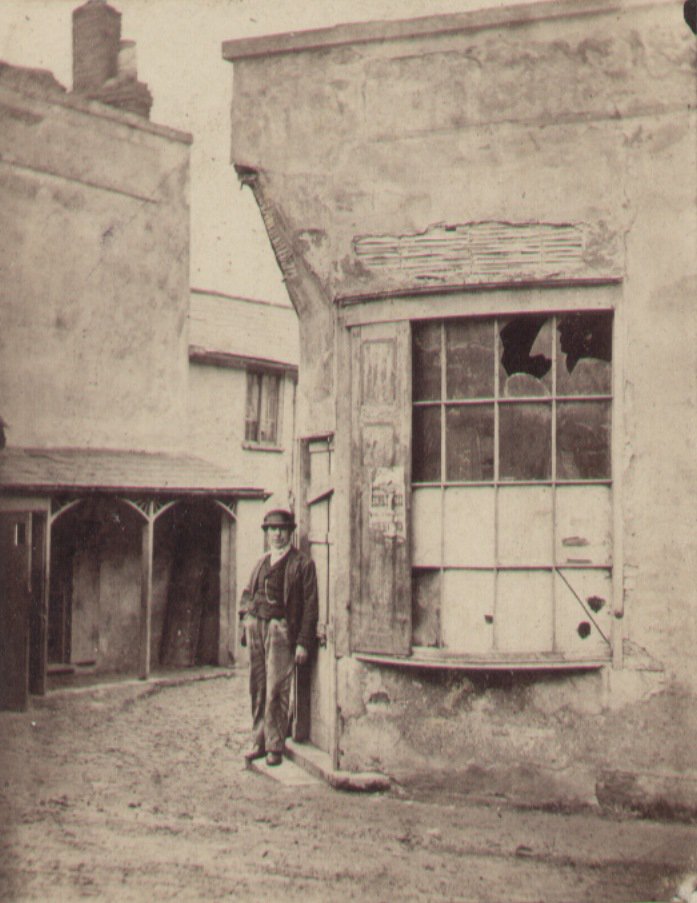

William Gardener Senior moved to Egham with his wife from Hampshire in the early 1820s. Their first son, William Junior, was born in Egham in 1821, followed by five other boys. William Senior set up in business as a brazier and iron monger and, in 1823, he bought a messuage at 59 High Street to open a shop. Messuage is an Anglo-French word meaning a dwelling house with its outbuildings and adjacent land. [i] This definition is confirmed by an 1864 description of the property as a house, formerly two tenements, and a workshop and garden. He was to continue working there until 1871.

Most of his sons followed in his path and trained as ironmongers, blacksmiths or whitesmiths [ii]. William Junior, George and Matthew were working alongside their father at no 59 by 1841.

There was clearly more than enough work for more than one ironmonger. After William Junior married in 1855, he opened his own shop at 83 High Street while his brother George remained in partnership with their father. He also invested in property, acquiring cottages in Post Boys Row, which he rented out, and the Royal Standard pub at 148 High Street.

He was able to send his sons away to Cranleigh School, which opened in 1865 primarily as a community school for the sons of local farmers.

By 1851 Matthew Gardener had moved out of the area and opened his own ironmonger’s business in Odiham. His life was to take a tragic turn. His first wife seems to have died while their only daughter was very young – and she was sent away to be cared for by others, eventually taking up a life in service. Matthew and his second wife Barbara had seven more children together and decided to emigrate to New Zealand. They must have taken ship in late 1878 or early 1879 on the SS Halcione which was used for emigrants requiring a cheap passage. Sadly Matthew died during the voyage, of dropsy[iii] in June 1879, leaving less than £300 to his widow who then settled in Wellington.

Edward Gardener did not follow the family path: instead he became a printer and may possibly have worked for William Larkin at No 60 while he was still living in the family home. By 1861 he was in Brighton but this was only temporary. By 1871 Edward was married and running the Chequers Inn in Oxford. He died there in 1890.

After a short time working with his father and brothers, the youngest surviving son, Frederick Gardener, moved to London where he ran a business as a whitesmith from at least 1861 until his death in 1887.

William Senior seems to have retired shortly after 1871 and moved to Fir Cottage in Sunningdale where he may have continued offering ironmongery services. William Junior moved his business into No 59, later to be joined by his sons, William Henry and George Junior.

George, who had worked alongside his father even as his brothers formed their own businesses, now followed Edward’s career path. By 1871 he too had moved to Brighton as a printer and lithographer. It is tempting to assume that they worked there together before Edward went into inn keeping. George married fairly late in life and he and his wife Margaret were to stay in Sussex even after he retired, He died in Hastings in 1891.

