Thomas Holloway’s Two Legacies

by Anna Kutuzova

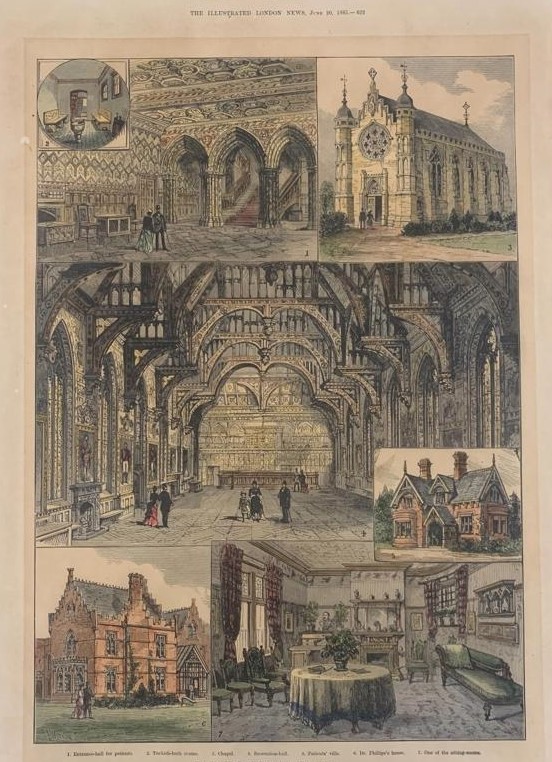

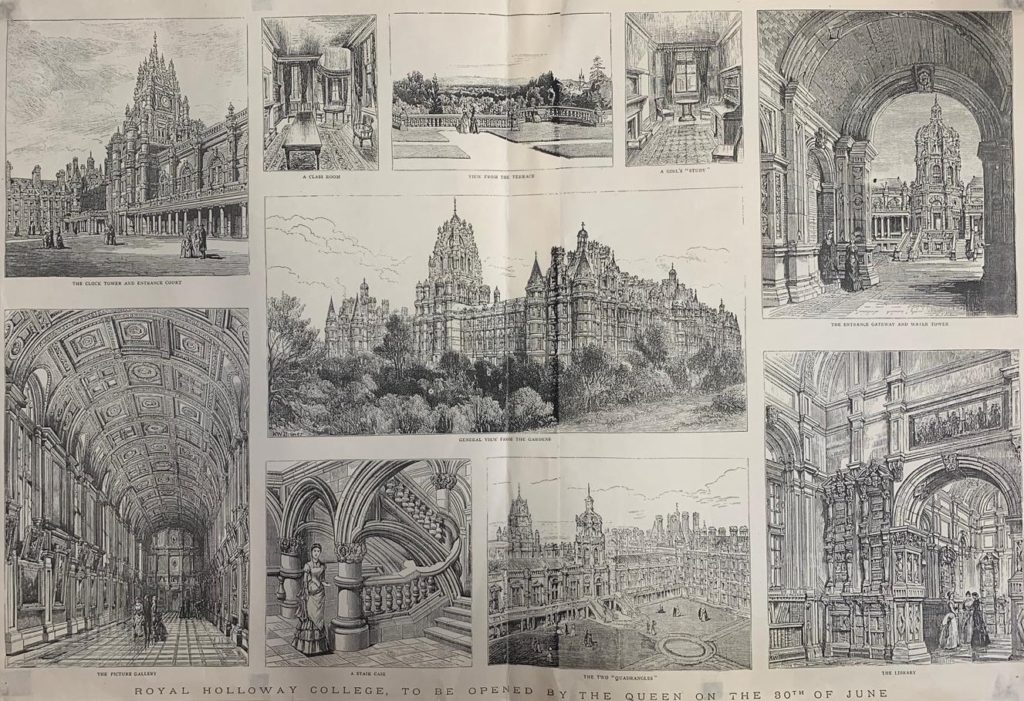

The opening of both institutions, but especially the university for women, attracted a lot of attention bringing much fame not only to the people involved into the projects, but also to the sites making them appealing points of destination for all sorts of people, including painters, photographer and journalists who did not spare their talents to praise the exquisiteness and sophistication of the architectural masterpieces.

