The Plague Comes To Egham

Plague was a common occurrence in Early Modern England. Across the country, thousands of people died and communities were devastated. The widely accepted cause of plague was the miasma theory; that the disease was spread by infected air. Indeed, a pamphlet dedicated to the casualties of the disease published by Henry Chettle in October 1603 opens with the statement,

‘It is no doubt that the corruption of the ayre, together with the uncleanly and unwholesome keeping of dwelling, where many are pestered together, as also the not observing to have fiers private & publiquely made as well within houses, as without in the streets, at times when the ayre is infected, are great occasions to increase corrupt and pestilent diseases.’

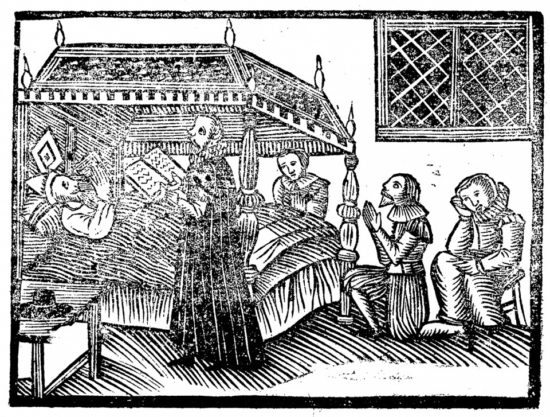

The 1603 outbreak is believed to have been bubonic plague, the symptoms of which included chills, fevers, muscle cramps, seizures, swelling of the lymph glands, gangrene, vomiting blood and extreme pain. Life expectancy for an adult after the disease was contracted was a fortnight at most, but much less for children and the elderly.

Egham’s Plague 1603-4

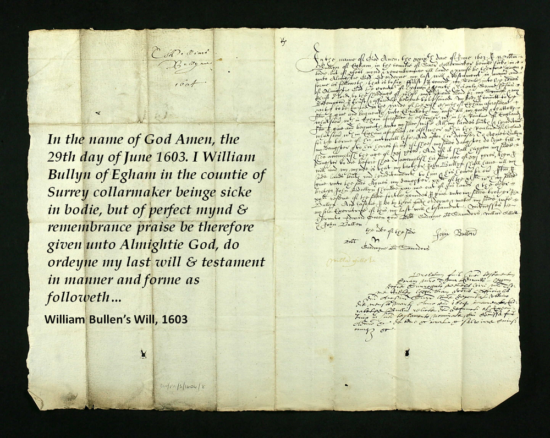

William Bullen was a collar maker living in Egham. He was married to Elizabeth, and they had at least 5 children; John in 1586, Ann in 1589, Mercy in 1592, Katherine in 1598, and William in 1601. William’s occupation would have kept him constantly busy. A staple of any Tudor outfit, male or female, was a prominent collar, more commonly known as a ruff. These were created by gathering and folding several yards of fabric into a circle, heavily starched to keep its shape. They were detachable and could be coloured blue, yellow, pink or mauve using vegetable dies. As England moved into the 17th century fashions changed, and the ruff was replaced with a wing collar. These were stiff, starched single pieces of fabric, much more conservative in appearance.

However, before William could adapt his pattern book a calamitous event swept the nation, and devastated his family; the plague of 1603. Plague was a recurring problem; there had been outbreaks in Tudor London in 1498, 1535, 1543, 1563 and 1589. It was a dreaded disease, for which there was no cure, and an estimated 30,000 people died in England due to the 1603 outbreak.

It is possible that William Bullen’s occupation had caused him to travel into an infected area, perhaps to London, where he had caught the disease. He returned to Egham, and it spread to his children and neighbours. When his children were dying he was definitely also ill, because the day before John’s funeral he hastily wrote his will. It is not known exactly when William Bullen died, but he was buried at St John’s, Egham on 6th July 1603, only a week after he wrote his will.

Parish registers did not often record a person’s cause of death, but an exception was made in the case of plague. The first death by plague recorded in the parish registers of St John’s, Egham was that of Mercy Bullen, who was buried on 18th June 1603 aged only 11. Within days her brother John had also died, and was buried on 30th June.

