The Grave of the Spanish Tiger

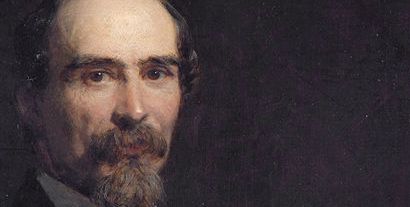

There lies in Virginia Water churchyard an unlikely grave: that of one of the fiercest generals in the Spanish Carlist Wars of the mid-nineteenth century. Ramón Cabrera, who rose from bandit leader to commander-in-chief of the Carlist forces, was known as the ‘Tiger’, an epithet that stemmed less from his military prowess than for acts that would today constitute war crimes.

There lies in Virginia Water churchyard an unlikely grave: that of one of the fiercest generals in the Spanish Carlist Wars of the mid-nineteenth century. Ramón Cabrera, who rose from bandit leader to commander-in-chief of the Carlist forces, was known as the ‘Tiger’, an epithet that stemmed less from his military prowess than for acts that would today constitute war crimes.

The Carlist Wars arose from a dispute over who should inherit the Spanish throne after the death of Ferdinand VII in 1833: his daughter Isabella or Carlos, his brother. This was not just a struggle between adherents of opposing rules of succession but went to the very heart of the principles upon which Spanish society should be built: the Enlightenment versus traditional Catholicism, liberalism (loosely defined) versus absolutism and economic modernisation versus protectionism. Carlos, and with him Cabrera, fought for the latter, the ‘traditional’ vision of Spain.

While Cabrera’s guerrillas scored victory after victory, the acts of cruelty and vindictiveness which accompanied these victories soon earned their leader the name Tiger. As Roy Heman Chant, Cabrera’s English biographer, writes:

The analogy of the tiger emerging from its lair to maim and kill could not be avoided […] prisoners were slaughtered by the dozen, as were civilians who got in the way, or who were nothing more than unhelpful.

Women, particularly the wives and daughters of his opponents, were also targeted. Colonel Alderson of the Royal Engineers, a commissioner sent by Palmerston to observe the situation in Spain, reported back to England of an incident where Cabrera, having billeted himself in the house of a friend and fellow Carlist, made unwelcome advances to his host’s daughter. Upon being rebuffed, he warned her to be ready and willing the next time he came. The frightened daughter told her father of this threat and was at once sent from the town for her own safety. Upon discovering this, Cabrera had the father shot.

Acts such as this, shooting prisoners of war to whom he had promised mercy and showing little regard for the lives or property of civilians made Cabrera infamous. In a brutal act of retaliation, his mother was seized by generals fighting for Isabella and shot by firing squad. This, however, only led to more bloodshed as Cabrera went on to murder over a thousand prisoners and a hundred officers, numerous civilians and even the wives of four of his political enemies.

Eventually, Isabella’s armies succeeded in driving Cabrera from Spain into France, where the French government kept him in a fortress before allowing him to go into exile in England. While he briefly reappeared in Catalonia to fight again in 1848, Cabrera was by now a spent force. He returned to England and married the much younger Marianne Richards, the daughter of a wealthy landowner.

After living in London for the first few years of their marriage the couple moved to Virginia Water and the mansion that now sits at the heart of Wentworth Golf Club. Chant picks up the story:

in London and Wentworth, the magic of his name still strong, Cabrera had frequent visits from Carlist emissaries and conspirators, received the successive Pretenders themselves, and engaged in lengthy correspondence with them […]

But Cabrera’s enthusiasm for militant Carlism […] became less and less as the experience of true Liberalism and the comforts of English country life influenced his own thinking.

The Tiger then settled down to live the life of a prosperous English country gentleman. When he died on 24 May 1877, hundreds of people from Virginia Water, Egham and the surrounding area attended the funeral, knowing Cabrera only as a respected squire and local patriarch. However, the press knew something of his past. The Echo recalled how, upon Cabrera’s arrival in London “men shunned him and fathers forbade daughters to dance with him or even to touch his hand.”

“No one”, it concluded, “was more blackly stained with blood, more depraved by cruelty, or more degraded by treason”.