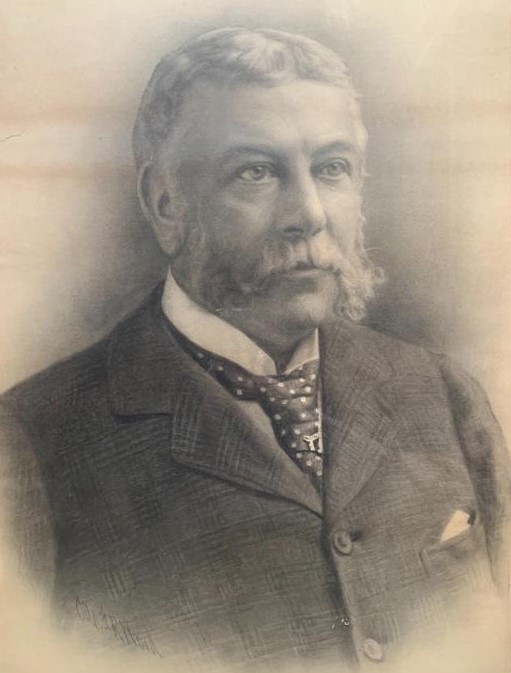

Thomas Holloway

“In his life and achievements Thomas Holloway […] epitomized the finest qualities of his age – an age of which it may be fairly said he was as much an architect as a product.”

‘Who can deny that he is one of the wonders of the nineteenth century?’ Those words were written about Thomas Holloway by an admiring journalist in 1877 when the public attention was captured by Holloway’s intentions to open a sanatorium and a women’s college.

Who was Thomas Holloway at that time? By 1877, the founder of both institutions, Thomas Holloway, had become a famous manufacturer of two patient medicines: Holloway’s Ointment and Holloway’s Pills. Holloway’s talent was in advertising his products which appeared even on the hoardings near the Niagara Falls and at the foot of the Great Pyramids. He was ‘a man who spent every moment of his adult waking life preoccupied with money’ and ‘his understanding of marketing techniques was decades ahead of other businesses’.