At the beginning of the 1603 outbreak Egham hosted a distinguished visitor. The Venetian Secretary in England, Giovanni Carlo Scaramelli, passed through the ‘village, which is two short miles from Windsor’, on his way to an audience with the King. The Royal court had withdrawn from London to Windsor at the first sign of pestilence so the lives of the monarch and his family would not be risked. Scaramelli’s visit was not a long one; he wrote to the Doge and Senate from Egham on 23rd July, but by 30th July he had relocated west to Sunbury. No doubt news reached him at his lodgings that the three Bullens had died of the plague, and that the Goodwyn household was also infected; Thomas and Henry Goodwyn were buried on 25th and 29th July respectively. The Royal Court also felt that Windsor was not far enough away from infection, and had relocated to Hampton Court Palace by the end of the month.

A total of 68 deaths were recorded as caused by plague in the parish register of St John’s, Egham; 39 of these were children. Even though this was a very small portion of the estimated 30,000 across England, it would have caused extreme disruption and sorrow in the community.

Egham’s Plague 1606

In 1606 another outbreak of plague hit Egham, although it was not as devastating as the plague of 1603 and only 4 people died. The first recorded deaths in the parish register were of Henry Anselm and his wife Ann, who were buried in the same grave on 28th September. The only other resident of Egham who succumbed was Katherine Parker, who was buried on 30th October.

The final victim was a young woman named Bridget. The parish register records that she had been ‘travelling from Stanwell and so through Egham’. She died here at the beginning of October and was buried at St John’s on the 11th. It seems likely that she had been staying at one of the inns, perhaps the Catherine Wheel or the Red Lion.

This is an example of the dangers Egham faced being a coaching town, and raises many questions about what caused this mini outbreak. Was plague already in Egham when Bridget arrived? Had Stanwell become infected, and was Bridget trying to escape to safety? Did the Anselms and Katherine Parker catch the plague from her? It seems likely that she was already ill when she arrived in Egham, because Stanwell is not far away. She must have become too ill to continue her journey.

Egham’s Plague 1608

The final outbreak of plague in early 17th century Egham occurred in 1608. Once again, it was caused by a traveller passing through the town. A woman described simply as ‘a

young wench’ died on Egham Hill, and was buried there on 3rd August.

The disease quickly spread through several households in the town, leading to the deaths of Elizabeth May and her daughter Alice; Joan and Leonard New, the children of Leonard and Elizabeth New; and Ann Coleman, a widow. Was this as a result of the ‘wench’ passing through? Who was she and where did she come from?

One other victim was a young man called Thomas Field. His father lived in Windsor, and Thomas worked as a servant to a gentleman named Patrick Derick, who owned a house in Egham.

London had also been hit by an outbreak of plague in 1608, and wealthier families tried to escape the disease by leaving the city and seeking refuge in their country homes. Perhaps Patrick Derick had removed his household to Egham hoping it would be a safer location?

Was there plague in Egham in 1665?

St John’s Church parish records from 1665 do not list the plague as cause of death in Egham, as they had done in prior years. Does that indicate there were no plague related deaths since the 1608 outbreak?

Logically, the plague must have reached Egham in 1665, even if it is not visible in the parish registers. Daniel Defoe’s ‘Journal of the Plague Year’ does not mention Egham, but Defoe states that he had heard accounts of numerous deaths in Staines, Chertsey and Windsor. It is highly unlikely that those towns would be infected and Egham be clear. After all, as with the 1606 and 1608 outbreaks, all you need is one traveller passing through!

And yet, more or less, maugre all the caution, there was not a town of any note within ten (or, I believe, twenty) miles of the city but what was more or less infected and had some died among them. I have heard the accounts of several, such as they were reckoned up, as follows:-

In Enfield 32 In Uxbridge 117

“ Hornsey 58 “ Hertford 90

“Newington 17 “Ware 160

“ Tottenham 42 “ Hodsdon 30

“ Edmonton 19 “ Waltham Abbey 23

“ Barnet and Hadley 19 “ Epping 26

“ St Albans 121 “ Deptford 623

“ Watford 45 “ Greenwich 231

“ Eltham and Lusum 85 “ Kingston 82

“ Croydon 61 “ Stanes 82

“ Brentwood 70 “ Chertsey 18

“ Rumford 109 “ Windsor 103

“ Barking Abbot 200

“ Brentford 432 Cum aliis.

What do you think? Read more about London’s Great Plague of 1665 in Guildhall Library’s The Great Plague, 1665 online exhibition.