Picturing Egham – Part 1

Egham has always been quite picturesque. Embraced by green fields and historical landmarks, Egham and its surroundings have been ideal subjects for artists across centuries. Both local and visiting artists have been committed to eternalising Egham’s beauty through their art.

This online exhibition places women artists and their works at the forefront of this artistic interest in Egham. Through their art, these women take the role of tour guides as we embark on a pictorial journey across time, exploring the buildings, events, and locations which reveal the importance of our local community.

The exhibition is divided in three parts, each focused on a different period. Through the discovery of the museum’s artistic collection, we look at depictions of local scenes by women artists to further understand our local history and how it reflects the social and artistic developments of each period.

Art and Nature

Although Surrey only officially became an ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’ in 1958, its reputation as such began much earlier on. The resurgence of landscape art as a dignified artistic genre in the 19th century led to many artists travelling across the country to portray Surrey – and, subsequently, Egham – in their works.

George Delamotte, Ankerwyke Priory and Yew Tree, Lithograph (date unknown)

Credit: Egham Museum PR6a

Thomas Rowlandson, A Fishing Party near Magna Carta Island, from Runnymede, Pen, Pencil, Brown and Gey Ink, Watercolour on Paper (date unknown)

Credit: Egham Museum PR48

Unknown Artist, Fishing Temple on the Lake at Virginia Water, Lithograph (date unknown)

Credit: Egham Museum PR64

John Serres, Virginia Water Lake, Watercolour on Paper, 1825

Credit: Egham Museum PR275

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were challenging for women artists. Although some women succeeded with the help of relatives or friends who either supported their artistic endeavours, or were artists themselves, the social expectations of women did not always enable their full success as ‘professional’ artists. Important institutions for the artists’ visibility, such as the Royal Academy of Arts, were not so keen on accepting works by women at this stage. Moreover, there were certain genres which were seen as more suitable for a lady – still life, flower-painting, and, indeed, landscapes – which limited their recognition as artists equal to their male peers.

This is where the artistic practices of Harriet Gouldsmith (1787-1863) and Emily Waldegrave (1788-1870) come into play. Although they differ in career development, artistic techniques, and even scenes portrayed, they are placed side by side in our collection as two women artists depicting landscapes of Runnymede in the early Victorian period.

