Perfume: SHEM-EL-NESSIM — the scent of Araby?

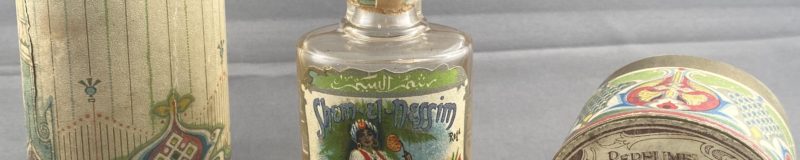

This object (Object MC34) is a perfume bottle with outer packaging, which was produced by J. Grossmith and Son of London, a long-running perfume company which was created in 1835. The company was dissolved in 1980 but has recently been revived by the descendants of the original owners. During the 19th century, they enjoyed royal warrants in Britain, Greece, and Spain and were worn by nobles and royalty from across Europe.

Perfumes have been used by humans since ancient times. They used to be and perhaps still are symbols of wealth, nationalism, religion, and status, and of course, they serve the purpose of masking the problem of body odour. At the beginning, perfumes were made using spices or real flowers, which means they tend to be less affordable and accessible. During the Victorian era, advancements in the field of chemistry and technology allowed skilled perfumers to recreate the scent of several flowers using certain chemicals, creating a synthetic scent to use in their perfumes.

According to the Grossmith company website, this fragrance was first created in 1906 and was named “Shem-El-Nessim”, which in Arabic means ‘smelling the breeze’. This would have been a perfume available at high-end department stores, catered for the upper classes, as the perfume was largely made of natural ingredients like rare flowers and spices, instead of synthetic ones.

The bright colours of the perfume bottle and outer packaging was designed to be eye-catching and clearly drew inspiration from Middle Eastern art and decoration. It is believed that the heavy emphasis on the packaging was due to the growing competition for customers at the high-end fragrances market at the start of the 20th century.

The company marketed this perfume as ‘the scent of Araby’. In the mid-19th century, it was common that perfumers create scents based on the nature, such as scents that were created to smell like a trip to the Alps. Grossmith London also contributed to this trend in the 1880s, by releasing perfumes such as “Hasu-No-Hana” (1888), which means “Lotus Flower” in Japanese, and ‘Phul-Nana‘ (1891), which is “Lovely Flower” in Hindi. It is clear from their names that these perfumes were designed to emulate the smells of exotic lands.

This perfume provided its wearers an opportunity to ‘escape’ into a world of exotic adventure through smell, which would have been even more appealing to those who were unable to travel . The use of Arabic at the top of the bottle from our collection reinforces the perfume’s exotic appeal, as not many people would have been able to read Arabic. It also adds an element of mysticism surrounding both the perfume and the landscape that it is meant to represent. Advertising campaigns promoting this perfume are themed around Egypt, which was controlled by British forces when this perfume was created and sold.

At this time, parts of the Middle East and Asia were heavily romanticised and seen as exciting and unpredictable environments, particularly by individuals back in Britain. Much of this was tied to British imperial ideology and conquest. While we may see items like these as problematic and discriminatory, Empire was openly celebrated in Britain and was a point of pride for many communities.

The women seen on the front of the perfume bottle is a racist stereotype of Arabic women, who were seen by British people as promiscuous. Remarkably, this same perfume scent can still be bought today, yet the packaging no longer features the Arabic text, or the lady seen on the front of the original bottle.

BUT WAIT … why is it in our collection then?

Katie Smith

Further Reading

‘HASU-NO-HANA’, Grossmiths London, <https://www.grossmithlondon.com/hasu-no-hana-1> [accessed 2nd January 2022].

‘PHUL-NANA’, Grossmiths London, <https://www.grossmithlondon.com/phul-nana-1> [accessed 2nd January 2022].

‘Shem-El-Nessim’, Grossmith London, <https://www.grossmithlondon.com/shemelnessim-1> [accessed 18th November 2021]. ‘Heritage: J. Grossmith & Son’, Grossmith London, <https://www.grossmithlondon.com/heritage-j-grossmith-and-son> [accessed 18th November 2021].

‘SHEM-EL-NESSIM’, Grossmiths London, <https://www.grossmithlondon.com/shemelnessim-1> [accessed 2nd January 2022].

‘THE VICTORIANS: FROM VIOLET POSIES TO VA-VA-VOOM’, The Perfume Society <https://perfumesociety.org/history/the-victorians-from-violet-posies-to-va-va-voom/> [accessed 16th December 2021].

Dugan, Holly, The Ephemeral History of Perfume: Scent and Sense in Early Modern England (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Ellie Pithers, ‘Grossmith: scent by descent’, The Telegraph, 13th May 2013, <http://fashion.telegraph.co.uk/beauty/news-features/TMG10054361/Grossmith-scent-by-descent.html> [accessed 2nd January 2022].