The Totem Pole at Virginia Water

The Totem pole has provided an eye-catching site for visitors to Virginia Water for over sixty years. It was formally installed in June 1958 and stands within the Valley Gardens area of Virginia Water, which forms part of the wider Windsor Great Park .It was given as a gift to Queen Elizabeth II from the people of Canada to mark the centenary of the proclamation of British Columbia as a crown colony, which had been founded in November 1858. The totem pole stands at one hundred feet tall, with one foot equalling a year since the proclamation.

Totem Poles

Totem poles are now found throughout the world but originate from The Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and Alaska. They are traditionally carved from a single red cedar tree and can depict either mystical or historical narratives, and often also depict animals native to the Pacific Northwest as well as human figures. These figures all carry symbolic meaning. Bright colours are often, but not always, used to decorate the pole after it has been carved. The totem pole at Virginia Water is an example of a ‘memorial pole’, as it commemorates a historic event. They are also seen as symbols of power and strength for many First Nations people.

In the mid to late nineteenth century there was a surge in interest in the art of the Northwest Coast of North America. This was coupled with widespread setter colonisation and an increase in tourism to the pacific northwest area of Canada, mainly as a result of railway expansion. Europeans saw the art of the First Nations, particularly totem poles, as exotic and would often purchase miniature carved poles as a souvenir of their travels. Many of these items were not carved by First Nations people, but by European settlers wishing to make a profit from travellers. Many historic artefacts were also forcibly taken from First Nation land and shipped to various museums across Europe.

The totem pole that stands at Virginia Water was carved by Chief Mungo Martin, a renowned First Nations artist and a member of the Kwakiutl tribe. Martin was one of the last surviving master carvers in Canada at the time and helped to recreate a number of totem poles for museums in British Columbia, in order to preserve his communities’ traditions for the future. There were only a few master artisans who could carve totem poles according to the traditions of their communities at this time, and sadly this situation has not changed. Martin also created an identical pole to the one that stands at Virginia Water, which was raised outside the National Maritime Museum in Vancouver to also commemorate the centenary.

Canadian Links in the Local Area

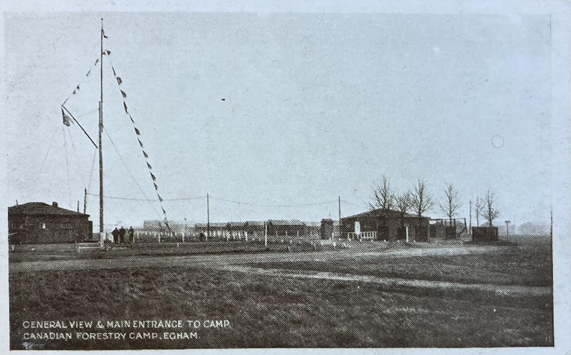

During the First World War Canada was still a part of the British Empire, meaning that they joined they war effort when Britain declared war in 1914. Timber was a valuable resource which would be crucial to the war effort but required highly skilled men to fell the trees. In 1916 Britain requested aid in felling trees needed for the war effort. The colonial secretary wrote to the General governor of Canada. In response, the Canadian Forestry Corps were mobilised and were granted the task of chopping down timber in Windsor Great Park.

‘H.M. Government would be grateful if the Canadian Government would assist in the production of timber for war purposes…H.M. Government would suggest that a Battalion of Lumbermen might be formed of specially enlisted men to undertake exploitation of forests of this country’-Colonial Secretary to the General-Governor of Canada, written February 1916

Of special note is John Jakomoulin (or Chookomolin), who served with the Canadian Forestry Corps. He was a member of the Cree Nation, part of the First Nations of Canada. He died on 20th September 1917 at the Windlesham Military Hospital at the age of twenty two. John Jakomolin is among thirty-two Canadians who are buried in St Jude’s Churchyard, Englefield Green, who all died as a result of their service during the First World War.

A new war memorial acknowledging the sacrifice of those in both the First and Second World War was unveiled in 2016 to coincide with the centenary events of 2014-18.

The Future of the Totem Pole?

In the summer of 2021, the Totem Pole and surrounding area was closed to the public, while renovation works were carried out in order to conserve the totem pole for future generations. It had previously been repainted in 1985, but no mention was made of the involvement of First Nation peoples during the 1985 renovation, despite the totem pole being highly important to certain communities.

Many totem poles were removed without consultation from First Nation lands in the late nineteenth century and continued until the early-twentieth century, partly as a response to legislation banning indigenous culture passed by the Canadian government. In Canada, the ‘Indian’ Act of 1867 and its subsequent amendments in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century effectively banned parts of First Nation culture. Many communities were restricted in observing their cultural traditions until the revision of the ‘Indian’ Act in 1951, less than a decade before the pole was placed in Windsor Great Park. This included the carving of totem poles. Before 1951 it was not uncommon for individuals to be arrested by police if they attended ceremonies related to their heritage, highlighting the persecution these communities faced.

Katie Smith

For more on the Canadian Foresters in Egham, follow the link below!

<a href=”http://<http://eghammuseum.org/canadian-forestry-corps/>

Further Reading

‘100ft. Totem Pole For Queen’, News Chronicle, 19th June 1958, British Newspaper Archive,< https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003215/19580619/009/0001> [accessed 7th October 2021].

‘Canadian Foresters in Egham’, Egham Museum, <http://eghammuseum.org/canadian-forestry-corps/> [accessed 30th September 2021].

‘Going to War’, Canadian War Museum, <https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/>[accessed 7th October 2021].

‘Masters of the Pacific Coast: The Tribes of the American Northwest – Survival’, Box of Broadcasts, 20th May 2020, BBC4,< https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/search.php/prog?q%5B0%5D%5Bv%5D=Masters+of+the+Pacific+&search_type=1&is_available=&q%5B0%5D%5Bindex%5D=&source=&date_type=0&date=1952-01-01-00-00&date_start%5B1%5D=01&date_start%5B2%5D=01&date_start%5B0%5D=1952&date_start%5B3%5D=00&date_start%5B4%5D=00&date_end%5B1%5D=11&date_end%5B2%5D=06&date_end%5B0%5D=2021&date_end%5B3%5D=23&date_end%5B4%5D=59&institution=&sort=relevance >[accessed 23rd October 2021]

‘Private John Chookomolin’, Commonwealth War Graves Commission,< https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/401109/JOHN%20CHOOKOMOLIN/> [accessed 30th September 2021].

‘Recruitment’, Ontario Archives,< http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/posters/recruitment.aspx> [accessed 7th October 2021].

‘The Totem Pole Restoration’, Visitor Updates-Windsor Great Park, < https://www.windsorgreatpark.co.uk/en/visit/visitor-updates> [accessed 7th October 2021].

‘TOTEM POLE ARRIVES’, British Movietone on YouTube,< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kKiGjVi5vHc>[accessed 19th September 2021].

‘VICTORIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA’, Illustrated London News, 21st June 1958,< https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001578/19580621/043/0018> [accessed 7th October 2021].

‘WE REMEMBER JOHN JAKOMOLIN OR CHOOKOMOLIN’, Imperial War Museum,<https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/5958805> [accessed 21st September 2021].

Fielder, Andrew, Windsor Great Park: A Visitor’s Guide(Copper horse Publishing; Windsor, 2010).