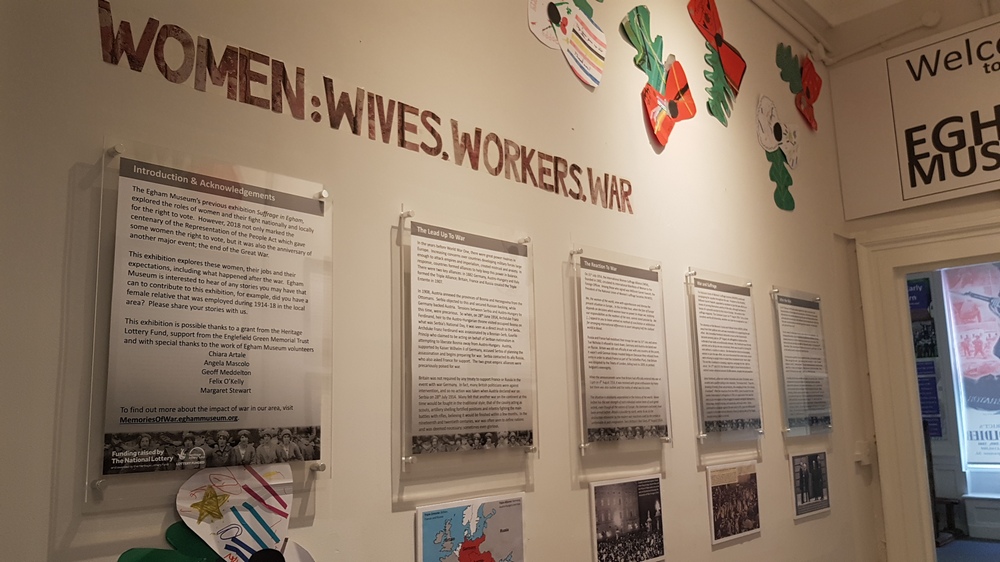

Women: Wives, Workers & War Part 2

Read part one of Women: Wives, Workers and War here.

Pre-war Life for Women

Before the Great War, the reality of nineteenth and early twentieth century women was one of oppression and extremely limited freedom, no matter her station. Women were expected to be demure, passive and obedient to their husbands and other men in society. In legal terms, once a woman was married, she ceased to exist in the eyes of the law and her whole identity was consumed by her husband. Even before marriage, women were under the legal control of her male relatives.

Middle and upper-class women were expected to care for the children and the home. Women did have some engagement with the public sphere, but it was minimal. Philanthropy and charity was a common activity for middle and upper-class women and was actively encouraged. This could be called a freedom with limitation as they are active in society but still practice feminine ideals, such as being maternal. Engaging in politics was even less common; the extent of women’s participation was accompanying their husbands when they went to vote.

Female employment for working-class women in the 1850-70s appears to have been higher than any recorded, until after World War Two. Around 30-40 % of women from working class families contributed significantly to household incomes in the mid-Victorian years.

The largest employment for a working-class woman was in domestic service such as maids, cooks, or nurses living in their employers’ house. In 1911 there were approximately 1,400,000 (out of a female population of 15 million) women in private domestic service. Many young women went into service as soon as they left school and would not work in a large stately house. Instead, they might be the only servant in a middle-class town house. For these women, their jobs tended to mean working long days for very low pay, obeying strict rules, with little time off.

Outbreak of War

At the outbreak of war, Britain’s armed forces were caught relatively unprepared as the British Regular Army totalled only 250,000. So, on 8th August, the War Secretary Lord Kitchener launched his appeal for male volunteers. The now infamous “Your Country Needs You” poster of Kitchener himself, with his recognisable bushy moustache and outstretched index finger pointing at the potential recruit, initially encouraged up to 30,000 volunteers a day.

Soon these numbers began to dwindle, and so recruitment became the main focus of propaganda for the next two years until conscription for men was introduced in January 1916. The horrific tales brought back by the wounded from the front line not surprisingly, discouraged many men from signing up, and it seemed Kitchener’s appeal alone was not enough to compete with such a frightening reality of war.

Portrayal of Women

In war propaganda, nations were often personified by women, such as Britannia; our mother country, the place of one’s birth, the place of one’s ancestors. “Brave Little Belgium” was also often symbolised by a woman being trampled by German soldiers.

