The Old Bailey trial of Charles Nash, 1864

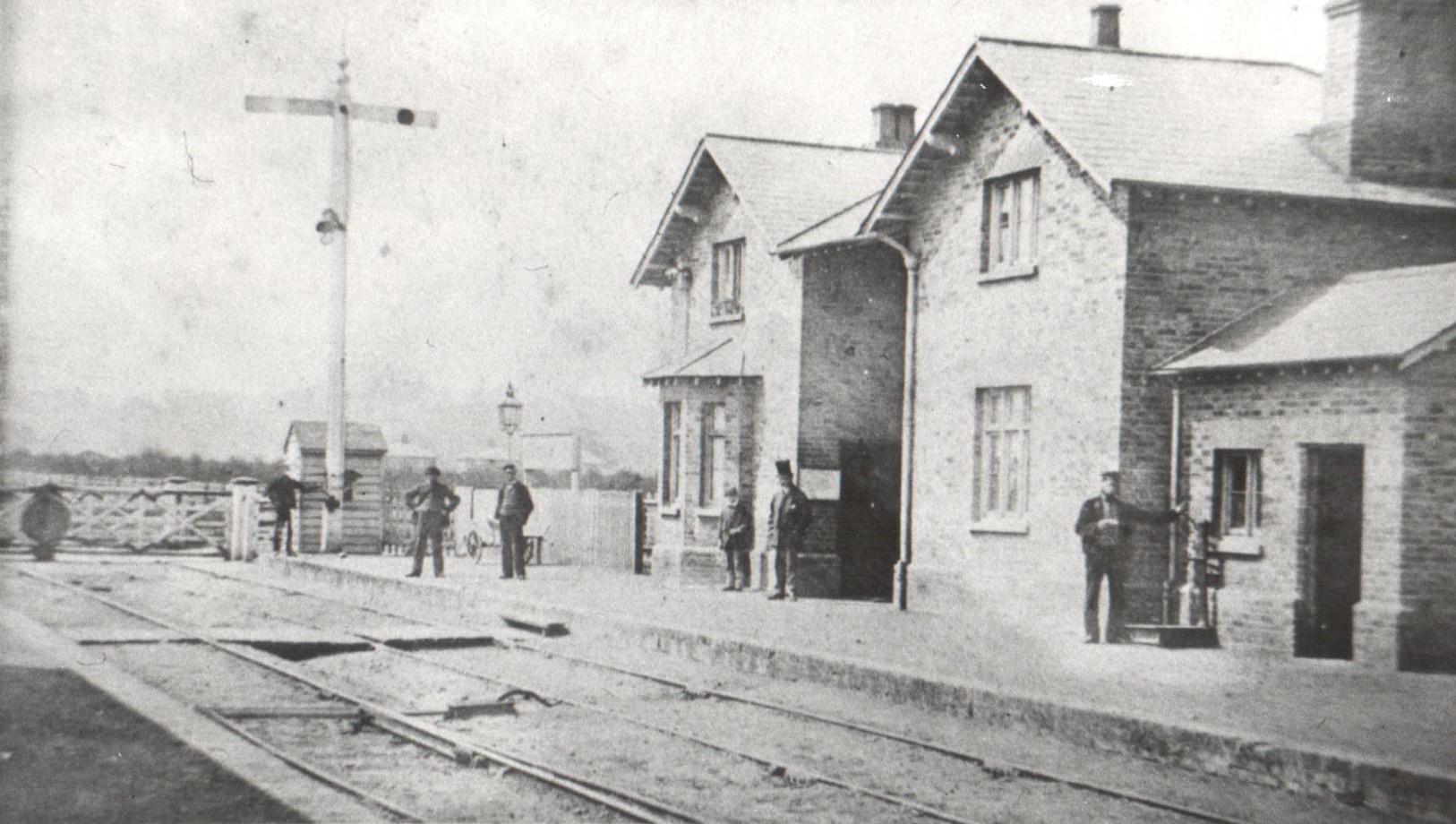

A fatal rail accident which occurred at Egham just before 7.30pm on 7th June 1864 is described in The Railway Comes to Egham, an article published by Egham Museum on 17th April 2018 https://eghammuseum.org/blog/2018/04/17/the-railway-comes-to-egham/.

An interesting sequel to this accident was the Old Bailey trial of Charles Nash on 24th October 1864[i] for unlawfully obtaining by false pretences an order for the payment of £20, with intent to defraud.

He had written to the London and South Western Railway Company:

Dear Sir—I beg to call your most serious attention to an accident I met with in coming from Ascot on Tuesday evening last, 7th June, I was in the third carriage from the guard’s van, and was run into by a train, which was coming at full speed on the same metals; we received an order to have all tickets ready, I noticed the guard of our train jump out, and I jumped out, and fell, and was picked up by a gentleman. I have had Mr. Hunt, my family physician, to see me, but feel no better. I beg to say it is bad management of the company’s servants to allow a train at full speed to run into us.—Signed, Charles Nash.