When William Senior died in 1874, William Junior moved to Fir Cottage and continued to work from there (until his death in 1896), leaving the teenage William Henry and George Junior in charge at No 59. They were clearly enthusiastic and seem to have installed a new frontage to the shop in 1879 (possibly as part of a general refurbishment of the property) incorporating William Henry’s initials – the remains of these initials are still visible today.

However, it is likely that that their father still owned the shop: when they completed their entry for the 1881 Census, instead of either of them claiming to be Head of Household, both William Henry and George Junior described themselves as Son but William Junior was living at Fir Cottage. In 1881 a William Gardener bought 155 High Street opposite the shop. It is not clear whether this was William Junior or William Henry but later events make it most likely to have been the latter. William Junior’s investments in property had taken place around the year 1866: these properties were left jointly to his sons when he died in 1896.

Both brothers married in 1883. William Henry wed Gertrude Annie Larkin, daughter of the printer William Larkin, who was based next door at No 60. William Henry and Gertrude spent the first years of their married life living above the business at No 59. In 1895 they moved across the road to 155 while keeping the business at 59. They had no children.

George Junior married another local girl, Harriet Double, and they moved to Station Road, into a house which may have been the property of her father, John Double. William Henry began to expand his career in 1882 when he took on the role of Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths for the Egham District. George Junior served as his Deputy.[iv]

From February 1885 he added to his registrar duties the task of running the country’s first labour exchange[v] at No 59 offering his services on a voluntary basis. He was primarily involved in finding work for builders etc who had been working locally in construction projects such as Holloway Sanatorium and Royal Holloway College. This labour registry was the brainchild of local resident and philanthropist Nathaniel Cohen who wrote that “much of the success of the Egham registry was due to the local registrar, Mr W.H. Gardener, who was well acquainted with the district and very eager to help applicants… The situation of the registry was less important than the choice of the right man to act as registrar.”[vi]

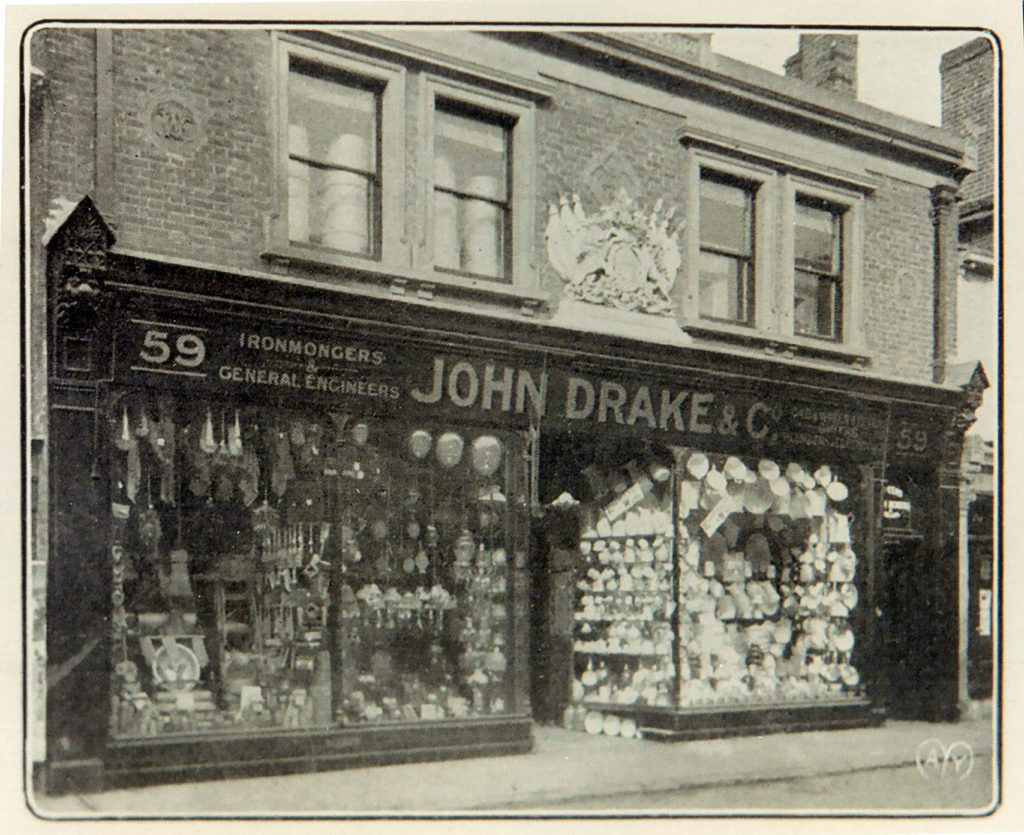

The Labour registry closed in 1894 when employment in the area was harder to find and the scale of work had grown to such an extent that it was beyond the scope of a voluntary organisation. William Henry and George Junior continued to run the ironmongery at No 59 until at least 1901 when they sold the business to Devon-born John Drake.