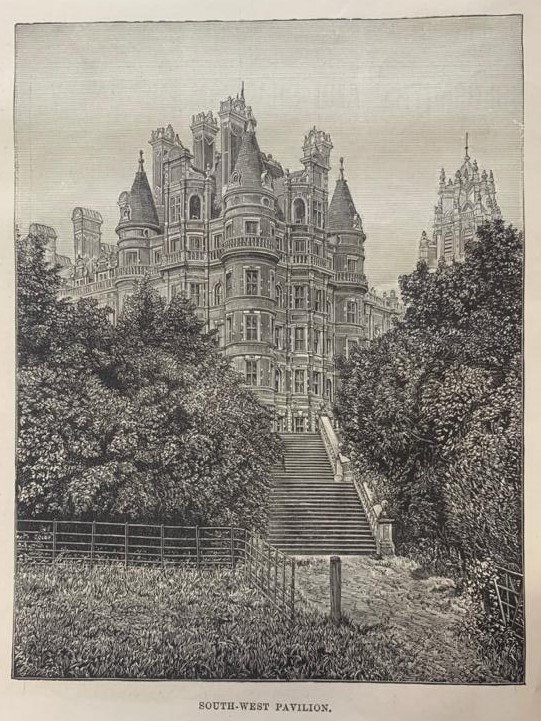

Having made a large fortune from the sale of his products and provided for his family members, Thomas Holloway decided to spend his fortune on a philanthropic purpose as he had no children to whom he could bequeath his money. In 1861 he attended a meeting in the Freemasons’ Hall where the philanthropist Lord Shaftesbury made a speech on the increasing numbers of middle-class people with mental illnesses. This marked a turning point of his life as he was affirmed in his idea to found an asylum. Holloway recognized the need for an asylum for the middle classes who lacked mental health provision in comparison with upper-classes that had a capacity to take care of their own and the lowest classes for which already existed a number of asylums. Holloway sought to fill this gap and, therefore, he took this project very seriously. He visited several asylums which he found depressing and failing to contribute to the recovery. He, therefore, decided that his institution should be ‘spacious, comfortable and welcoming’ and ‘an inspiration which would be copied by others’. In February 1871, Holloway met with the Commissioners in Lunacy, who approved of his plans. He then allocated £300,000 for the construction of the asylum and then the Trust Deed was executed. Previously to that, Holloway had bought Trotsworth Farm at St. Ann’s Heath, Virginia Water, in Surrey. As a talented advertiser, Holloway had chosen Trotsworth Farm primarily because of its elevated position. ‘It would be clearly visible to the travelling public from the railway running close by and thereby become its own advertisement.’ In terms of architectural style, Holloway initially favoured Italian style, but by October 1871, he had turned his attention to the ‘Flemish’ style, like the Cloth Hall in Ypres, one of the best-known secular Gothic buildings in Europe. Holloway put in a lot of effort himself in designing the plans for the asylum, but he also had various advisors on the matter of practical and architectural knowledge.

William H. Crossland: The Project that Changed his Life

The next step was to launch the competition through which the best design for the asylum was intended to be achieved. By that time William H. Crossland had had an impressive portfolio that included Rochdale Town Hall (built 1866–71), which ensured that he was included into the list of pre-selected architects who were to be invited to the take part in the competition. Crossland had a good start in life and trained under the supervision of George Gilbert Scott, a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, which gave him a certain status. There are only a few images remaining of Crossland and almost nothing is known of his personality, although he was described as a ‘fine quiet man with a dream like dignity in him.’ He sought out the opportunities and found the project of the sanatorium extremely appealing, despite realizing that it was potentially too large for one architect. He, therefore, persuaded Edward Salomons and fellow London architect John Philpot Jones, who was responsible for most of the work on the design of the asylum, to become his partners for the competition. This was the only time in his career when Crossland worked with other architects. The entries to the competition were anonymous and, as usually practised, they were identified by an unrelated ‘motto’. Crosland and his colleagues used the motto ‘Alpha’, which was placed first by Holloway and his advisors when they gathered to judge the entries. The competition took place in the spring of 1872 and was announced in the The Builder at the end of June 1872. When the results of the competition were announced Crosland was taking a holiday in Nova Scotia, Canada. He received the result through telegram and later recalled: ‘When the adjudication was given in our favour I was up in the woods of Nova Scotia, thinking a good deal more of salmon and moose than of Sanatoria.’ However, it was the success in this competition that completely changed the direction of Crossland’s professional and private life.

Thomas Holloway Supervised Every Detail

There ended up being two plans, the one that won the competition and the other that was developed out of further work but neither of these plans gave the layout that was actually executed. The work on the asylum began in 1873 and in May of the same year the first brick was laid by Jane Holloway and the second by Thomas Holloway. Even after Crossland and his partners had won the competition, Holloway continued to contribute significantly to the construction of the asylum. When in the middle of the work, John Philpot Jones, responsible for the design of the Sanatorium, died unexpectedly Crossland was left with the entire responsibility for the supervision and quickly learned that Holloway was a meticulous client who visited the building site daily and checked even small details. Crossland recalled at the 1887 R.I.B.A. meeting that ‘Mr Holloway, who possessed amongst his other many good traits, one of looking into everything which was going on, and especially into those things which had the appearance of being hidden away […]’. Holloway was particularly insistent that the Sanatorium should be non-denominational as he distrusted formalised religion. He stated that there should be no chapel but eventually bowed to the Commissioners of Lunacy as a chapel was a legal requirement for such an institution. The chapel was designed by Crossland during 1881 when he was already supervising the College. The chapel was constructed as a separate building and the work on the main building continued. By that time the interior of the Sanatorium was well advanced. There appeared a comment in The Builder saying that the Sanatorium would open soon and that ‘such a combination of rich colouring and gilding is not to be found in any modern building in this country, except in the House of Lords.’

