Egham and the Empire: Tea, Tobacco and Trade

‘In the late nineteenth and well into the twentieth century, the empire was a frequent backdrop for commercial advertising. Advertisements for soap, chocolate and many other commodities invoked the Empire’

Philippa Levine, The British Empire : Sunrise to Sunset, p.105

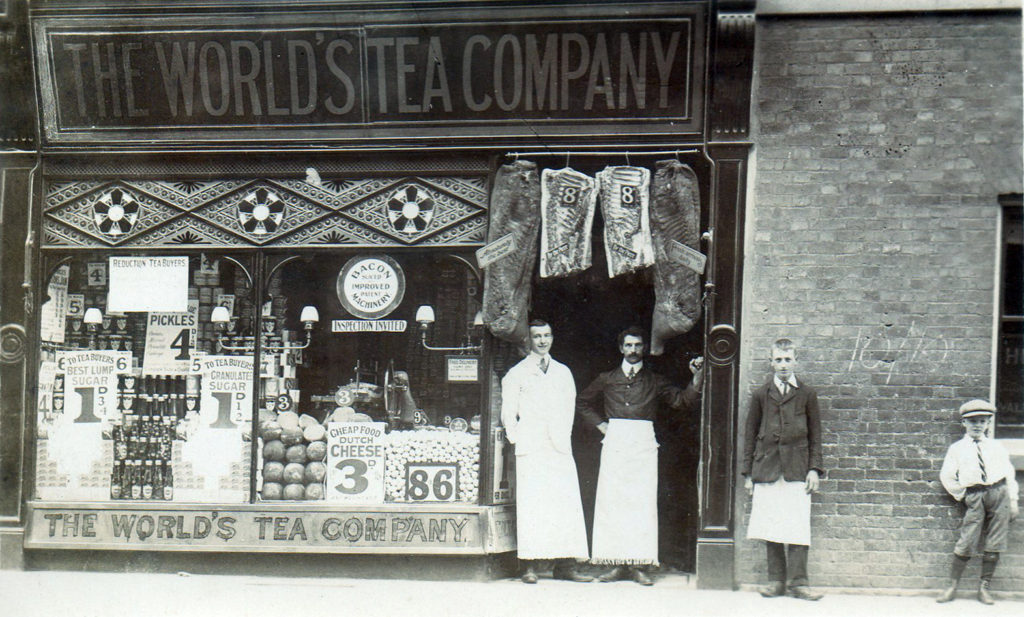

One of the main ways in which people came into contact with the Empire was through foodstuffs directly imported to Britain from the Empire. Our photograph of ‘The World’s Tea Company’ [1] a shop at 82 Egham High Street during the turn of the century, demonstrates the range of food on offer to the community of Egham that came from both imperial and non-imperial territories.

In the 1660s, King Charles I had married Catherine of Braganza, who helped to make tea popular in Britain amongst the upper classes. Due to the increased demand for tea leaves, the East India Company, which had been founded in 1600, helped to ship vast quantities of tea to Britain from Asia. For many centuries, the majority of tea leaves brought back to Britain were grown in China. Our painting by John Hassell [2] depicts Clarence Lodge, a house that stood on Middle Hill, Englefield Green. In the mid nineteenth century, Richard Torin occupied the house. Torin was a member of the East India Company and often spent large periods of time working in India.

By the nineteenth century the consumption of tea had become popular across the class system. The working class were encouraged to drink this beverage, as it was seen as a more acceptable than the drinking of alcohol, which grew increasingly unfashionable as a result of the temperance movement that had first emerged in the 1830s. The consumption of tea had also led to an increased production in tea related goods, such as ornate teacups and teaspoons. This cannister [3] was most likely used to store tea in. A small clue to its use is in its decoration, as if you look closely you can see that tea leaves have been carved into the wood. Interestingly, the small hole in the front of the caddy is where a small lock would have been, locking the tea leaves safely away from potential thieves!

Brands such as Mazawattee Tea Company and Lipton’s were staples of the late Victorian and Edwardian High Street. Mazawattee’s advertising campaigns were extravagant, with one stunt even involving a carriage pulled by zebras! Their tea was produced in Ceylon, now modern-day Sri Lanka, which came under the possession of the British in the early nineteenth century and was used as an alternative to tea imported from China.