After giving up ironmongery William Henry took on the job of sub-postmaster in addition to continuing as registrar of birth and deaths for the Egham district, turning No 155 into the Egham Post Office but still living upstairs until at least 1918.

George Junior continued as his Deputy for a few years but by 1911 had embarked on a new career as a coal merchant.

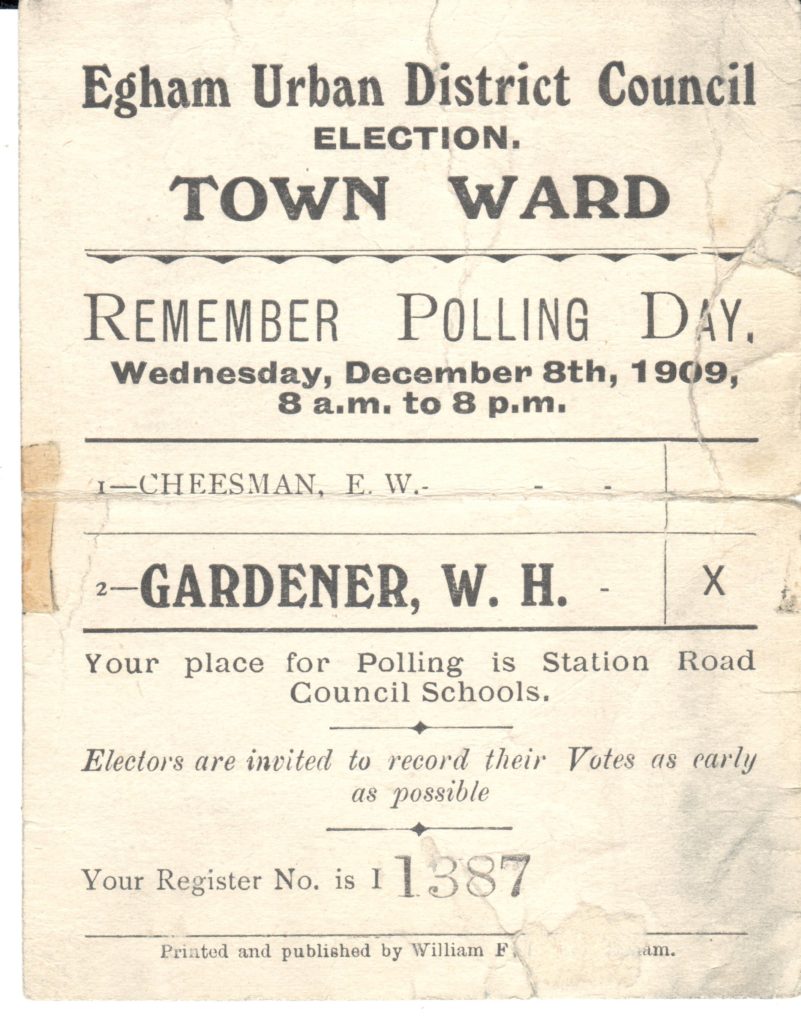

The brothers both played a part in local politics. George served on the Rural District Council (RDC) from 1901. When the RDC became Egham Urban District Council (EUDC) in October 1905, it was William Henry’s turn to stand for election. He served as a councillor from 1909-1916.

Amongst his duties was congratulating local dignitaries Baron and Baroness de Worms on their Golden Wedding Anniversary in 1910. W H Gardener is the man standing on the right of the picture.

