Victorian Children’s Literature and the Invention of Childhood

In this article, Alice Castle looks at one of the sets of objects from our Victorian handling collection (available for loan, free of charge, for local schools).

In this article, Alice Castle looks at one of the sets of objects from our Victorian handling collection (available for loan, free of charge, for local schools).

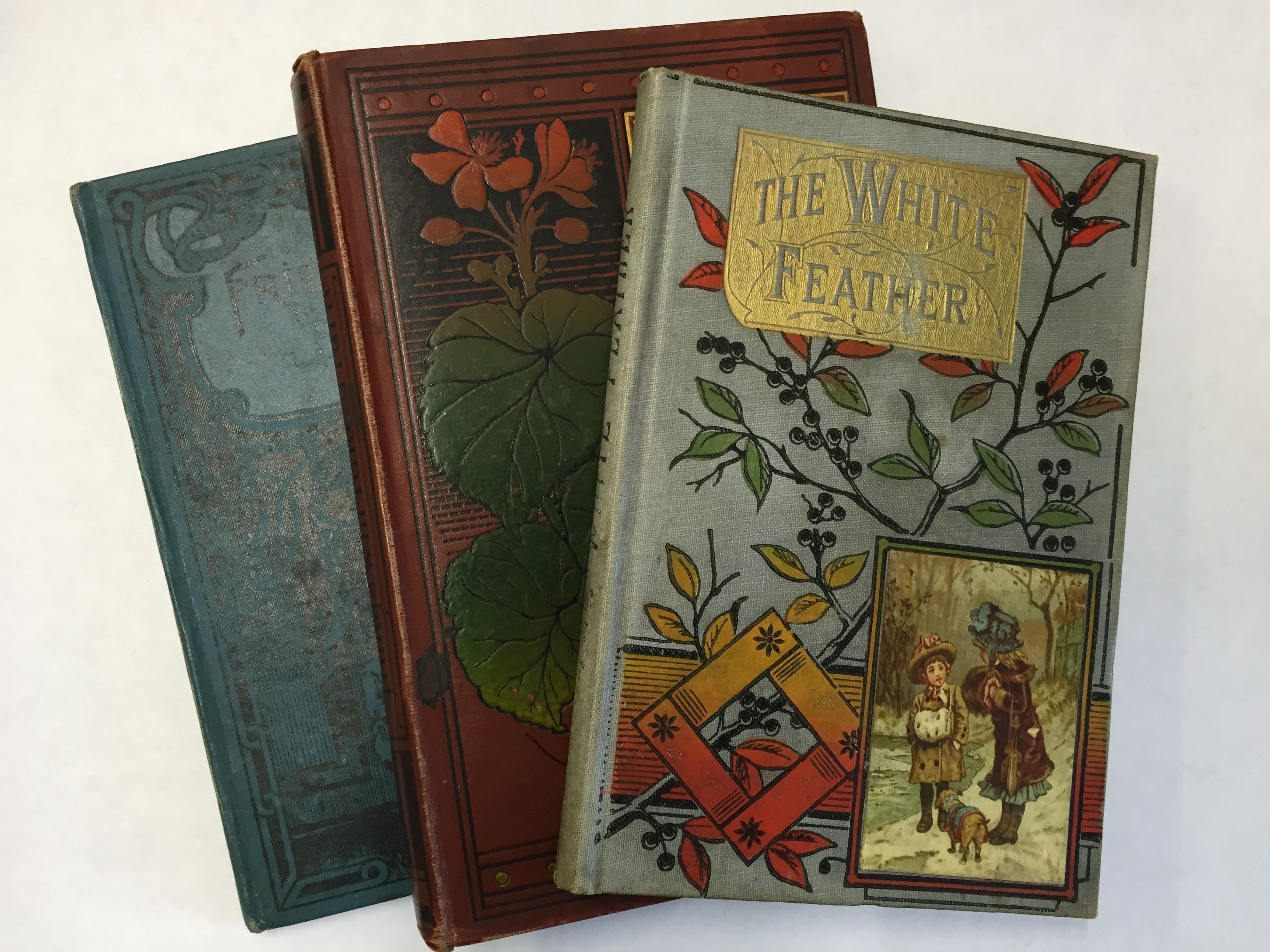

The three books under discussion are ‘The White Feather’ (or Small Beginnings and Sad Ends,) published somewhere between 1860-1878 by The Religious Tract Society, ‘Things will take a Turn’ by Beatrice Harraden, published in 1898, and ‘Friend and Foe’ (or The Breastplate of Righteousness) published in 1880. All three books have a moral and religious overtone to them and show the significance of the emergence of children’s literature in the Victorian period.

This was a time when childhood was being formed into a time of innocence and freedom and there was a move away from the previous Puritan belief that all humans are born with sin. The turning point of this change was the work of the philosopher Rousseau in Emile, published in 1762, which rejects the doctrine of Original Sin and argues that children are innocent until they are corrupted by later experiences. Previously children’s literature had been predominantly focused on saving children through instructing them, but during the Victorian period this included moral tales that taught values intrinsic to the Victorian Middle Class, such as hard work and honesty, through narratives that allowed the children to be able to learn from them.

Authors up until the 20th century celebrated this new concept of childhood. These books were published by groups such as the Religious Tract Society, a British publisher that produced Christian literature aimed predominantly at children, women and the poor. However, the ‘invention of childhood’ can be seen to have been limited to the middle classes and above. Working class children were instead often forced into work from a young age, the average age being 10 years old, to provide towards their household’s income.

Due to the rapid industrialisation of Britain throughout the nineteenth century there were increased work opportunities for children, as they provided cheap labour. However, the work on offer was usually dirty and dangerous in factories as scavengers or in the mines picking out coal. This means that working children’s childhoods were cut short due to the financial needs of their families. Also, as previously mentioned, where much of the children’s literature produced depicted middle class values they were aimed at a particular audience and would have thus left out the interests or experiences of the working class. However, ragged schools were available for children too poor to receive an education elsewhere. Charles Dickens, amongst others, had fears concerning the uneducated masses in a rapidly developing country and Empire. These schools were set up as charitable organisations and provided children with food, clothing and lodging also. There was an emphasis on reading, writing and studying of the Bible. This shows that some working class children were given the opportunity to receive an education and better their chances in society. However, on the whole working class children had fewer chances of receiving an education than those of the middle class, and this is reflected in the children’s literature of the time and the values they put forward.

Alice Castle is studying History at Royal Holloway, University of London.