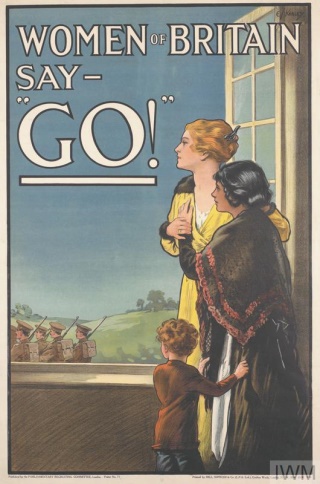

Women soon began to appear in recruitment posters aimed at men. E.V Kealey’s painting for the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee, “Women of Britain Say –‘Go!’”, from May 1915, clearly sends the message to women that they should encourage their sons, husbands, brothers, and sweethearts, to join the war effort as it is their duty. Not only is it telling women that they can play their part in this war by being strong but also despite their fears, they must encourage their men to go to war. The poster also lets the men, who have not yet volunteered, know that the women in their lives want them to ‘Go!’. The poster depicts one such brave woman, looking on as her men march away – she is a pillar of strength to the young girl and boy beside her. Essentially, this is a recruitment poster for the subscription of men, but it had become clear that the cooperation of women would be essential in winning the war.

Call to Women

As men were sent away to fight in the war, there was a shortage of labour on the home front. Women took on jobs in shops, on buses, in the Police force, and in the fields, to fill a number of positions previously occupied by men. Women soon became the target of governmental recruitment propaganda, and those who might previously have been enticed into domestic service, were being drawn away by alternative employment to satisfy the demands of war.

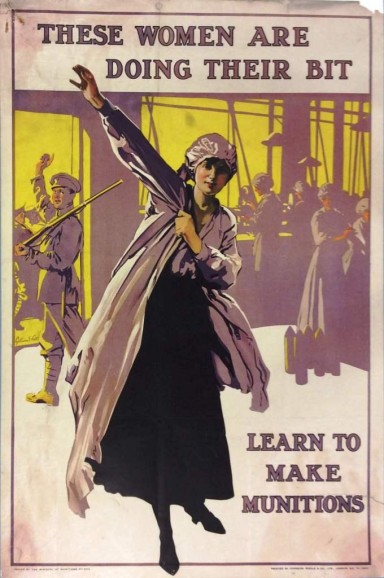

The poster “These Women Are Doing Their Bit” from 1916 shows a woman putting on the protective overalls of a munitions worker. There was initial resistance to women in munitions as this was seen as ‘men’s work’. But when conscription was introduced in 1916 for men, it meant women were necessary in order for there to be enough munitions. By 1917 these factories, mainly employing women, produced 80% of weapons and shells used by the British army.

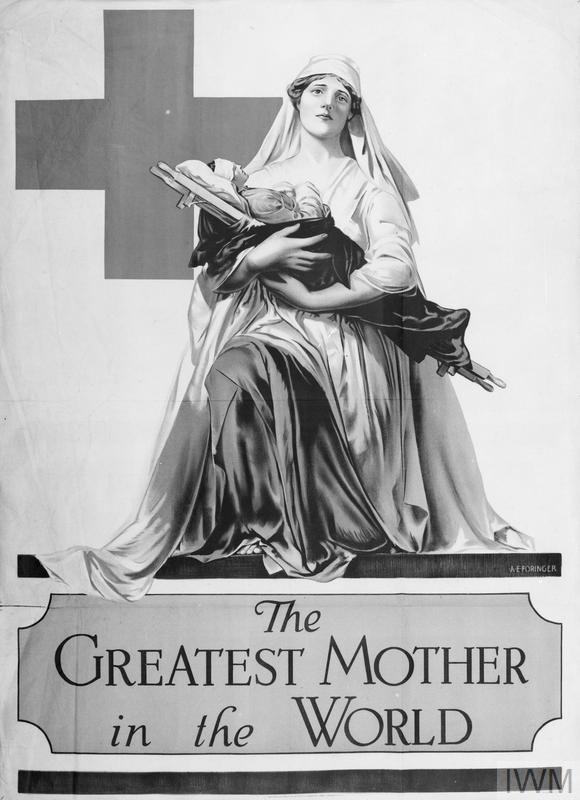

For the middle and upper class women, who had very few career options, the temptation of actually working to help the country appealed greatly. Many were lured into nursing by posters such as “The Greatest Mother in the World”. This 1918 poster by Alonzo Earl Foringer for the British Red Cross tries to appeal to a woman’s ‘natural instinct’. Women are traditionally portrayed as nurturers with motherly instincts and here, the saintly Madonna figure seated is ‘the greatest mother in the world’. Robed and veiled with the Red Cross sign on her hat and gazing towards heaven, she cradles a wounded soldier in a stretcher.

To find out more about the impact of war in our area, visit http://www.memoriesofwar.eghammuseum.org