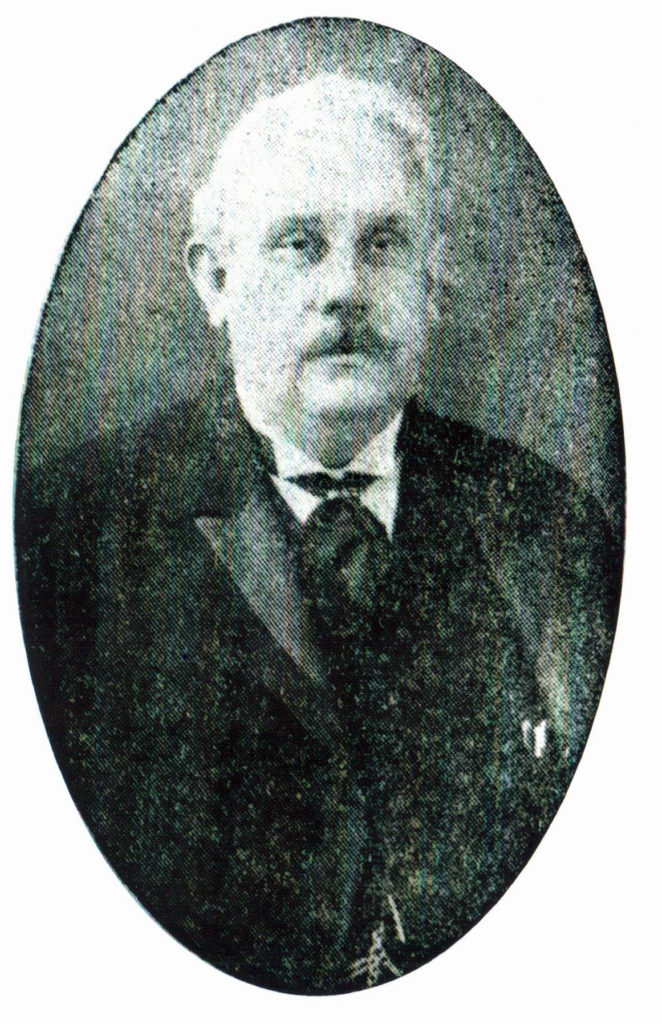

After he was re-elected in 1915, the local newspaper carried his photograph (P4455) – it shows a rather serious looking man but a letter in Egham Museum describes him as “well-known for his mischievous ways!” Like many other Victorian businessmen, including his brother-in-law Edward Budgen (married to Gertrude Gardener’s sister), he gave generously to local charities including in 1905 to the Egham Cottage Hospital.

William Henry seems to have retired in 1921 and a Miss Barrett took over the Post Office. At about this time he acquired No 153 High Street, next door to the Post Office and home of the Bohemia Cinema (later the Savoy). He moved to 5 The Avenue where he died in January 1923. His estate of £6899 3s 8d, left to his widow Gertrude, would be worth £435,730.78! – not bad for a third-generation iron monger.

George Junior died in 1929 when he was living at Rose Cottage Egham. He left £2805 (£198,060.57) to his widow Harriet. His son George Edwin, pictured below, became a railway clerk and did not enter the ironmongery business. His descendants now live in Canada.

From 1921-1962, 155 High Street, perhaps fittingly, became the property of EUDC, and the ground floor was used as offices.

John Drake and his descendants continued to run the ironmonger’s at No 59 until 1951.

No. 59 is now home to Timpson’s; the building at No. 155 was amongst those demolished in 1966-67 to make way for The Precinct. No. 37 The Precinct, on this site, was in turn removed in 2014 to create a new access route to Waitrose.

General sources: Egham Museum photograph and document collections (including ratebooks),

https://www.ancestry.co.uk , https://www.findmypast.co.uk

[i] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/messuage [accessed 13.9.22]

[ii] Whitesmith was another name for a tinsmith or, alternatively, a worker in iron who finishes or polishes the work. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/whitesmith [accessed 22.9.22]

[iii] old name for fluid retention, commonly caused by heart failure

[iv] Although contemporary directories refer to William Henry as registrar he was actually a sub-registrar. For purposes of recording births and deaths, the country was divided into Poor Law unions with the superintendent registrar’s job usually taken by the Clerk to the Board of Guardians of the Poor Law union. The actual work was done by registrars of births and deaths operating within a sub-district. Additionally there was one registrar of marriage for each district. Neither they nor their deputies were salaried but received pay according to the number of events that they registered and certificates that they issued and sometimes other duties. https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/early-civil-registration/ [Accessed 8 Sept 2022]

[v]Egham’s pioneering labour exchangehttp://eghammuseum.org/labour-exchange/ [Accessed 22 September 2022]

[vi] Campling, P.J (1973) Nathaniel Cohen and the beginnings of the labour exchange movement in Great Britain IN Harrison, E.E., honorary editor, Surrey Archaeological Collections: relating to the history and antiquities of the county. Vol. 69. Guildford: The Surrey Archaeology Society p.155-167