The Cruel Murder of a Young Maiden

Charlotte Young, PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London, investigates Egham during the Early Modern period and in this article, finds out more about a cruel murder.

In the summer of 1613 a murder took place in Egham. Elizabeth Wellome was a maid murdered by her employer, Elizabeth James. The case was significant enough to gain attention from the City of London, and in August of that year an account of the murder was published by John Trundle of Barbican in his pamphlet ‘Three bloodie murders.’ This portion of the text describes what happened:

Let us look with wet eyes, and heavy hearts, upon the cruelty of Elizabeth James, a keepers wife of the Parish of Egham in Surrey, which was thus.

It chanced that a young Mayden, going to seeke a service, came to the house of this woman, and desired her pitty, either to take her in, and entertain her as a servant, or there, as a Boarder to let her live a little time; till she might (thereabout) heare of a service, and she would willingly content her sufficiently, both for her board, and house roome: this woman seeing the Maide, to be a pretty young wench, and handsomely apparelled, but especially minding the profitable promise she made her, with an outward shew of pious compassion, & pitty, took her into her house; where, for a time, she so kindly and lovingly housed her, that the poor harmless Maiden thought her selfe very happy, that it was her chance to find out so good and vertuous a woman. But as tis commonly said; They that know least mischiefe, mistrust least; and so consequently, are soonest deceived. Tis apparent betweene these two, for this deceitfull woman, when shee perceiv’d the Mayd had some store of mony, by little, and little, some at one time, and some at an other, she nere left borrowing of her, till shee had left no more to lend her; and not onely thus deceived her of her money, but her cloathes also: when this poore Mayden had, many times, patiently demanded them, and could not get them, shee was forst to complaine to her Master, who, till then, knew nothing of his wives cozenage, and hard usage of her: he pittying the Maydens plaint, and very (honestly) willing that shee should have her owne, spoke some what sharpely to his wife about them, and forced her to returne unto her, that mony and apparell, that she so deceitfully had taken from her. Whereupon, much strife arose betweene this wicked woman, and her honest well-meaning husband: but of this good that he intended, much more evill succeeded; for the next day her husband beeing gone forth, about his ordinary businesses, as looking to his grounds, and such like: this cruell woman, being empty of all grace (as wee have before sayd) no thought of death and judgement, no love to heaven, nor feare of hell in her bosoms, most mercilesly dragg’d this silly mayden, by the haire of her head, into an inner Roome, where having her at that advantage she looked for, shee drew her knife, and told her that now shee would be soundly revenged upon her for the hard words, and blowes, that she had received from her husband, upon the complaint that she had made against her.

The poore Mayden, seeing there was no hope of life, but in mercy, upon her knees, with her hands hean’d up, her eyes dropping, and such pittifull groaning, as would have extorted pitty from a Pagan, entreated that she would not kill her, and told her, that all she had (if she would be so mercifull) should bee hers, and that she would presently bee gone, without speaking any word to any creature, of the mischiefe, she intended against her.

But neither her promises, prayers, feares, groanes, nor any other pitty-moning action, that past from her, could turne that more then Tiger-hearted woman, from that bloody purpose: for presently she began her butcherie at the throate of this poore Mayden, which when she had so cruelly cut, (her hands reaking in the blood of it) with a hatchet that she had ready for the purpose, shee cut off her head: then by the divell prompted still, to the very utmost of this most horrid impiety, she cut her poore wounded body into many small peeces, some of which she burnt, some boild, and some in the dead of night, she buried in her garden.

Her husband at his returne, when he mist the maiden, thought nothing, btu that his wife had given her her due (as he commanded) and turn’d her away. A day or two after, he was purposed to go digge that bed in his garden, under which his wife had buried the bloody pieces of that poore maidens body: but she perceiving his purpose, desired him of all love, that he would not stirre that bed, nor in any sort meddle with it, because she had bestowed great labor and cost in seedes, that she had but newly sowen in it: he thinking of no such mischiefe, as she fear’d would be discovered, did not goe as he purposed, but forbore it, as she requested.

Thus, for a time, this bloody murther lay concealed, though to reveale it a poore dumb woman, that saw the cruelty acted, many times, and to many persons, by her figures, and dumb shewes, so well as she could did labour her best to betray it. But from al her figures, as pulling her selfe by the haire, drawing her hand over her throate, stabbing her selfe (as it were) upon the breast, wringing her hands, [weeping?] on any thing that she could doe, they could not gather any thing, that they knew how to make any matter of.