(PR323)

The Idea of the College

Not long after the work on the asylum began, Holloway started planning his second project which initially was conceived as a convalescent home for incurables. However, the purpose of the second institutions was changed, most certainly at the suggestion of Holloway’s wife Jane, was changed to a college for the higher education of women. The education of women ‘was one of the great Liberal causes of the age and, in so far as anything is known about Holloway’s politics, it is clear that he allied himself with the radical Liberalism common among his fellow businessman.’

Although having been advised to hold a competition for the design of the college, Holloway informally addressed Crossland, seeking his advice on the style of the future college. After they had agreed on the impending obsolescence of the Gothic style and a return to the Renaissance of the 16th century, Holloway asked Crossland what he would do if he became a competitor. Crossland replied that he would visit Touraine in order to sketch the Renaissance châteaux that he and Holloway had discussed. Holloway then asked: ‘Will you do this Mr Crossland?’ Having received a positive response Holloway patted Crossland on the shoulder saying, ‘My boy, you shall have the work’. This conversation secured the largest and most important work of his career.

Crossland set off for Touraine in order to measure and sketch some of the chateaux in the valley of the Lorie, and in Fontainebleau, and especially Château de Chambord, which was an essential inspiration was for the college. During their trip to France, Crossland and Holloway visited different chateaux but it was Chambord indeed that impressed them the most. Crossland recalled that they decided there in the valley of the Loire that their building should be similar to Chambord but with red brick which was available in Surrey. After the trip to France, Crossland spent two years working on the plans, elevations and fine details. Although the motifs from all the chateaux visited in the Loire were used in designing, the chateau of Chambord was a particular source of inspiration. Crossland drew substantially on the ground floor plan of the chateau and more generally on the overall style. Although Royal Holloway College and Chambord have some similarities, such as the engaged or coupled turrets, the elongated chimneystacks, dormers and balustrades, the buildings are strikingly different in size, in composition, in detail, and in colour (the cool grey of Chambord was changed to red (Reading bricks) and white (Portland stone)).

In 1874, Holloway purchased the ninety-four acre Mount Lee Estate. The site was chosen based on the Holloway’s intention to make the College its own advertisement – clearly visible from distance and from the railway line from London.

After many months of work on designing the college, Crossland and Holloway were told that the architectural style of the College was inappropriate and less suitable than the prevailing style of Cambridge and Oxford. For Holloway the appearance of his Ladies’ University was crucial since the college was to serve as its own advertisement. Moreover, as he wrote to one of his academic advisers: ‘I propose that the “Ladies University” at Egham, should be of its kind a grand imposing building that it may not by an insignificant style dishonour its name. – You are aware that nowadays, it is necessary to fill the eye.’ For that reason, Holloway felt the necessity to visit the larger colleges to make his own judgement and for Crossland to draw up a design. However, the trip ended with the illness of Holloway, which allowed Crossland to persuade his client to return to Renaissance style as Holloway lost his interest in Oxbridge style.

‘I know nothing, or next to nothing’

Despite Holloway’s preoccupation with and his major involvement into planning the college, he had little knowledge of academic life. As he said: ‘I know nothing, or next to nothing’. Therefore, he understood he needed advice and asked his friend James Beal, a journalist, land agent and reformer, to arrange a meeting with educationalists and politicians who would advise him. At the meeting, Holloway honestly admitted his lack of relevant knowledge but he insisted that the College had to be a university, not a high school or a teacher training college, as it was advised to him. His plan to build a university for women attracted a lot of attention since women’s education was a widely discussed topic with Girton and Newham Colleges in Cambridge being established in the second half of the nineteenth century. Having become a well-known manufacturer by that time he started advertising his institutions by sending notices to newspapers all over the world, which attracted even more attention to him and his institutions.