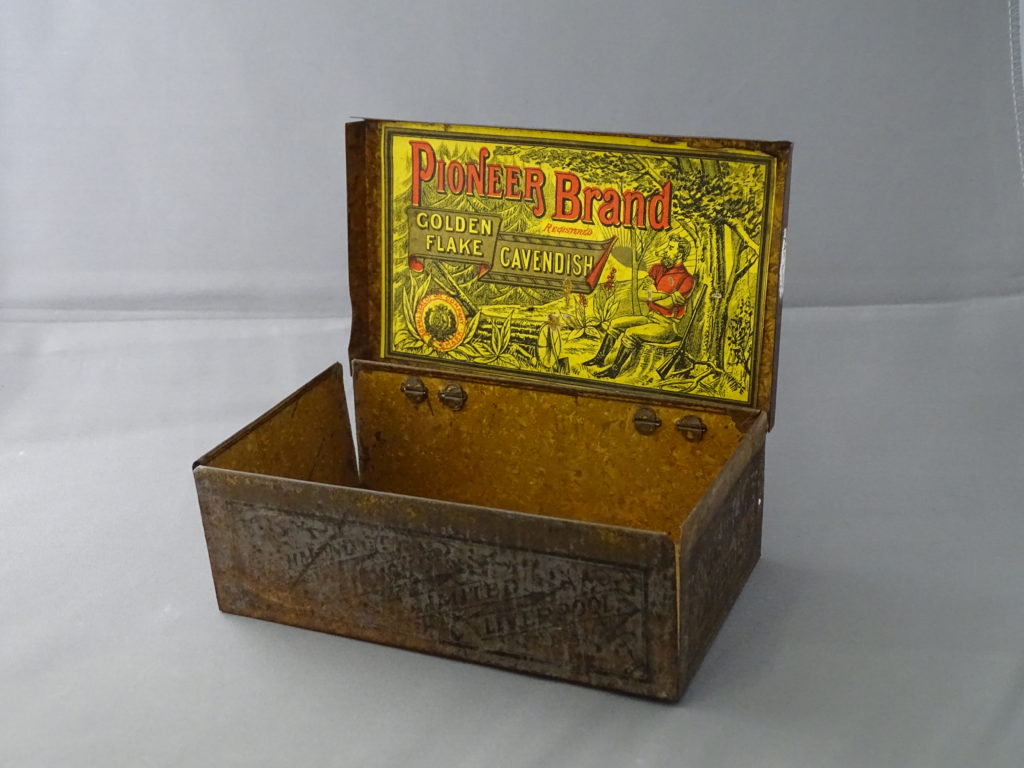

Many companies invoked the concept of the empire in their advertising campaigns, as the appeal of the exotic was popular with consumers as it helped to create escapism as well as bringing the empire to the British High Street. Many companies invoked empire in their advertising, as the exotic appeal was popular with consumers. This Pioneer Tobacco Tin [4], uses the idea of the brave and adventurous individual exploring unknown territories to appeal to consumers, linking to the idea of conquest and settlement.

Back in Egham, this Mazawattee advertisement plaque [5] was at one time displayed at 57 High Street, which during 1887- 1984 served as a grocery shop and was owned by various families over the years. The Mazawattee Tea Company was well-known throughout Britain and its advertising campaign could be found in many towns and cities. Although at the time they were known for their tea products, by the early twentieth century they had also begun to produce chocolate. Our small chocolate Mazawattee tin [6], produced for the coronation of Edward VIII in 1902, highlights the links between imperial brands and patriotism. The company had begun to vary their products as a result of an increase in tax duty, and it has been suggested by historians that the cost of the Boer War was to blame for the rise in duty.

Although the company ceased trading in the mid-twentieth century, the brand was later revived and can still be purchased today [7]. Many products and brands have links to imperial histories, and serve as proof that in some ways, the consequences of empire are still with us.

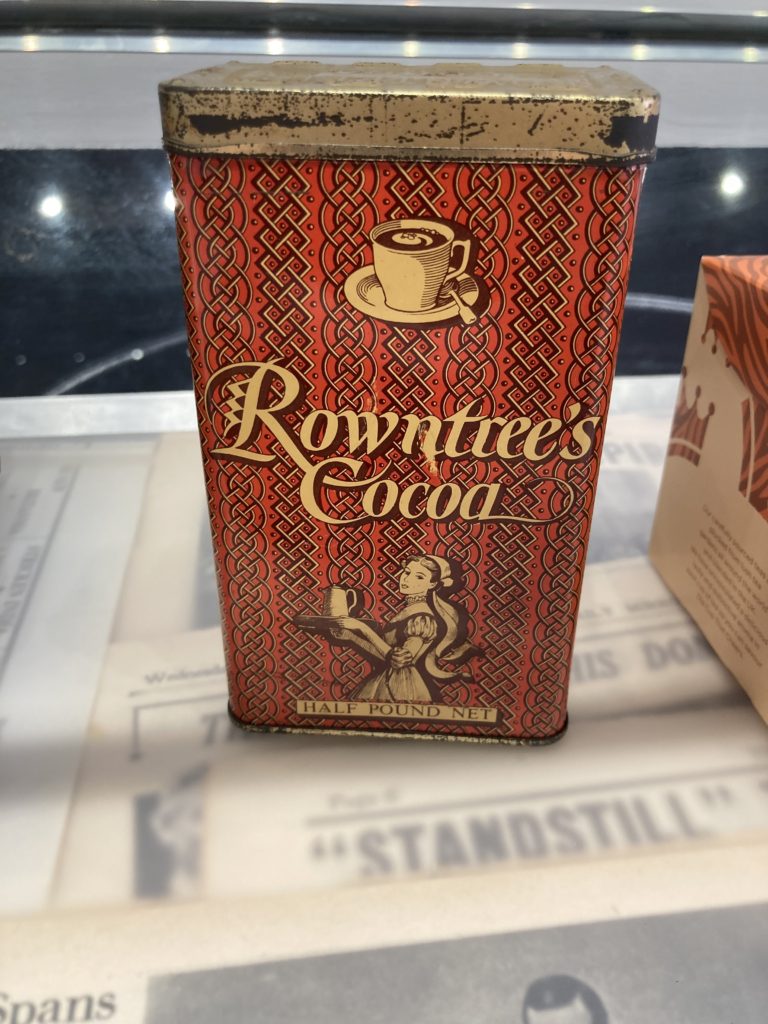

Interestingly, not all of our now famous brands actively linked their work to colonial profit and exploitation within the empire. Joseph Rowntree, a partner in the world-famous Rowntree company, deplored colonial conquest and the exploitation of workers. However, recent historical investigation by The Rowntree Company has found that it did benefit from indentured labour and purchased goods (for the making of cocoa) from workers enslaved by other European powers, in some cases as late as the early 1900s. This demonstrates that in Britain, the empire was a constant presence across the metropole, but the relationship between brands and empire is not always clear [8].