After Nash was interviewed on 13th June by the secretary of the railway company, his assistant Frederick Julius Macauley and Mr Jenkins, an official, in the presence of his doctor, he was awarded compensation of £20. However, the company later doubted that the claim was genuine and a court heard the evidence summarised below.

| Prosecution |

| MISS ELIZABETH TURNER who lived with her parents, at 7 Tranquila Terrace, Hammersmith where Nash had been residing for nine months, said Nash was in at tea on 7 June from 4.15 to 5 pm. She saw him leave the house with his wife and children between 6.30 and 7 and go straight down Tranquila Terrace. He came home at 20 to 3 next morning and her father got up to let him in. He said, “Thank you, Mr. Turner,” and walked up stairs. At half-past 8, as she was going to work she noticed he was limping. When she asked what was the matter with his feet he said, “A horse has stepped on me, Betsy.” He said nothing then or later that day about the railway accident on the Egham line. |

| JOHN TURNER, her father, testified that on the day of the accident he left home at about 8 am, just after Nash and did not return until about 9 pm and went to bed about 10: “I was disturbed by the prisoner about twenty minutes to 3 o’clock—he knocked twice, and I let him in, and told him he was very late—he said, ‘Yes, I am,’ he first thanked me for letting him in—there did not seem to be anything the matter with him.” Next morning he heard his daughter say to Nash: “You seem lame” and the reply: “Yes, a horse has stepped on my toe”. Shortly afterwards Turner went out, and heard there had been an accident. On Thursday, Nash still said nothing about it. “On Friday morning he said that he had met with an accident, and had written to the railway company, and expected someone to call, —he showed me his leg, and I saw bruises—I said, ‘You told my daughter the other morning that a horse had stepped on your toe.’ He said, ‘Oh, I might have said so, but I did not mean it.’ His wife said, ’That scratch on your eye is more like a woman scratching you than anything else, I do not believe you were in the accident at all’—I do not think he made any answer to that—he left my house about a fortnight afterwards on a Sunday, and I did not see him after that—his wife and family remained behind for some considerable time.”

Sometime previously Turner and Nash had disagreed concerning a scheme where one person signs his name to provide credit for another. Nash accused Turner of stealing and reported him to the police but Turner was discharged as the case was heard in the wrong district. Turner could not remember if this was before or after the accident and claimed “I have never said since to any one that the prisoner should rue the day when he gave me in custody—I know a person named Lyons, and I have seen him lately—I never told him that I would fix the prisoner for looking me up—Lyons did ask me whether the prisoner really was at the races or not—I replied that I did not know, as I had not seen him that day—I did not also say that I had got the prisoner right now, and I owed him a spite as well as Seymour—I never thought of such a thing—I did not say that I would give him as much as I possibly could, or that it was the worst day’s work I ever did in locking the prisoner up, for I really believed he was at Ascot.” |

| MRS ELIZABETH TURNER, the wife of the last witness, confirmed that the prisoner lodged in their house. She had been at home all day on the 7th. Nash had come in to tea between 5 and 6, and went out again at nearly 7 pm. Both she and Nash read the newspaper which reported the accident but he did not mention the incident. She saw the prisoner’s leg “it was a little bruised, and it turned green and black on the shin-bone—I did not notice anything on his face.” |

| THOMAS SEYMOUR, landlord of the Greyhound public-house Fulham, said he had known the prisoner since October 1862 when they had both worked for Dr Winslow. On the day of the accident at Egham, he left his house at quarter past 6 to go to Hammersmith; on returning at about quarter to 7 he saw Nash going towards the river. Seymour met a man named Gibbs, who remarked “There is your friend” and he replied “It is a good job I am not near him, or else I should give him a shaking.” He heard of the accident the next evening. Some days afterwards, he heard that Nash had said that he was at the accident, “but I thought he would not make a claim on the company.”

Seymour went on to insist that Nash and he had no quarrel at Dr. Winslow’s. “I never got spirits for patients, or porter; it was strictly prohibited—the prisoner wrote to the Commissioners of Police [0n 3 June] stating that I kept a disorderly house, thieves, and prostitutes, and all sorts of things, and I said that it was a good thing he was not a man with money, or I should spend £100 over him—it was not true—I never said that I would get him out of Hammersmith—I should have brought an action—I should have wanted money out of him, but not his removal… I never had any complaint—it is quite untrue.” |

| THOMAS GIBBS, a stableman, recollected seeing the prisoner – who he had known for several years – on the day of the accident, and saying to Mr. Seymour,” There is your friend.” He heard on the Thursday that Nash was going to claim compensation, “which astonished my mind.” |

| GEORGE WALE testified that he lived at 23, Tranquila Terrace, Hammersmith, and was formerly beadle of the parish and summoning officer until he was discharged for getting intoxicated.