Personal Tragedies

The construction and planning of the institutions suddenly stopped because of the death of Holloway’s beloved wife, Jane, who died suddenly from bronchitis on September 26th 1875. Jane had been his constant support for nearly four decades and Thomas Holloway never really recovered from the devastation caused by her demise. He remained in deep morning for several weeks, ignoring his business affairs and the development of the institutions. In a tragic parallel, four months after Jane Holloway’s death, Crossland’s own wife, Lavinia, died. Despite the fact that those tragical events considerably slowed the construction of the institutions, the work had to continue. Holloway drafted the Foundation Deed for the College, which was called Holloway College, and had to provide the best education for women of the middle and upper classes. The Foundation Deed was executed on 11 October 1883 and formalized Holloway’s wishes regarding his institution. One of the aspects Holloway specified was that the college was to be non-denominational but it should be run as an orderly Christian household. Holloway’s main desire was that his college should be able to confer degrees. Holloway also stated that the college should be built as a memorial to his wife whom he credited for the inspiration, saying ‘The College is founded by the advice and counsel of the Founder’s dear wife, now deceased’. Because of the lack of energy and the feeling of his imminent death Holloway appointed trustees for his college: George Martin (husband of Jane Holloway’s youngest sister), Henry Driver (younger brother of Jane Holloway) and accountant, politician and Member of Parliament, David Chadwick. Before the construction of the college began there was a delay of 3 years for which the reason is not known. However, when the building finally started, Thomas Holloway could not come to the site due to his deteriorated health. The first brick was laid by George Martin on 12 September 1979, and from there on the construction progressed quickly. The building was completed in four years although there was a delay of around three years in opening the college.

‘He, being dead, yet speaketh’

Thomas Holloway’s lack of enthusiasm caused by his wife’s death and his deteriorated health made him delegate day-to-day supervision of the College to Crossland and the overall control to George Martin. When having made George Martin and Henry Driver responsible for the completion of the project by naming them trustees, he also required them to add the name of Holloway to their surnames. It is known that he only visited the college building site four times. On his third visit to the College, Holloway praised Crossland saying: ‘Well done, Mr Crossland, I am more than pleased’. Crossland had a good relationship with Holloway and admitted to learn useful business skills from him, saying: ‘The late Mr Holloway was a client who sent me to school, a man who (quoting Holloway’s own words) ‘always worked with his head, never with his heart.’’

Holloway did not live to see the opening of the college nor did he witness his biggest wish for college to confer degrees come true. On the Boxing Day in 1883 at the age of eighty-three, Thomas Holloway died of congestion of the lungs. Crossland designed a tomb for the Holloways with the epithet that read ‘He, being dead, yet speaketh’. He speaks through the legacy he left and this speech is loud.

Holloway’s College was a fine architectural building, as well as serving as a one of a few institutions providing high education for women. Holloway’s intention was not only to build a modest college but to make it the finest and grandest architectural masterpieces. When the building of the college was yet to be started, Crossland was assigned to provide Mr Beal with the details of this new project about which the architect had to say that ‘the founder intends that there shall be nothing like it in Europe’.

Indeed, the College was one of a few buildings of such high quality erected in the late nineteenth century and one of the largest constructions in Britain in 1880s. The grandeur of the College impressed also because it was built for 250 women students while Cambridge and Oxford had only accepted a little number of female students. The architectural style of the College was also ground-breaking as it was drawing on different sources, combining style elements from various times and places. The eclectic style achieved by Crossland was precisely what the architects of that time were looking for: a Victorian style. Holloway’s liberal religious views, and his intention for the chapel of the College to be non-denominational were reflected in the decoration that includes the carved heads of Mohammed and Confucius as well as biblical figures. A great consideration was also given to health and safety of female students. The architect based the interior design on corridors, which was different from the arrangement of rooms in the existing universities for men and was more secure for the community of females. The consideration that was given to all the details turned the College into one of the most prestigious universities in England.