Mysterious Islands

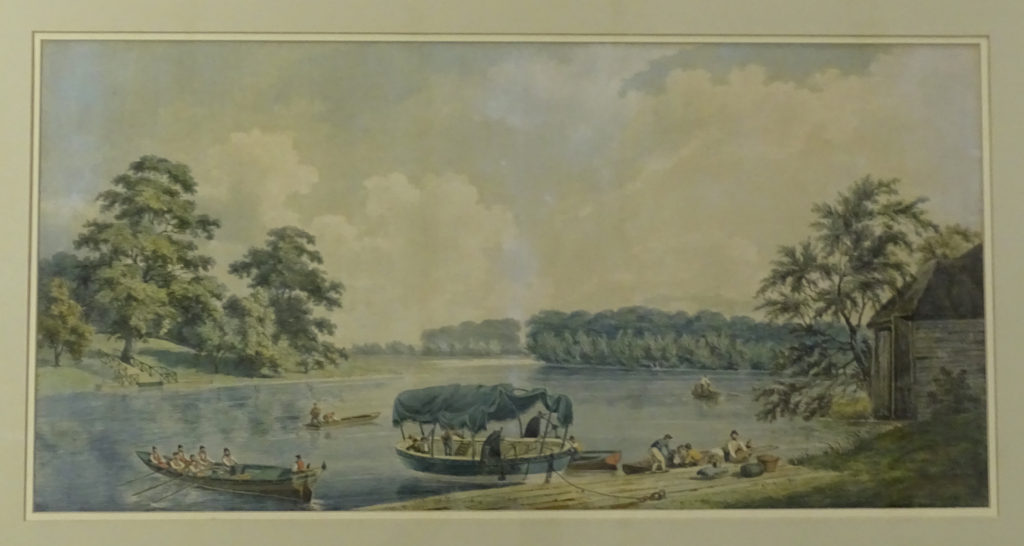

This is one of two of Gouldsmith’s works which portray a local landscape. At this point, she had already established herself as a well-known landscape artist, becoming one of the few women to achieve such status at this period. Her success is evidenced in her exhibiting record: between 1809 and 1855, Gouldsmith displayed over 200 artworks in institutions such as the Royal Academy, the British Institution, the Society of Painters in Oil and Watercolour, and the Society of British Artists. Despite her achievements, her later years were not as successful due to financial difficulties. This led Gouldsmith to seek help from friends, and to receive charitable donations from the Royal Academy until the year before her death.[1]

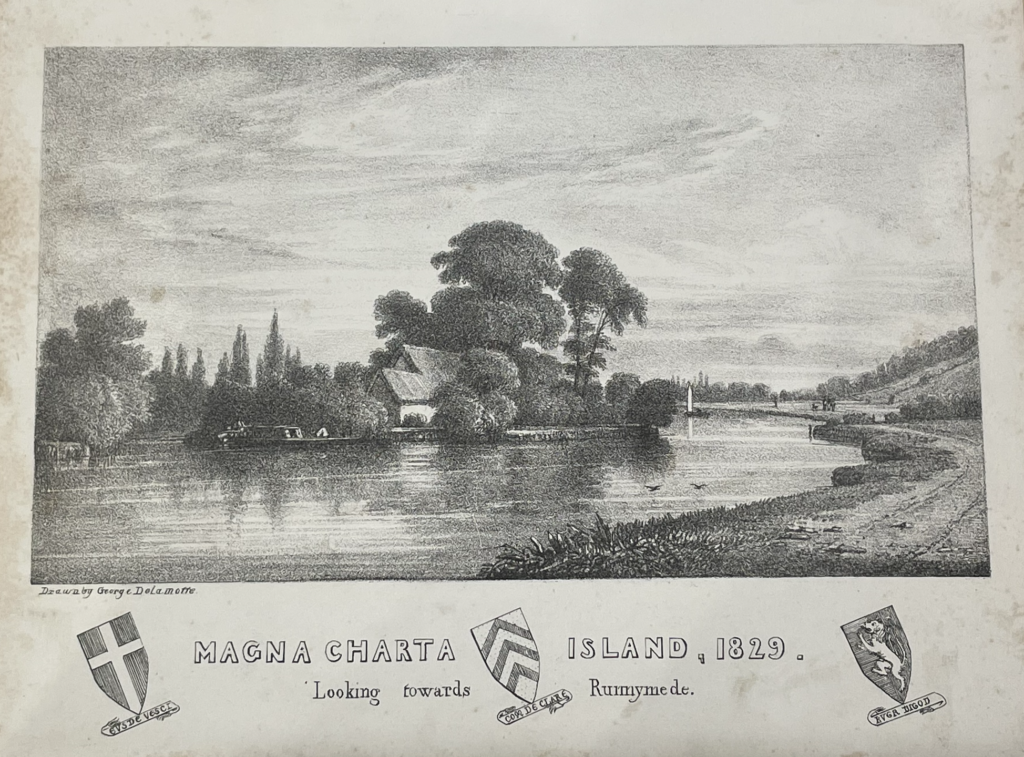

The above painting depicts Magna Carta Island, located on the reach above the Bell Weir Lock in Egham. This work reflects one of the most popular tourist attractions of Runnymede at the time. Many visitors used to cross the river by boat to visit the island where allegedly the stone on which the Magna Carta was sealed in 1215 was located. The ‘Charter Stone’, as it became known, was said to be found in the Thames in the early 19thcentury.

The rumours surrounding this island were, however, untrue. Although the Magna Carta was, in fact, sealed on the banks of the Thames at Runnymede, this did not take place on the island. The misconceptions about the stone and the island’s association with the Magna Carta date back to the early 18th century, and were further repeated in historical descriptions of the area across the 19th century.[2] In 1834, Mr George Simon Harcourt, Lord of the Manor of Wraysbury and High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, constructed a stone house on the island, and built a room specifically to accommodate the ‘Charter Stone’, which increased the false claim that this was, in fact, the stone associated with the Magna Carta.