But here see the certainty of the sacred word of the Almighty; which says, that he that smites a man that he die, shall die for it, Exod. 21. See here (I say) the goodnesse of this omnipotent God, that sees sinne, hates sinne, and wil punish sinne. When this dumb woman sufficiently expressed her meaning, to make them understand her, a hungry dogge serching about for prey, in the garden of this bloody murdresse, sented out the peices of that poore Maiden, that she had there buried, and then never left scraping up the earth, til he found the head of her, which (by the haire of it) he carried in his teeth, and there before the honest keeper, Goodman James, the bloody harted woman his wife, and other of his neighbors that were with him laid it down: upon the sight of this, they were all very much amazed, the innocent persons at the strangenesse of it, and the murdresse with her feare. Then againe, this poore dumb woman, made figures to resolve them absolutely of the murder, in which she tooke up the head, and pointing to the murdresse, shew’d how she cut it off. Then wafting them with her hand to have them follow her, she went in to the garden, and there pointed to the bed, that the poore murdered maide was hid-in. Her husband seeing this, presently call’d to mind, his wives forbidding him to dig in it, and the excuse that she made to prevent him, and by [illegible passage] began to have setled thoughts of the cruelty of his wife, in the murdering of this Maiden, and presently digg’d a little deeper, and found other small pieces of her. The neighbours likewise, by all these and the guilty [illegible] they say in her (which did as it were [illegible passage] confession betray her) did presently apprehend her as a Murdress, when being carried before a Justice, she was sent up to the White Lyon in Southwarke, where long she lay not ere at St Margets Hill, she was arraign’d and sentenced to her deserved death: but because shee is with child, her execution is put off, till after her delivery/ From this sinne, and all other, good Lord deliver us.

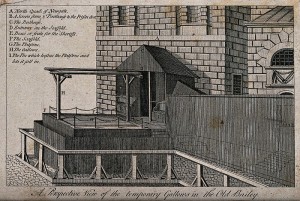

This account is truly sensational. However, examining the trial records for Elizabeth James reveals that John Trundle applied an extreme amount of creative license to his account. Elizabeth was put on trial for the murder of Elizabeth Wellome in June 1613 at Southwark Assizes, but rather than stabbing and dismembering her, the record reveals that she actually just pushed her down the stairs and broke her neck. Crucially, Elizabeth’s husband Thomas James was put on trial alongside her, but he was acquitted. Elizabeth was found guilty, and would most likely have been sentenced to death by hanging. This was the common early modern punishment for those found guilty of murder; indeed, it continued to be used as judicial punishment until the 1960s.

However, Elizabeth managed to get her sentence suspended because she claimed to be pregnant. This was a process known as ‘pleading the belly’, and allowed a woman to delay her sentence until after the baby was born. Elizabeth was remanded in custody, and on 1st July she was examined by a jury of matrons, who concluded that she was lying and was not actually pregnant. In spite of this, she was still in prison the following year; she appears in a list of gaol prisoners presented to Southwark Assizes on 3rd March 1614. Unfortunately this is the last reference to her and it is not clear whether she was eventually executed or not.

However, we do know that she was imprisoned at the White Lion in Southwark. This was an unusual gaol, because it also functioned as an inn for travellers, John Stow’s late-16th century Survey of London describes;

‘ … the White Lyon a Gaole so called, for that the same was a common hosterie for the receit of travellers … This house was first used as a Gaole within these fortie yeares last, since the which time the prisoners were once removed thence to a house in Newtowne, where they remained for a short time, and were returned backe again to the foresaid White Lyon, there to remaine as in the appointed Gaole for the Countie of Surrey.

There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that Elizabeth was guilty of the crime, but John Trundle appears to have gone to extreme lengths in his account to emphasise Thomas James’ innocence. By describing him as an ‘honest well-meaning husband’ who was completely unaware of what his wife had done Trundle appears to have been trying to restore his reputation. The story of how Elizabeth killed her maid would have been well known in Egham, as would the fact that both husband and wife were arrested. Therefore, by publishing an account, albeit not an entirely accurate one, which placed the blame squarely at Elizabeth’s feet, Thomas had some hope of regaining his reputation in the community. However, the evidence suggests that Thomas did not remain in Egham. His name is not present in the lists of tenants entered in the Egham manorial court rolls in 1618 and 1624, and he does not appear in any parish records.

Bibliography

- J S Cockburn (editor), Calendar of Assize Records, Surrey Indictments, James I, (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1982)

- Ida Darlington (editor), Survey of London, Vol 25 (London: London County Council, 1955)

- John Trundle, Three bloodie murders (London: G. E., 1613]