The Completion of the Institutions

The Sanatorium building was completed during 1882. To celebrate this, the Illustrated London News published an engraving of the Sanatorium at the beginning of January 1884.

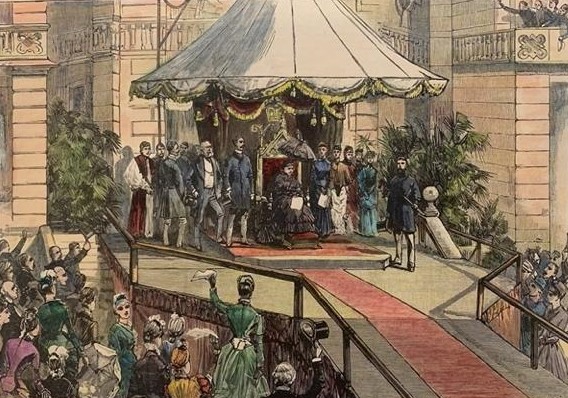

However, the Commissioners in Lunacy rejected the license because of the new regulations which the Sanatorium did not comply with. Subsequent changes were made and the Commissioners in Lunacy finally officially licensed the Holloway Sanatorium on 12 June 1885. It was formally opened on 15 June by Edward, Prince of Wales with the Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra). There was a special ceremony at which George Martin-Holloway hosted the Royal party and Crossland was presented to the Prince. In 1948 the Sanatorium was taken over by National Health Service and closed in 1981. It was deteriorating until 1995 when a development company was permitted to develop the grounds with the restoration of the main structure. The main building was converted to town houses. High-class housing was built in the grounds and the site became Virginia Park.

The College was substantially completed by the end of 1883. The College was officially opened on Wednesday 30th June 1886. Queen Victoria visited the opening ceremony and allowed the College to adopt the title ‘Royal’ in her honour.

This was a special day in the history of Egham as it attracted a lot of visitors coming from neighbouring towns Windsor, Staines, and Chertsey, and even from London to look at the ground-breaking women’s college. Moreover, the College was opened by the most important female figure in the country which made the city extremely proud of the Royal Holloway College and the city’s increasing reputation. To this day, Royal Holloway University attracts a lot of visitors from all over the world.

- Anthony Harrison-Barbet, Thomas Holloway, Victorian Philanthropist: A biographical essay (Lyfrow Trelyspen, Gorran, St. Austell, Cornwall, 1990) p. 1.

- Bingham, Caroline, ‘The Founder and the Founding of Royal Holloway College’ in ed. by Moreton Moore Centenary Lectures, 1886-1986 (Egham: The College, 1988), p.15.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p.1.

- Binns, Sheila, W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2020).

- Bingham, 1988.

- Binns, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Blythman, Guy, The Holloway Sanatorium, (Egham, 2014), p. 7.

- Binns, p.138.

- Williams, Richard, Thomas Holloway’s College: The First 125 Years (Egham, 2012), p. 7.

- Binns, 2020.

- Quoted in Saint, Andrew and Richard Holder, ‘Holloway Sanatorium: A Conversation Nightmare’, The Victorian Society Annual, 1993, p. 25, citing the Ashbee Journals.

- Binns, Sheila, W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2020), p. 144.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (R.I.B.A.) was formed in 1834 as the Institute of British Architects in London and later was granted with a royal charter. It was founded with a purpose of the advancement of architecture and the promotion of architectural education in the United Kingdom.

- Ibid, p. 158.

- Ibid, p. 175.

- Binns, 2020.

- Ibid, p. 153.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Binns, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Bingham, Caroline, ‘The Founder and the Founding of Royal Holloway College’ in ed. by Moreton Moore Centenary Lectures, 1886-1986 (Egham: The College, 1988), p.17.

- Binns, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Binns, 2020.

- Binns, p.187.

- Ibid, p.187.

- Ibid.

- Harrison-Barbet, p.27.

- Binns, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.