‘Riots, Rogues and Rebellions’…Where to Start?

Issie Davis

I approached the strapline of Egham Museum’s upcoming exhibition, ‘Riots, Rogues and Rebellion: Activism in Egham’ from the perspective of a History undergraduate, familiar with these categories of protest and their use across the past’s headlining acts of defiance, but unused to looking at the concept of resistance in any detail.

My task would, I presumed, be one of piecing together “riots”, “rebellions” and “roguish” characters across the district’s history, exploring their causes, aims, and outcomes to gauge the temperature of local dissent.

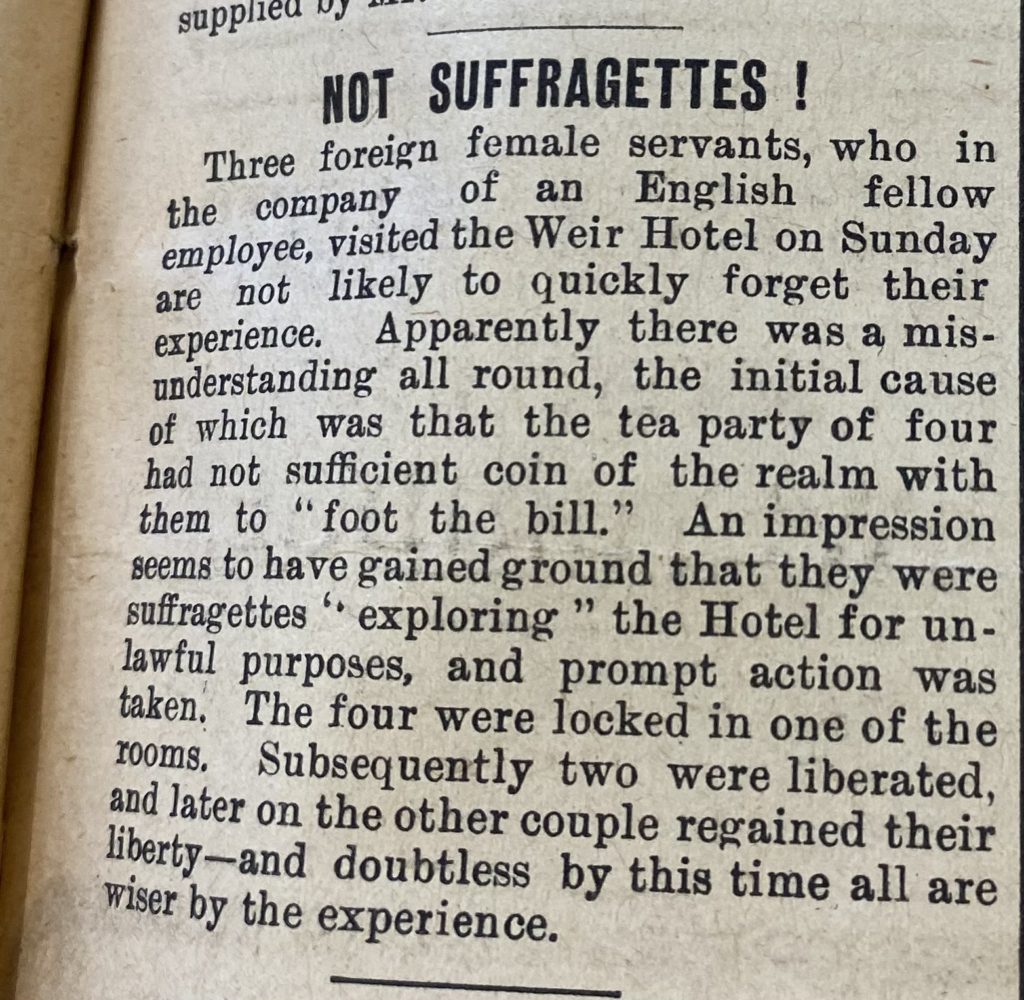

My starting point was the Suffragettes – a group I knew, from their associations with Royal Holloway, had cultivated unrest in the area. I began by chasing up whispers of disturbance in the early 1910s; Isabel Cowe being stopped by a policeman in 1912 for riding her bicycle on an Egham footpath during the final leg of a Suffragette Pilgrimage from Edinburgh and the closure of the Picture Gallery following a warning of arson on houseboats on the Thames. This introduced me to the frustrations and rewards of archival research. I would often follow up the findings of a colleague, scour sources with different priorities to mine, but find nuggets of valuable, startlingly candid information along the way, which offered me a better feeling for the time than any academic book could. A seemingly unremarkable piece from the 1913 Surrey Herald entitled “Not Suffragettes” revealed an anxiety surrounding feminist violence I never knew existed. After struggling to foot the bill at a hotel in Walton-on-Thames, three female servants caused “a misunderstanding all round” when they were suspected of being WSPU militants scouting the site as a future protest venue and detained in hotel rooms until police arrived and determined their innocence.