It is possible these early views were confusing the sealing of the Magna Carta with the sealing of a charter between Prince Louis of France and the Early of Pembroke, which did take place in the area in 1216.[3] While the mystery is now solved, these accounts serve to illustrate the social and historical meanings of Gouldsmith’s subject.

The depiction of the river is not only allusive to the tourist attraction of the area, as it is also indicative of the importance of the local resources for the local communities. Indeed, fishing was an important activity for the people of Runnymede. Gouldsmith’s River Thames with Fish Weir further exemplifies this. This depiction includes an open timber frame in the river. This was used as a fishing weir with suspended eel traps of basketwork, which were lowered into the Thames.

Credit: Egham Museum PR77

Another mystery surrounding Goulsdmith’s depictions of the Magna Carta Island is the works’ exact dates of production. While it has been stated that River Thames and Magna Carta were painted in 1840 and 1845, respectively, it has been argued that they depict the same precise location of the island: Magna Carta depicts the island before the construction of the stone cottage in 1834, and still with a thatched cottage in its place; and River Thames portrays the island after the thatched cottage was replaced with the stone cottage in 1834.[4]

This engraving by George Delamotte (1788-1861) gives reason to the later view. The thatched cottage is here depicted as being part of the island in 1829. Additionally, historical descriptions of the river alongside the island seem to verify the existence of a fish weir.[5] This would then confirm the theory that the paintings portray the island at different stages.

Enchanted Forests and Ancient Ruins

While Gouldsmith has started to be recognised for her artistic achievements, Emily Susanna Laura Waldegrave’s life is still in obscurity. Born in 1788, she was the daughter of Admiral William Waldegrave, 1stBaron Radstock and Castle Town (1753-1825), and Cornelia Jacoba van Lennep (1753-1839). In August 1815 she married Nicholas Westby (1787-1860), who came from a noble lineage, and they had at least two children – Horatia and Caroline. Emily Waldegrave died in 1870, and was buried at Highgate Cemetery, in London.

