Women: Wives, Workers & War Part 1

Introduction & Acknowledgements

The Egham Museum’s previous exhibition Suffrage in Egham, explored the roles of women and their fight locally and nationally for the right to vote. However, 2018 not only marked the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, which gave some women the right to vote, but it was also the anniversary of another major event; the end of the Great War.

This exhibition explores these women, their jobs and their expectations, including what happened after the war. Egham Museum is interested to hear of any stories you may have that can to contribute to this exhibition, for example, did you have a female relative that was employed during 1914-18 in the local area? Please share your stories with us.

This exhibition is possible thanks to a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, support from the Englefield Green Memorial Trust and with special thanks to the work of Egham Museum volunteers:

Chiara Artale

Angela Mascolo

Geoff Meddelton

Felix O’Kelly

Margaret Stewart

The Lead up to War

In the years before World War One, there were great power rivalries in Europe. Increasing concerns over countries developing military forces large enough to attack empires and imperialism, created mistrust and anxiety. In response, countries formed alliances to help keep this power in balance. There were two key alliances: in 1882 Germany, Austro-Hungary and Italy formed the Triple Alliance; Britain, France and Russia created the Triple Entente in 1907.

In 1908, Austria annexed the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Ottomans. Serbia objected to this and secured Russian backing, while Germany backed Austria. Tensions between Serbia and Austro-Hungary by this time, were precarious. So when, on 28th June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, visited occupied Bosnia on what was Serbia’s National Day, it was seen as a direct insult to the Serbs. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Bosnian-Serb, Gavrilo Princip who claimed to be acting on behalf of Serbian nationalism in attempting to liberate Bosnia away from Austro-Hungary. Austria, supported by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, accused Serbia of planning the assassination and begins preparing for war. Serbia contacted its ally Russia, who also asked France for support. The two great empiric alliances were precariously poised for war.

Britain was not required by any treaty to support France or Russia in the event with war Germany. In fact, many British politicians were against intervention, and so no action was taken when Austria declared war on Serbia on 28th July 1914. Many felt that another war on the continent at this time would be fought in the traditional style; that of the cavalry acting as scouts, artillery shelling fortified positions and infantry fighting the main battles with rifles, believing it would be finished within a few months. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, war was often seen to define nations and was deemed necessary; sometimes even glorious.

The Reaction to War

On 31st July 1914, the International Women Suffrage Alliance (IWSA), founded in 1902, circulated its International Manifesto of Woman to the Foreign Officer. Among those who signed was Millicent Garret Fawcett, the President of the National Union of Women’s suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

We, the women of the world, view with apprehension and dismay the present situation in Europe… In this terrible hour, when the fate of Europe depends on decisions which women have no power to shape we, realizing our responsibilities as the mothers of the race, cannot stand passive by. We […] appeal to you to leave untried no method of conciliation or arbitration for arranging international differences to avert deluging half the civilized world in blood.

Russia and France had mobilised their troops for war by 31st July and when Tsar Nicholas II refused to stand down, Germany and Austria declared war on Russia. Britain was still not officially at war with any country at this point. It wasn’t until German troops invaded Belgium (because they refused them entry in order to attack France as part of The Schlieffen Plan), that Britain was obligated by the Treaty of London, dating back to 1839, to protect Belgium’s sovereignty.

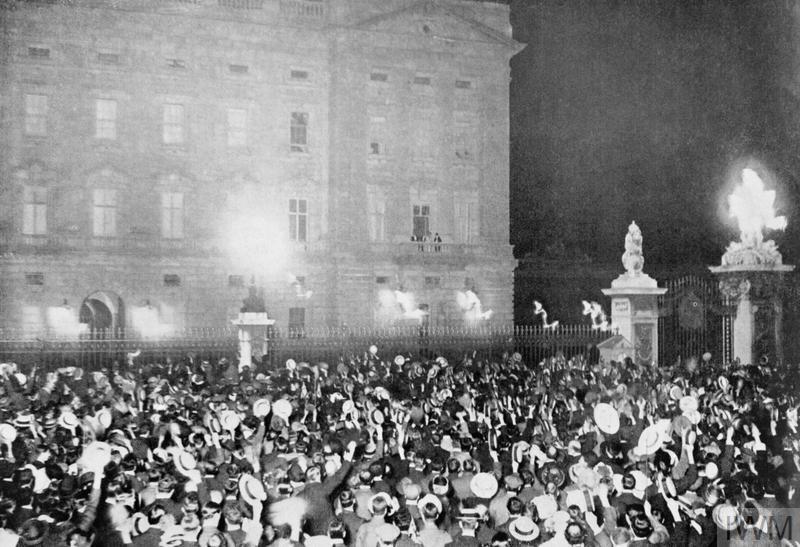

When the announcement came that Britain had officially entered into war at 11pm on 4th August 1914, it was received with great enthusiasm by many but there was also caution and the reality of what was to come:

The situation is absolutely unparalleled in the history of the world. Never before has the war strength of each individual nation been of such great extent, even though all the nations of Europe, the dominant continent, have been armed before. Attack is possible by earth, water & air, & the destruction attainable by the modern war machines used by the armies is unthinkable & past imagination.