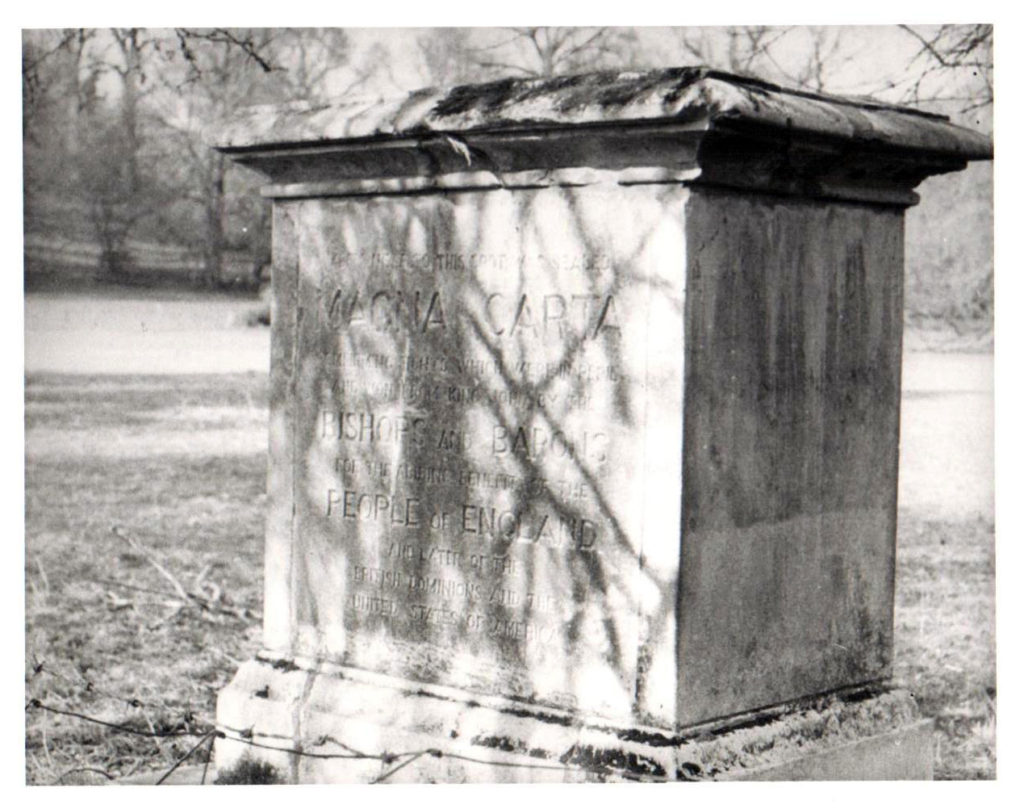

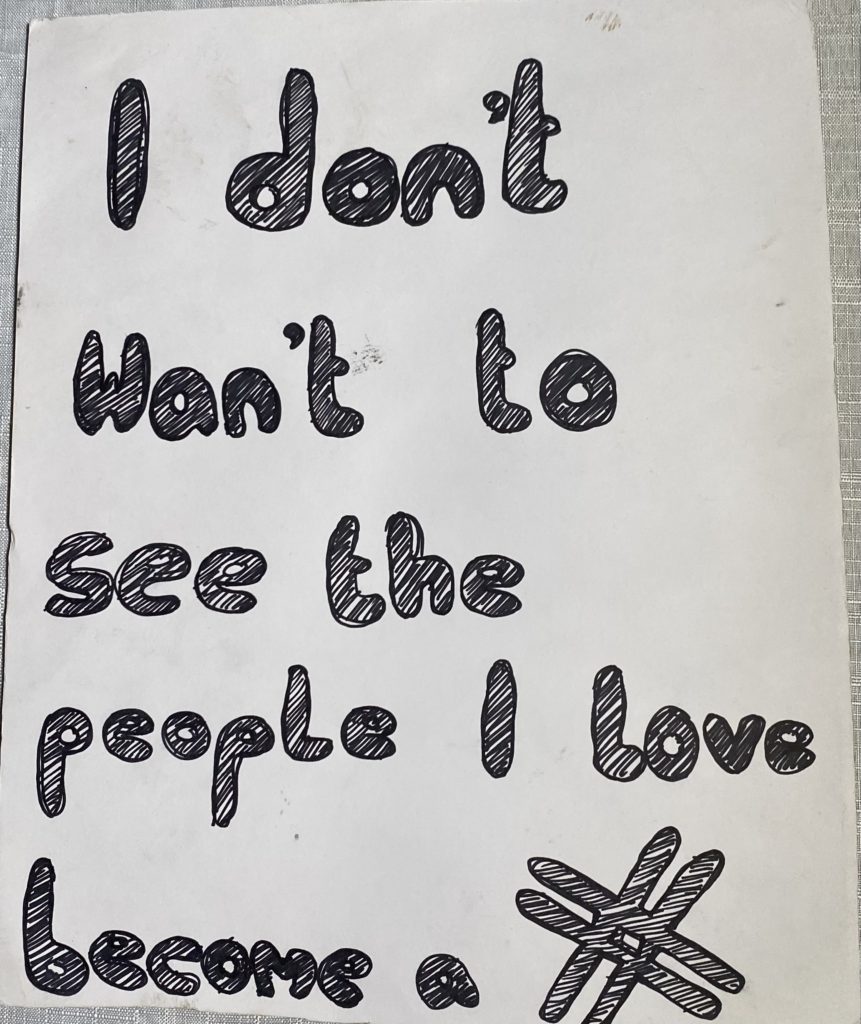

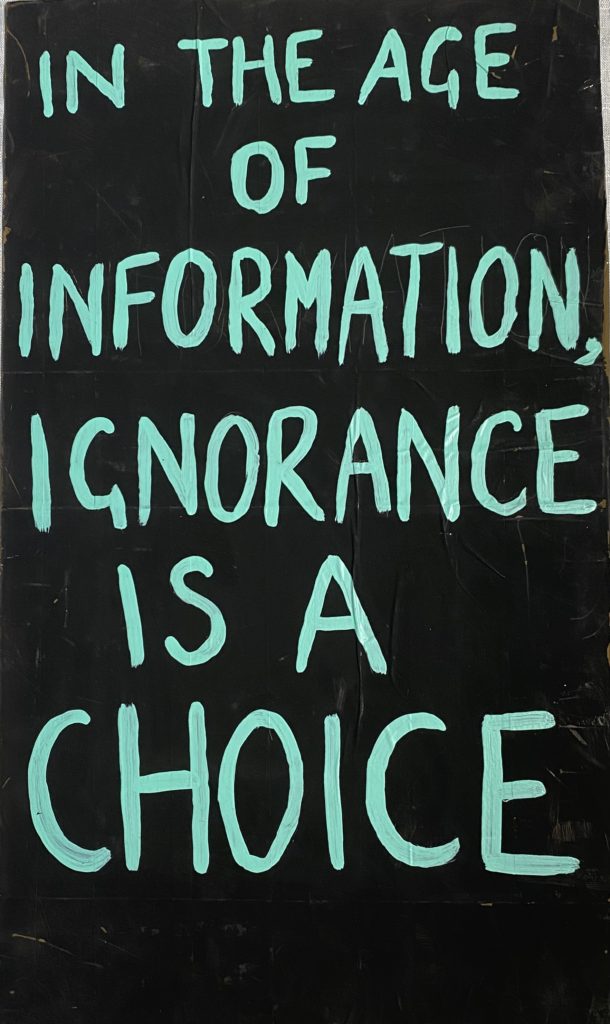

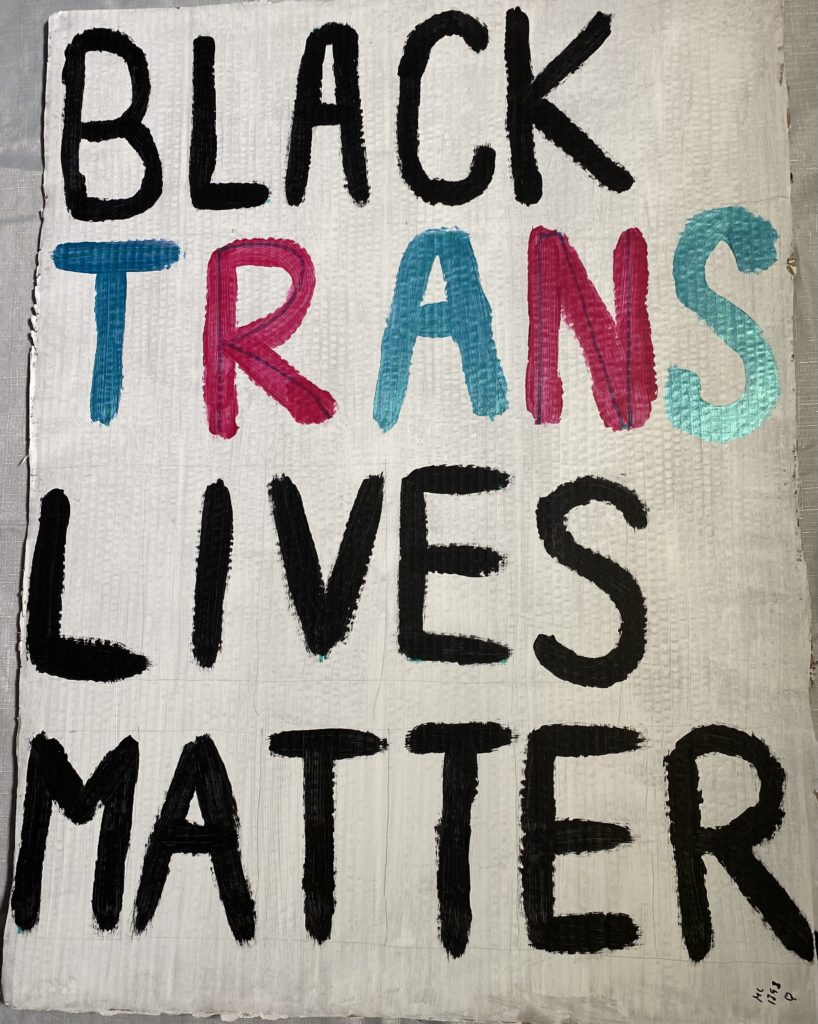

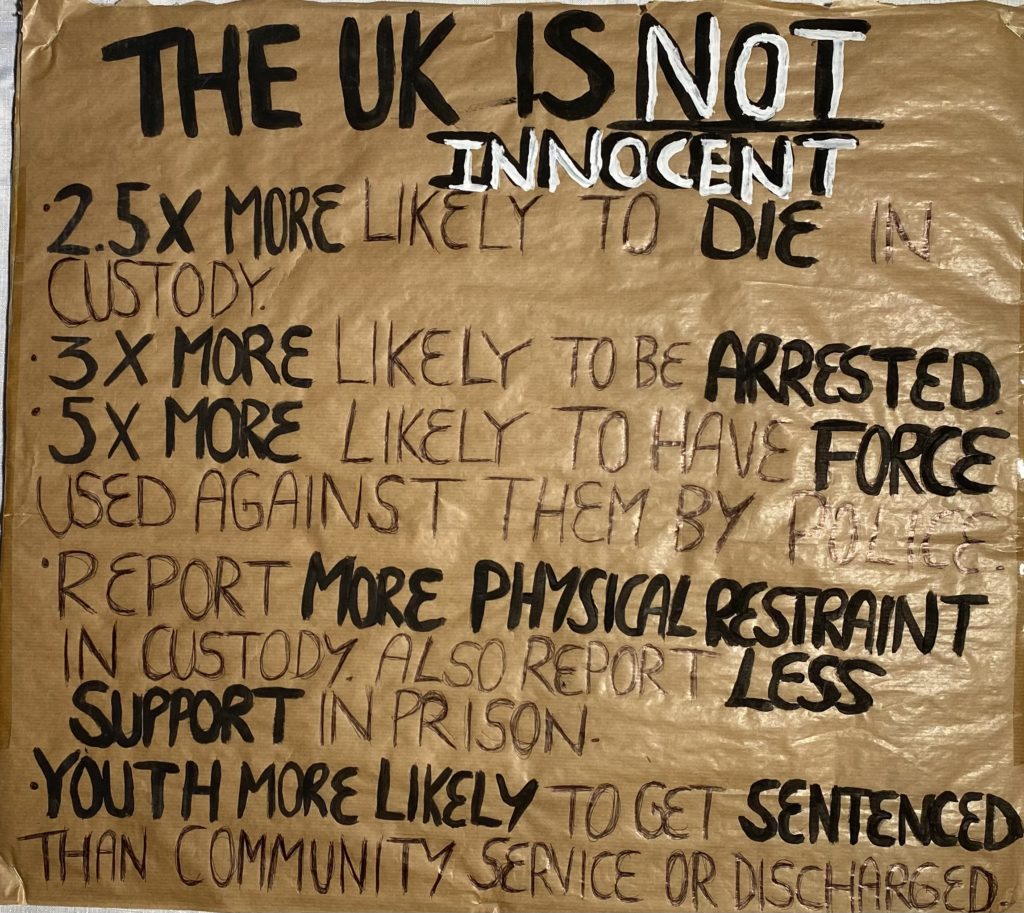

I soon compiled a collection of happenings across a staggeringly long period of time, spanning from Boudica’s final revolt in AD 61 (possibly taking place at modern-day Virginia Water) to the rebellion of the barons precipitating the sealing of the Magna Carta in 1215 and the role of Egham men in suppressing colonial rebellions of the 19th century to the decidedly peaceful Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests making headlines today.

I was initially daunted by handling such a vast swathe of the past. The ‘rebellions’ each highlighted different concerns (territory, politics, agriculture, religion, gender, race and the natural environment) and, through comparison, threw up more questions than they answered. Why, for example, did Boudica’s tribesmen ‘revolt’ and King John’s barons ‘rebel’?, what makes an agrarian rising in the 19th century different from one in the 14th?, why do some rebellions qualify as expressions of activism and others are deemed as menaces to society? And how does proximity to dissent affect our interpretation of it?

In seeking answers I came to appreciate that rebellions, like so many aspects of History, are more authentic as constructs of memory rather than realities. This is where the real interest in studying them lies. The way we remember and commemorate non-compliance holds up a mirror to society today. We downplay the rebellion behind the production of the Magna Carta to avoid tainting its significance as a cornerstone of today’s political liberties and we situate the Suffragettes within an aesthetic of marches and “votes for women” banners as opposed to violence and vandalism to maintain their respectability as pioneers of contemporary women’s rights.

Meanwhile, we conceal a possible attempt for Indian independence under the guise of military disobedience to avoid facing the horrors of British Colonialism and, in an age of factory farming and genetic modification, we downright forget the women and men who fought against the terrifying prospect of machines taking over their jobs. Clearly, not all Egham riots, rogues and rebellions stand equal in public memory. Churchill’s statement, History is “written by the victors”, is still relevant today.

The upcoming exhibition offers an exciting opportunity to examine diverse forms of opposition alongside each other, give a platform to lesser-known developments such as the Thorpe War, and ask some of these important, if uncomfortable questions. As the recent Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion Protests demonstrate, protest is not going away any time soon. Be it in the 1st century or the 21st, taking to the streets remains essential to getting one’s point across. An article from History and Policy (History and Policy | Connecting historians, policymakers and the media), a project using academic historical perspectives to enlighten public policy, opened my eyes to how perceptions and responses to rebellion repeat themselves. 19th century French psychologist, Gustav Le Bon, devised a ‘Crowd Theory’ whereby individuals lost rationality and even humanity in a protest group. This thinking runs through both medieval poet John Gower’s depiction of the 1381 rebels as savage wolves and bears and Eric Trump’s characterisation of BLM protestors as feral animals. Similarly, the reaction of the 14th century authorities, denying the scale of unrest by pinpointing troublemaking to “peasants”, misled by radical Lollards under John Wycliffe, is mimicked in the Economist’s description of 1990s poll-tax rioters as “no hopers” living on the peripheries of British society and Boris Johnson’s claim that BLM protests were “subverted by thuggery”. Exploring protest through comparison is not just fascinating. It has the potential to be immensely useful: improving our understanding of and facilitating more open conversations around discontent.