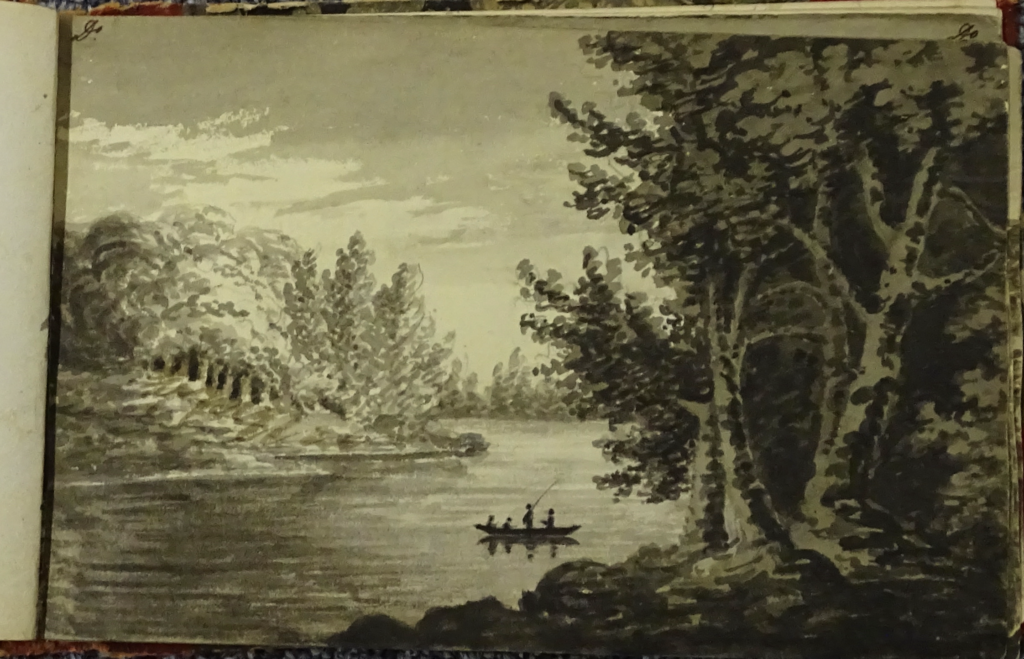

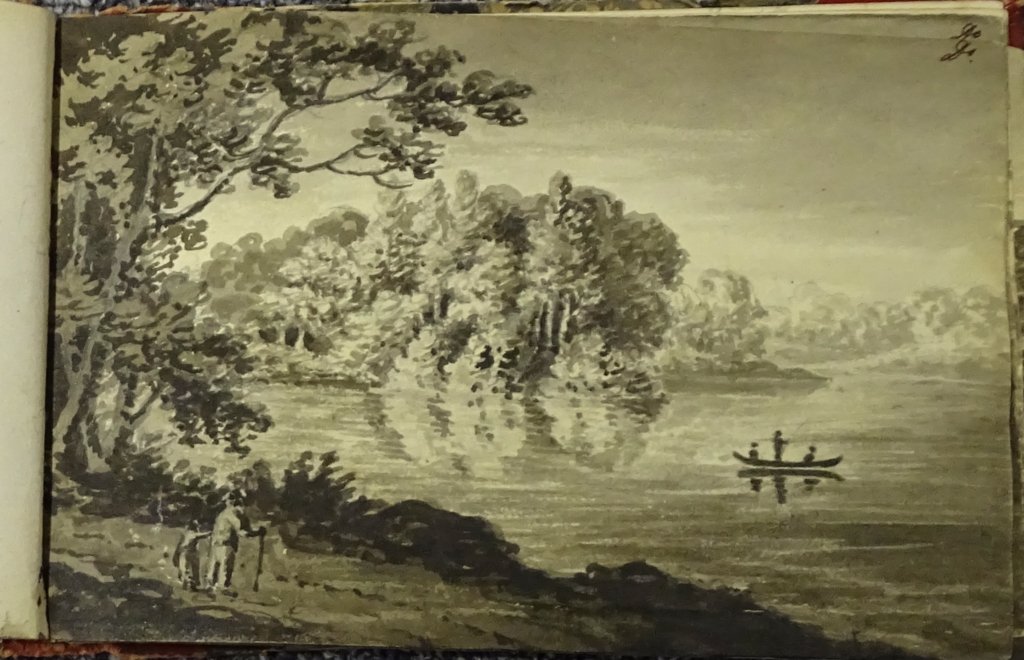

Credit: Egham Museum PR38

Apart from Waldegrave’s sketchbook in our collection, there are very few public references to her art. Two of her drawings – View of Arundel Castle (1810) and View of Windsor Castle (1811) – were sold at the auction of the collection belonging to the Earl of Waldegrave at Strawberry Hill, in 1825.[6]