He heard of the accident at Egham on the next day, Wednesday, 8th June. He recollected seeing Nash the day before—“he passed by my window about a quarter before 7 in the evening, coming in the direction from his house and going towards Queen-street, and somebody drew my attention to him at a quarter to 7 as near as can be—I afterwards heard of his claim against the company.” |

| His wife ELIZA WALE also saw the prisoner, who she knew well by sight, at a quarter or twenty to 7 when she was working in her parlour with a view of the road. She heard of the accident next day, and “it may be a week afterwards I heard he would soon have a good thing from the railway—a man who was speaking about it told me that—I never mentioned it to my husband.” |

| THOMAS COTON, a labourer of Fulham said he had known the prisoner about eighteen months. On 7th June he saw the prisoner at the end of Chancellor Street, Hammersmith, from half-past 7 to 8 pm. “He asked me if I knew where George Mercer was, and I said that I did not know, neither did I care—I am sure it was 7th June, because it was on my birthday.” |

| GEORGE FLETCHER, warrant-officer at Hammersmith Police-1, took nearly two months to find Nash after the warrant was issued “I found him on 7th August, living at Plymouth, in the name of Wheeler… he was told that I took him for obtaining a coat of Mr. Swainson—on the way to the station, he said, ‘Have you anything against me?’—I said, ‘Yes, I have a warrant against you for obtaining some money from the South Western Railway’—he said, ‘That is wrong,’ and went to the station.” |

| Defence |

| ALFRED HUNT, surgeon, testified that Charles Nash had painful bruising on each leg and cuts on his face which made it impossible for him to work at his usual business. |

| EDWARD GURTIN, a jeweller, said that he took the Royal Hunt Cup to Ascot, travelling in the same carriage as Nash and a lady (later identified as Priscilla Watkins) on Tuesday 6th June [sic] and they exchanged pleasantries. In the evening he recognised him on the train and got into the same carriage. After the crash he saw him bleeding from his forehead and heard him complain of his shins being cut although he did not see this happening. The lady showed no signs of bleeding or bruising. Nash was not stunned and did not need picking up. Gurtin gave Nash his address and another gentleman, Mr. Graham, of Onslow Terrace, gave him his card.

Gurtin travelled into London with Nash and the lady, and went for a drink with them between 10 and 11pm at Waterloo. Nash escorted the lady into a Hansom cab then, still complaining of his shins being hurt, walked slowly with Gurtin over Waterloo Bridge to a coffee-shop for a cup of tea, and a slice of bread and butter. They took a Hansom cab to the Knightsbridge cabstand, where Gurtin got out, but Nash ordered the cabman to drive him to the Broadway, Hammersmith. At first Gurtin suggested that the lady’s name was Jenkins but corrected this to Watkins when her name was called out in court. He said he had seen her at Hammersmith police court when she was giving evidence there (presumably a pre-trial hearing) but that he had not known either her or Nash before the accident. “It was quite an accident my going in the same carriage, and my getting into the same carriage coming up was very odd—Nash made a remark about it—he said, ‘It is very strange that this gentleman should go up and down in the same carriage’—he said that to all who were in the carriage, I presume—perhaps it was to me, or it might be to the lady who was with him; I do not know.” |

| PRISCILLA WATKINS said that she had gone to the races with Nash on 7th June and spent the day with him. They travelled both ways in the same carriage as Mr Gurtin. At Ascot she and Nash spoke to a friend named Bacchus and they had a drink together.

Initially she said that she was married but then admitted that this was a lie. She had been living with Nash some three or four weeks before the accident and passing herself off as Mrs Nash, unaware that he had a wife, but she did not do so at Ascot. She said that Nash “had his eye cut, and his legs were very much hurt” in the crash and that he was given brandy by a gentleman from a nearby cottage, but that no-one had needed to pick him up. She confirmed that she went to a pub at Waterloo with Nash and Gurtin before taking a Hansom cab home. She added that she was injured, and obtained £20 compensation from the company. |

| GEORGE HENRY BACCHUS, a clerk testified that he was Ascot on the day of the accident. He saw Nash who he knew slightly from shooting matches and commented that he was with a female in hat and feather, although he did not admit that he already knew her. They all went for refreshments together at 3pm. |

| JOHN SERJEANT from Bracknell was at Ascot races on the Tuesday. He knew the prisoner well and he saw him there about 1 o’clock, just before the first race commenced, accompanied by a young woman. They spoke for a few minutes. |

| JAMES LYONS of Hammersmith, said that he knew the witness John Turner, and heard him say after Nash had been charged with this offence—”Well, I believe myself the man was at Ascot,” and that it was the worst day’s work that Nash ever did to put him in prison on that bill. Lyons replied, “It is my belief that Wale is wrong in saying that he saw him on that day,” and then Turner laughed. |

Somebody seems to be lying but who? And why? Was Charles Nash innocent or guilty of trying to defraud the train company? Find out the verdict here!

Margaret C Stewart

[i] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (1864) Charles Nash. Deception: Fraud

https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?name=18641024 [Accessed 21 March 2018]