Vera Brittain’s War Diary, 4th August 1914.

The War and Suffrage

The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) continued campaigning for equality throughout the war. President of the NUWSS, Millicent Garret Fawcett, appealed to members to join the war effort as a means of proving themselves worthy of the vote, although had been in favour of a peaceful solution to the crisis in Europe. She wrote in the suffrage magazine, ‘The Common Cause’ on 7th August 1914, “Let us show ourselves worthy of citizenship, whether our claim be recognised or not…”

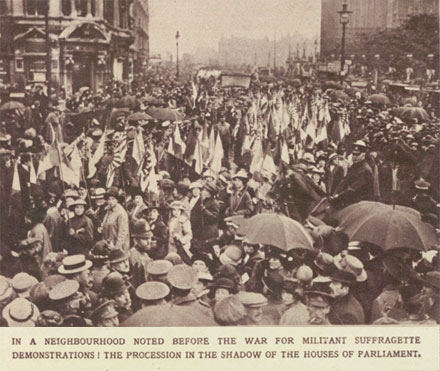

The attention of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) shifted away from their political aims and was channelled in to supporting the war effort. Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst declared a truce so the Government declared amnesty and on 10th August, all suffragettes in prison at the outbreak of war were unconditionally released. Mrs Pankhurst was fiercely patriotic and as far as she was concerned, there was no point in having the vote without a country to vote in. She devoted her time to encouraging women to join the war effort, but soon discovered that some trade unions were refusing to accept them in what they considered to be ‘men’s jobs’. This led Mrs Pankhurst to leading a vigorous campaign for the ‘right to serve’. On 17th July 1915 the Women’s Right to Serve Demonstration in central London attracted around 30,000 women, despite the bad weather.

Sylvia Pankhurst, unlike her mother Emmeline and sister Christabel, was a socialist and a pacifist stating in her memoirs, ‘The Home Front’, “Stop this breaking of homes, these sad privations, this mangling of men, this making of widows!” After her expulsion from the WSPU, Sylvia founded the East London Federation of Suffragettes in 1914, an organisation that saw the vote as just one aspect of the struggle for equality alongside fighting for a living wage, decent housing, and equal pay, and much more. Sylvia continued to campaign against the war and in 1915, gave her enthusiastic support to the International Women’s Peace Congress held at The Hague, despite being unable to attend.

The War Ends

On 6th February 1918 some women were granted the right to vote due to the Representation of the People Act becoming law. At the time, many people believed that role women played during the war had helped advance them politically and economically. Mrs Millicent Fawcett said in 1918 that the war revolutionised the industrial position of women – it found them serfs and left them free.

The Act saw the electorate add 8.5 million new female voters. The following November Parliamentary Qualification of Women Act also allowed women to sit in the House of Commons and in December 1919, Nancy Astor was elected as the MP for Plymouth Sutton. And so, on Saturday 14th December 1918, women over 30 who met a property qualification, first took to the polling booth and voted for the first time.

For those who qualified, it was a significant step, as one woman recalled:

When we got the vote – and I admired Mrs Pankhurst – I said, ‘I’ll never neglect to vote.’ I always voted. The war allowed women to stand on their own feet. It was a turning point. Men became a little bit humbler. They weren’t the bosses any more.

Jane Cox, IWM interview.

In reality, for many women, their lives went back to their pre-war state as contracts of employment during World War One had been based on collective agreements between trade unions and employers which stated that women would only be employed ‘for the duration of the war’. Mary Rumney, a former society girl who was a nurse during the war, was quite sorry when the was over. I was going back to the leisured classes. (IWM interview.) Acceptance wasn’t easy for the women who had experienced a new kind of work during the war:

It was very difficult if you had been a WAAC. We weren’t looked upon with favour by the people at home. We had done something that was outrageous for women to do.

Ruby Ord, IWM interview.

Read part two of Women: Wives, Workers, War here.

To find out more about the impact of war in our area, visit http://www.memoriesofwar.eghammuseum.org