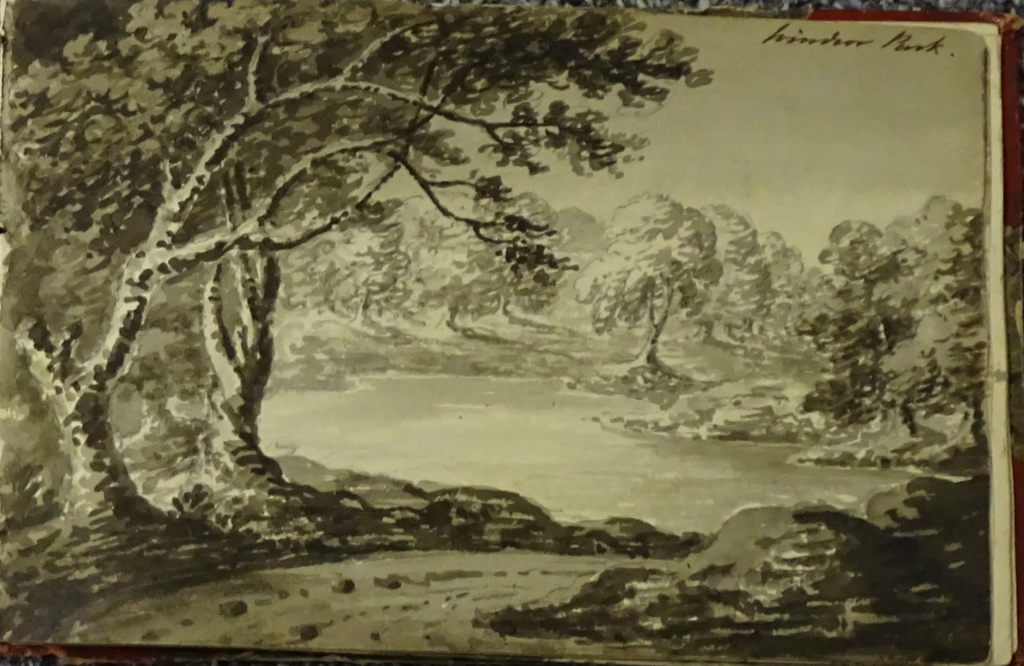

Although the whereabouts of these two works is now unknown, the drawings of Windsor Great Park and Windsor Castle in her sketchbook give us a glimpse of her artistic abilities. Waldegrave clearly had an artistic interest in castles and monuments peeking out amidst landscapes. Her sketches of natural scenes from Virginia Water to Windsor Great Park are illustrative of this.

Credit: Egham Museum PR38

Flipping through Waldegrave’s sketchbook gives us more than a reflection of how these landscapes looked like at the time. Viewing both finished and unfinished sketches side by side allows us to witness Waldegrave’s artistic process. While the works completed with ink reveal the density and magnitude of flora in the scene, her pencilwork shows the foundational layer of the landscape.

Waldegrave’s unfinished sketch above matches the incompleteness of the subject: ruins partially forming the Temple of Augustus at Virginia Water.

The ruins allude to the issues of colonialism and imperialism of the period, as they were not, in fact, erected by Romans in Britain. The stones were brought from Libya in 1816 by the British officer Hanmer Warrington (c.1776-1847), who was marvelled at the magnitude and history of the ruins of what was once the Severan Basilica of Leptis Magna, built by the Emperor Septimius Severus (141-211).

Upon arrival, the stones stayed in the British Museum until 1826, when King George IV’s architect, Jeffry Wyatville (1766-1840), decided to build a decorative monument in the surrounding area to Windsor Castle.

The ruins did not go unnoticed by engravers and artists – including Waldegrave – who did not hesitate to register the moment in their depictions.

Similar to Goudlsmith’s, Waldegrave’s depictions also give us insight into the practices of the local community. The below sketch emphasises the importance of the Thames for the residents of Runnymede as the source of fish for the community.

This sketch depicts a boat on what is today known as the Virginia Water Lake. The lake was formed as a result of the damming of the Virginia River. In 1768, the dam burst, and it was replaced by the current cascade in 1789.[7]

There have been occasions when the lake has been drained, including during the Second World War, when it was regarded as a possible enemy navigational aid.[8]

Reading into the artworks of Gouldsmith and Waldegrave gives us a glimpse of not only how our neighbouring landscapes looked like at the time, but also how their perception and history have developed across time.

Read Part 2 of Picturing Egham here.

References

[1] Kathryn Moore Heleniak, ‘Money and marketing problems: The plight of Harriot Gouldsmith (1786-1863) a professional female landscape painter’ in The British Art Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2005, pp. 25-36, pp. 26-31 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41614644

[2] DOC2938, Egham Museum

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] George Robins, Catalogue of Contents at Strawberry Hill Collected by Horace Walpole, Sale of 25th April 1852

[7] DOC2940, Egham Museum

[8] Ibid.

Further reading

Harriet Gouldsmith, A Voice from a Picture (London: John Booth, 1839) https://archive.org/details/avoicefromapict00voicgoog/page/n17/mode/1up?view=theater&q=magna

Paul Cooper, ‘How Ancient Roman Ruins Ended Up 2,000 Miles Away in a British Garden’ in The Atlantic, 2018 https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/01/roman-ruins-windsor-castle/550199/